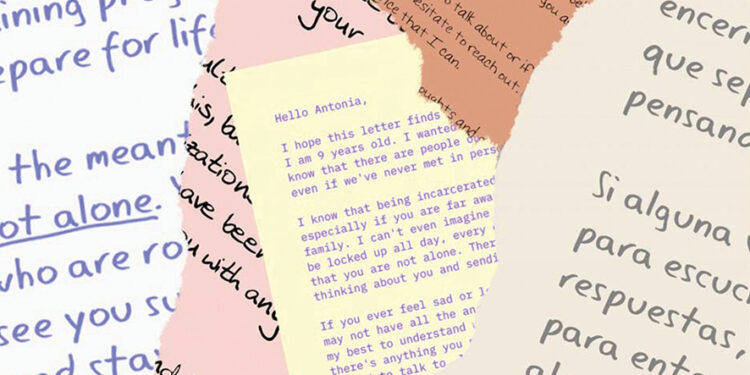

It begins, improbably, with a Google form. You type a few sentences, pick a name from a list of sixty-three prisoners, and agree to a declaration—“Freedom to prisoners of the regime, fire to the oligarchy.” Somewhere in Georgia, activists print your words on paper and deliver them to a prison cell.

The gesture is almost anachronistic. We live in a time when politics is measured in clicks, when a protest can erupt on Telegram before it reaches the streets. And yet, the act of writing to a prisoner—a stranger, someone whose name you may only know from a list—is as old as dissent itself. The message may be simple: we are thinking of you. But behind it lies a tradition that stretches from the gulags of the Soviet Union to the jails of the American South, from Robben Island to present-day Russia.

Political letters, unlike most correspondence, are written with two audiences in mind. There is the recipient—the prisoner who reads them as lifelines. And there is history, which tends to collect them like artifacts. Vaclav Havel’s Letters to Olga turned his confinement into a philosophical diary. Martin Luther King Jr., scribbling on scraps of newspaper in Birmingham Jail, fashioned a manifesto for civil rights. Mandela’s prison letters were so heavily censored that they sometimes read like coded poetry, yet they preserved his political identity through decades of isolation.

The Georgian platform inserts itself into this lineage. But where Havel labored over sentences for days, the twenty-first-century writer performs the act in minutes, on a phone. Solidarity has been streamlined. It travels at the speed of Wi-Fi. In the age of envelopes and stamps, a letter to a prisoner carried weight, in part because of the time and trouble it demanded. The handwriting, the trip to the post office, the anxiety over whether it would reach its destination—this was solidarity with calluses. By contrast, an online form makes the act frictionless. Solidarity is now only a few keystrokes away, which is to say: it risks becoming indistinguishable from everything else we do online.

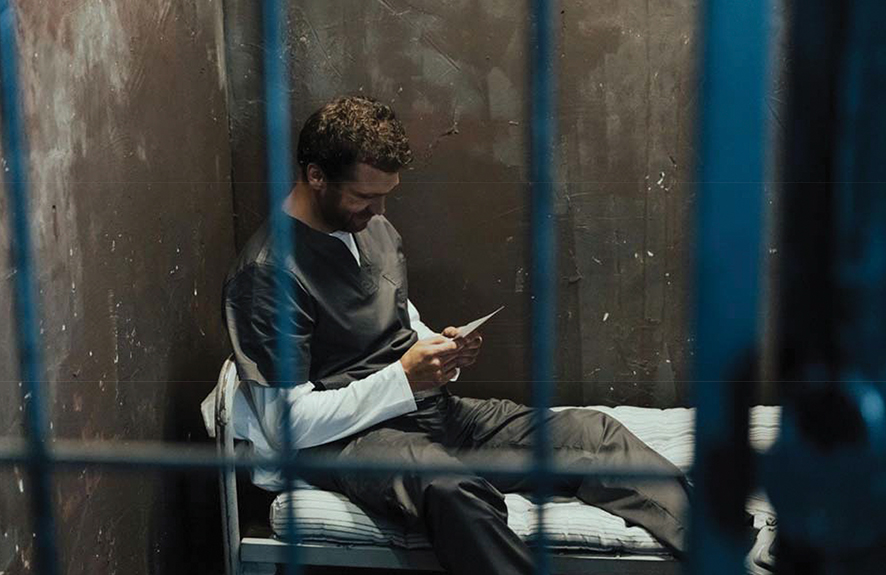

Still, the form retains its force. To send a letter is to insist that someone locked away has not disappeared. Michel Foucault once described prison as a machine of silence, a place where speech is confiscated along with freedom. A letter slips through that silence.

Anthropologists might call it a ritual of care. You reach toward someone you do not know, someone the state has tried to erase from public life, and you declare, however briefly: you remain visible. This act, repeated across dozens or hundreds of writers, becomes a chorus. Durkheim would have called it “collective effervescence”—a secular liturgy that binds people together.

The point is less the content of the letter than the gesture itself. The prisoner learns that their name circulates outside the prison. The writer learns that their words, however small, have a destination in the dark. Both sides participate in a ceremony of recognition.

Of course, nothing is neutral. To send a letter through the Georgian platform, one must first agree to the slogan: “Freedom to prisoners of the regime, fire to the oligarchy.” It’s a litmus test of allegiance, a reminder that solidarity is always entangled with politics.

Habermas might bristle at this—the public sphere, in his model, is meant to foster free and unconstrained communication. Yet Antonio Gramsci would have smiled knowingly: every counter-hegemonic movement depends on ritual, slogans, repeated affirmations. To sign the declaration is to join a collective voice, not just to comfort an individual.

Here lies the dual nature of the practice. On one hand, it is intimate, almost tender: strangers writing to the confined. On the other, it is overtly political, a way of amplifying dissent. The prisoner becomes both a person and a symbol, and the letter serves both roles at once.

If all this feels steeped in European history, it’s because the letter has always been the medium of exile.

The Decembrists, banished to Siberia in the nineteenth century, sent letters that became legends. In apartheid South Africa, Winnie Mandela guarded her husband’s censored notes as if they were relics. In the Soviet labor camps, prisoners tucked malinki—tiny letters—into food or clothing, a network of messages that testified to survival.

Even today, the practice persists. Navalny’s dispatches from Russian prisons are still posted online and circulated as if they were state-of-the-nation addresses. The letter refuses to die. It remains the slow weapon of the weak.

We live in cynical times, when political action is measured by its virality, when solidarity risks collapsing into hashtags. Against this backdrop, the Georgian initiative feels oddly earnest. To write to a prisoner is not glamorous; it doesn’t produce a dopamine spike of likes or shares. It is, instead, a small act of civic decency.

And perhaps that is precisely what makes it powerful. Societies are remembered for how they treat their prisoners—not only in law and punishment, but in whether those behind bars are allowed to vanish. To write a letter is to refuse that vanishing.

The archives of the future will include these letters. Historians will read them the way we now read Havel or Mandela: as fragments of a time when words tried to pierce walls. And maybe, just maybe, it will be these fragile sheets of paper—printed from a Google form—that tell the most durable story of what solidarity looked like in Georgia in the 2020s.

By Ivan Nechaev