The One Caucasus Festival annually brings together Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Georgians through volunteer programs, collaborations, workshops, music, and more, to make progressive steps within the region.

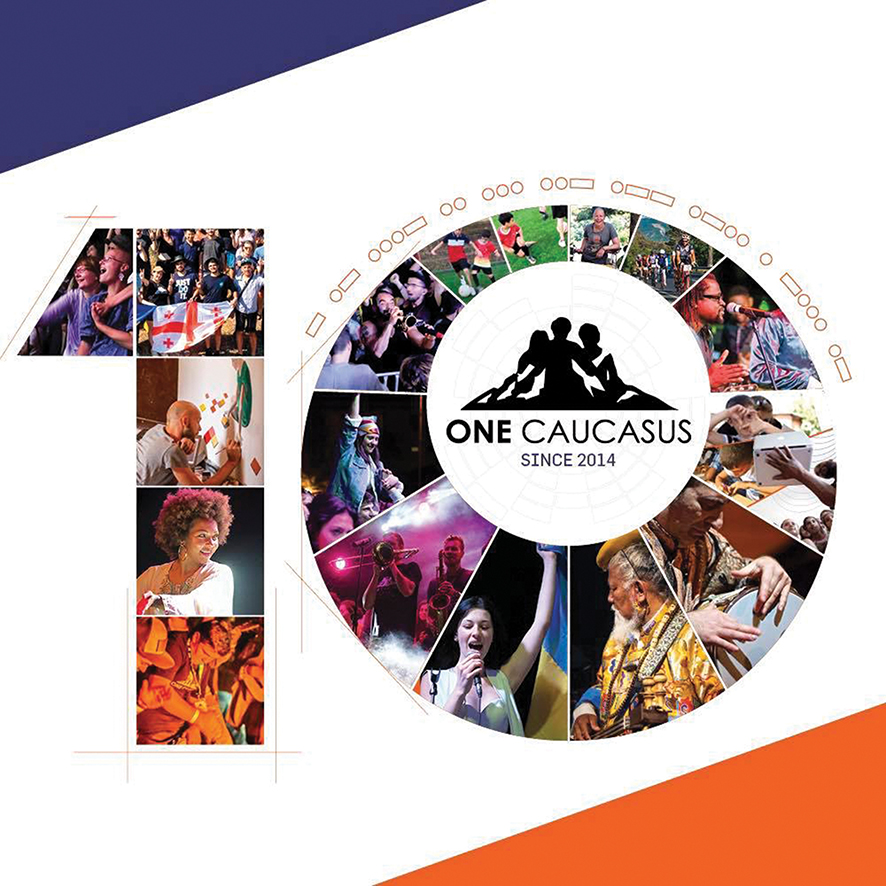

Established in 2014 and celebrating its tenth anniversary, One Caucasus is a four-day festival and NGO (non-governmental organization) in Georgia. In late August each year, in Tserakvi village in the Kvemo-Kartli region, musicians, educators, artists, and others come from around the world to participate in this event.

The Program Director and Initiator of One Caucasus, Witek Hebanowski, started a festival in Poland around 20 years ago called ‘Transcaucasia.’ He describes it as a modern-day ‘Woodstock’ and tells GEORGIA TODAY that his Caucasian friends who attended the event started questioning why they didn’t have something similar in their region to bring people together. Once the point had been raised, a team of people from at least seven countries brainstormed who the main audience would be for the One Caucasus festival.

Hebanowski says it was decided that the festival would target the youth of the region, and then the only thing left was to determine what type of Caucasus they wanted to display.

“[We wondered] do we want to present the Caucasus now? Or maybe create some kind of vision of the Caucasus and how it will work?” Hebanowski notes. “The first person who reacted was an Armenian curator, who said, ‘You got it.’ For me, that was the green light, because I wouldn’t dare to start such a project if it didn’t come from Azerbaijani, Armenian, and Georgian curators.”

The festival was held this year from August 24 to 27. There were 48 musicians in attendance, including 21 who were Georgian, 11 Armenian/Azerbaijani, and 16 international bands. In addition to the music, there were other projects and art galleries that people could view during the festival to learn more about the Caucasus region.

Since the festival is free of charge, Hebanowski said they do a large call for volunteers every year, from artists to educators, filmmakers, and more, to help put together and create content for the fest. According to Hebanowski, volunteers are split into workshop groups comprising people of different nationalities and trades, who are then sent to remote villages throughout the Caucasus to teach children skills. He said these could be different things such as how to edit movies or how to take photographs.

Once the volunteer groups are in the villages, Hebanowski told us they give the children a map of their village. This allows them to discover more about where they live, such as the history of the streets, people living in the area, monuments, etc., so they find their home more interesting. During this time with the volunteers, all the villages create something that is put on display at the One Caucasus Festival.

One product this year, Hebanowski says, was a trailer for a superhero and Harry Potter movie from an Azerbaijani village. The animation was voiced over by the children and had various parodies that were collected into one piece. After the post-production was completed by the One Caucasus team, the video was shown to the festival’s audience.

This year, the festival had a space known as the Gallery of Modern Art, (GoMA) which was full of tablets. Each displayed a different project curated by the various villages so people could look across borders, see what is being produced around the Caucasus, and learn about the areas. Another collaborative part of the festival looking across borders is to create mixes between different musicians.

According to Hebanowski, there were at least 10 collaborations between musicians from various countries. What he found most amazing was that the audience didn’t notice different bands on one track; rather, they thought it was one group.

Hebanowski told GEORGIA TODAY that he is glad that their team is comprised of people from the Caucasus, but notes that things have gotten harder in recent years.

“We are happy to have a team, especially working with Armenians and Azerbaijanis. One Caucasus has offered many training sessions on the power of mediation and negotiation regarding how to solve the Karabakh problem, and in One Caucasus there’s the practice of working together,” Hebanowski says.

“We now have Armenian bands who wanted to go onstage with Azerbaijani bands, but the problem was that because the border was closed with Azerbaijan, we lost the biggest metropolitan audience.”

In 2019, more people came to the festival from Baku than from Tbilisi, though the primary audience is the local Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian residents. When the One Caucasus team was searching for a place to hold the festival, they wanted to find somewhere easily accessible and close to all three Caucasian borders. Hebanowski said they were shocked when they found Marneuli, just north of Tserakvi, because it was a “complete kaleidoscope of the Caucasus,” with Azerbaijanis, Sunni and Shia, Armenians, and Georgians.

Irakli Mikiani is the founder of the One Caucasus NGO. He said that this year’s festival was the biggest festival they have had, however, it didn’t come without caveats. He said it took them a while to secure confirmation of the festival, and that One Caucasus is always associated with numerous topics and issues that people face daily. Even though they often hit these roadblocks, Mikiani said the team has learned to make light of the situation and push through, because the festival “simply must happen.”

Between the festival and the NGO, work is happening year-round. In three locations each year, there is a program led to promote architecture. Groups of volunteers go where the government is willing to invest, and they coordinate with the local people to develop architectural ideas that the community wants to implement.

Hebanowski also says that every year a volunteer construction team builds platforms for the festival – including a cinema, furniture, signs, the GoMA, and more, while other teams are sent to villages in the Caucasus to build small houses dedicated to integrating games and inspiring youth.

Looking forward, the team says they are focused on the next two years and reaching out to big-name artists, so people around the globe can support the One Caucasus cause and turn Tserakvi into a place where people meet.

“We see that after war there is this need. It is very important to us to use One Caucasus as a place where Armenians and Azerbaijanis can meet as human beings, not enemies,” says Hebanowski. “We see this need amongst young people.”

According to the team, everyone has a One Caucasus story. They aim to take small steps that will make a difference rather than take on something larger than themselves.

By Shelbi R. Ankiewicz