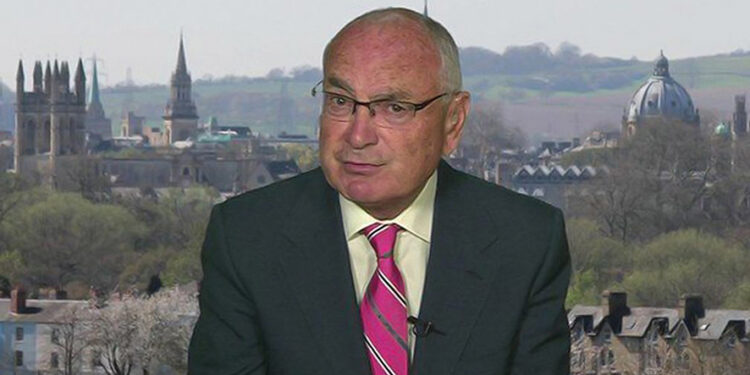

When my grandchildren reach adulthood, I fear they will either be under Russian rule or in a war against it, – Professor Anthony Glees, director of the Center for Security and Intelligence Studies (BUCSIS) at the University of Buckingham, issues a stark warning about Europe’s future. In an interview for Radio Free Europe’s Georgian Service, he analyzes the new U.S. security strategy, Europe’s faltering defense posture, Germany’s political dilemmas, and Ukraine’s increasingly perilous position.

After the release of the US National Security strategy and the subsequent speech by Defense Secretary Hegseth, many have heralded it as an official declaration of an end to the unipolar world order – is that so?

Well, I think it’s a more complicated paper than that kind of binary interpretation allows. What President Trump is saying is that by 2027 Europe needs to take the lead in its own defense, and that although the United States will be there in the background, by 2027, which is not far away, European security has got to be a European project, not an American project. And there are many people who rather agree with that view. And you know, it is unfortunate, perhaps, that that is the way the world is.

We have got very used, ever since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the “end of history” attitudes that gripped us all, particularly in Western Europe, of not worrying too much about spending money on defense, because we wanted to develop social policy and give the money away in welfare. And once you start doing that, as UK politics shows right now, you can’t stop doing it. So it’s a very, very dangerous position.

The bottom line is, yes, we need to spend much more money on our defense, and we need to do the things that allow our defense to look credible, and that’s not just about hardware, and it’s not just about intelligence: it’s also about the political will to defend our continent from Putin’s aggression. So the document in that regard chimes with what I think is the correct view. Where the document is wrong, in my view, is to suggest that the aims of Putin’s Russia and the aims of Trump’s America are the same and should be the same.

Notably, Moscow also said that the visions align, which was probably something nobody would have expected in decades past.

Yes, and I think many Americans and many Republicans will, as time goes by, find that unacceptable, because, as everybody knows, Putin’s regime is a regime of kleptocrats and oligarchs and has no sense of human dignity or human rights, or indeed respect for human life. Americans do not want to be aligned with those sorts of attitudes. Yes, they want to make money, they want to give everybody a chance, but on the whole, they don’t like the sort of things that Putin has to do in order to stay in power.

Where I think the security strategy is dangerously confused, however, is on the one hand saying yes, Europe must man up, must take much more control of its own security and defense, and cannot rely on the United States of America except as a possible backstop, and on the other hand, where the document says it wants to have “conservative governments” running Europe and opposition to the European Union. That is based on a complete misreading of the actual necessity. If you want a stronger European defense presence, as the President says he wants, then you also need to have a much stronger European political identity, which the President says he doesn’t want- he says he will support parties who are actively supporting him.

My strong suspicion is that these contradictions are to be laid at the door of Nigel Farage, who sees himself as the next British prime minister, and who is, on the one hand, obsessed by and consumed with a hatred for the European Union, but on the other understands, I think, that the EU could be a very powerful player between the United States and Russia. Farage and his friends may have been whispering into the ears of the State Department and the Oval Office that Europe needs to take the burden of defending itself off American shoulders, while also supporting politicians who believe in a weaker European Union.

That simply doesn’t work; it doesn’t hack it. That is the message Germans and the French in particular will need to put to the State Department and to President Trump. And he’s mercurial — he’s not just a Midas, he’s also a Mercury, he’s Quicksilver. He’s not just gold. He holds a number of views that can’t easily be amalgamated. In many respects, they’re contradictory and confusing, yet they chime with what Trump calls “common sense.”

On that mercurial nature—how likely is this new document to endure? Will we actually see it enforced, or should it be viewed more as a wishlist of how the world or the US ought to work, according to people like Elbridge Colby and others?

I can see no sign that it will not become policy. I can see no sign that the Democrats will be able to win the next presidential election and turn policy around. And the people I have spoken to who are in the governmental world are all working on the basis that the next President of the United States will be JD Vance, whose own policies mirror those put into that document. This is a new MAGA America. It’s a 21st-century phenomenon in many ways. Yes, it harks back, it strikes chords. The more you know about American history in the 19th century, the more you can see that Trump speaks to tropes deeply embedded in American history. But the world in which Trump operates is very different from the 19th century, from the world where all the great powers tried to maintain peace — they failed, of course, with the First World War, but they tried. Now, particularly with Russia but also with China, you have revisionist regimes that are very different and very actively seeking conflict and confrontation.

Will Europe realistically be able to defend itself on its own by 2027?

Well, I think it is feasible, definitely. It is feasible if we want to do it. At a micro level, you could do it. In the UK, the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s golden rules could be changed to allow more borrowing. After all, defense spending is actually quite good for a country’s economy in all sorts of ways — it boosts jobs and all these things. They could borrow more.

In 1940, during the Second World War, Britain borrowed vast amounts of money in order to ensure that it was armed, in order to defend itself against German aggression. The way it’s being presented at the moment is a sort of welfare-versus-defense dichotomy, and that there’s no money, nobody in Britain has any money, etc. I don’t think that’s true. I think there’s a big black economy. There’s a lot of money in this country. So we can afford to pay for more defense without necessarily giving up the National Health Service. If we don’t want to give up the National Health Service, we can borrow. We can take out a loan from America, for example, in order to do this.

You’ve written a book about Germany reinventing itself – will it have to do it once more? Is it ready to? Does it want to?

The German situation is complex, and not just due to reunification. The far-right threat mainly comes from eastern Germany, highlighting a systemic problem the country must address.

Then there are the serious errors made by Angela Merkel as chancellor, which Germany is still grappling with today. Chief among them was her inexplicable decision to phase out nuclear energy. Despite her scientific training, she acted unscientifically. If she feared a Fukushima-style disaster, she would know that most winds in Germany blow from the west, and France has numerous nuclear plants—so contamination would have been likely regardless. The decision was political, aimed at appealing to environmental voters, but it left Germany dependent on Russian oil and gas. It was a profoundly misguided move.

Another major blunder, which I criticized at the time, was taking in over a million migrants in 2015 about whom Merkel and the authorities knew very little. I’m not judging it on moral or humanitarian grounds—it may well have been right—but geopolitically, it was disastrous. It left ordinary Germans feeling overwhelmed by people from unfamiliar cultures. As I said then, she wasn’t playing by the rules; it even conflicted with NATO obligations, since all members are supposed to secure their borders. That’s why I call Germany a ‘hippie state’—for Germans, the rules didn’t seem to apply.

So that has been a really big problem for Germany. I don’t think a further reinvention is needed, but I do think Germany is at a crossroads. The case for Europe and the European Union needs to be made even more strongly by Germany. It’s not so much a reinvention as a renewed push for Germany toward Europe—and that’s the only solution. Even in the UK, far more people now believe Brexit was a mistake than in 2016. The opportunity is there for Britain to help strengthen the European Union. It’s the only answer—for Herr Merz, for Viktor Orbán, for Monsieur Bardella. They may not like it, but Europe must be strengthened regardless.

Let’s look at the Ukraine-shaped elephant in the room – what does this new strategy mean for Ukraine, especially in the context of the ongoing peace efforts?

Over a million Russians killed or maimed in Putin’s demented war against Ukraine tells you that he is a murderous killer with no respect for human life, whether of Ukrainians or of his own people. That tells you all you need to know about the war criminal in the Kremlin. But the sad fact is that although the Russians cannot knock Ukraine out of the war, they appear to be winning.

What none of us understood was, first of all, that an American president would be so actively hostile to the idea of a sovereign Ukrainian state. Putin has whispered in Trump’s ear repeatedly: Ukrainians are losers. They’re losing. Ukraine is really part of Russia. This is a senseless, idiotic war. And Trump has come to believe that, despite the best efforts of Europe’s finest diplomats.

So I think you will find that however much we hate saying this, the time has come for Zelensky to trade Donbas and other areas to Russia in return for a ceasefire and a guarantee of boots on the ground from France, Germany, and Britain, in order to make this palatable to Zelensky and the Ukrainian people, who, of course, do not want to do any of this.

Do guarantees really exist? Earlier proposals offered only ‘assurances,’ recalling the Budapest Memorandum. Where are the guarantees, and will they materialize?

Well, as Mark Twain once said, you should never make predictions, especially about the future. All we can really talk about is what the deal on the table is. And I think the deal on the table now is quite clear, and what Sir Keir Starmer, Macron, and Merz will say to Zelensky is: look, we hate this almost as much as you hate it, but there is no alternative. You get a better deal now than you will get six months from now, and many more people will be killed for a worse deal. And no president can do that. You’ve got to bite the bullet. And that will be literal, because it will be the end of Zelensky.

Now you’ll probably ask me: can Putin be trusted to stick to it? Of course not. His track record is appalling. But what has changed — or what could change — is the leadership in Europe. Merkel was a very complicated figure. The first part of her political career was developed under the East German communist regime. If the Berlin Wall had not fallen, Frau Merkel — a gifted politician — would almost certainly have been in the East German Politburo. And there you had this very strong sense that Russia was your guardian. You were protected and made secure by them. Now there’s a different leadership. Macron is different. And whoever emerges as the British leader will be there — even Kemi Badenoch.

Yes, but Macron won’t be around for long. And Germany, as you’ve said, has quite an uphill struggle to undo the mistakes of the past. None of that gives Zelensky any assurance or any hope.

He has none, and it keeps me awake at night. Quite genuinely, I’m kept awake at night by the fate awaiting the brave Ukrainian people, and consequently wider Europe as well. All the time we are seeing ordinary people in Europe — in Britain, France, Germany — acting like ostriches, sticking their heads in the sand because they don’t want to hear what Putin has himself said about his primary wish to resurrect the geopolitical entity that was the Soviet Union. He has said he does not want the post-1997 NATO states to continue being part of the Alliance. And once he has swallowed Ukraine, he will start subverting and swallowing all the post-1997 states — and we’re talking about Poland too. It’s not just the Baltic republics and the smaller ones. We’re talking about really big and key players.

That’s what keeps me awake at night — that when my grandchildren come to adulthood, they will either be under Russian rule or in a war against it.

Which country looks most likely to be the next target for Putin’s military aggression? Poland is one of the biggest and best prepared — surely he would choose a weaker initial target? And what would be the likely European response?

I see developments in the following terms: first, a ceasefire which gives Putin what he has captured on the battlefield — and then some — in return for the guns falling silent. The next stage will be peace; this could take a few years. While it is being negotiated, I believe Putin will return to his policy of subversion in Ukrainian politics, resorting to all the tricks in his evil toolbox — poison, subversion, etc.

Meanwhile, I expect him to start more intrusive subversive measures against the Baltic republics and Poland, and almost certainly more covert meddling in German politics, trying to destabilize Merz, and building not just on the eastern German pro-Russian culture, but perhaps trying to re-establish even older tropes between some in the German army and intelligence services and their Russian counterparts. This is all part of Putin’s KGB playbook — slice by slice.

Yet just because Putin wants this to happen, it does not follow that it has to happen. The Russians are not ten meters tall. We need to retaliate, like with like. If their MiG fighters willfully intrude on our airspace, we should shoot them down, and we should spell out our intention to do so now, before there are any further intrusions. A more muscular European NATO can deter Putin.

Interview by Vazha Tavberidze