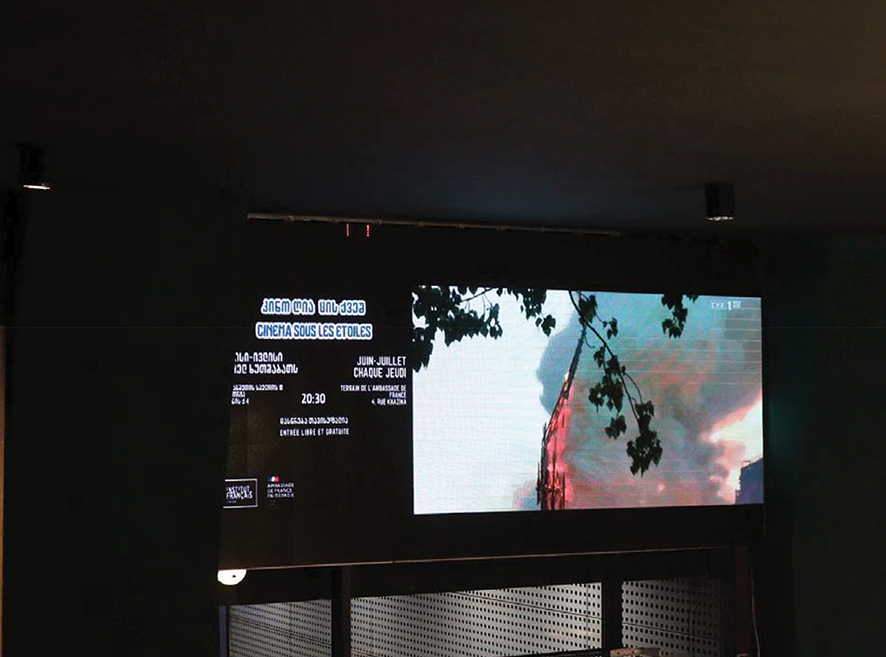

In a cinematic summer that stretches from June to the edge of August, a constellation of films quietly rewires the cultural map of Tbilisi. The annual festival Cinéma sous les étoiles, initiated by the Institut français and the French Embassy in Georgia, is an elegant and necessary intervention into the rhythms of the city, a gift of aesthetic plurality, emotional complexity, and timeless Frenchness, shared in the most democratic of ways: for free, in the open air, in the space between two languages.

This year’s edition, running from June 5 to July 31, marks a particularly rich and resonant curation. Combining modern and classic works, animation and documentary, family-friendly tales and probing adult dramas, it showcases the broad palette of contemporary French cinema while reviving older masterpieces that remain vibrantly alive in today’s world. Every Thursday evening at 20:30, on the grounds of the French Embassy on Khazina Street (with the exception of the June 5 opening at Amirani Cinema), Georgian audiences are invited to immerse themselves in a world where cinema is not a commodity, but a shared dream.

French Cinema as Memory, Movement, and Multitude

The program opened with a cinematic requiem: Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Notre-Dame brûle (2021), a visceral dramatization of the 2019 Notre-Dame fire. A blend of documentary precision and thriller pacing, it reflected Annaud’s obsession with architectural fate, collective trauma, and the sublime absurdities of institutional machinery. It was also a reminder that French cinema could engage the symbolic, political, and technical simultaneously—an ideal inaugural gesture for a festival that sought to bridge past and present.

From there, the selection fans outward. On June 12, L’Odyssée (2016) by Jérôme Salle presents a biopic of Jacques-Yves Cousteau, that mythic hybrid of scientist, adventurer, narcissist, and poet. The film is a rare feat: a popular biography that doesn’t collapse into hagiography. It allows us to see not just the marine landscapes but also the emotional and ideological abysses of a postwar France grappling with the idea of heroism.

Next, En Fanfare (June 19) offers tonal contrast: an intimate, idiosyncratic comedy about identity and fatherhood, a chamber piece on the comedic potential of generational misrecognition. Then comes Ernest et Célestine – Le voyage en Charabie (June 26), a tender, painterly sequel to the beloved animation franchise. With its gentle critique of authoritarianism cloaked in a whimsical fable, it functions as a politically lucid gift for children—and a reminder that animation is one of France’s most refined cinematic traditions.

Georgia in France, France in Georgia

On July 3, a thematic pivot transforms the festival. Le Paris des Géorgiennes, projected in French with Georgian subtitles, offers a rare reversal of the usual cultural optics. Rather than French directors gazing out at the world, we see Georgian women navigating the labyrinths of Paris—its promises, alienations, and the strange intimacy of foreign belonging. This film is a documentary not just of migration but of affect: how language, labor, and memory entangle in diasporic life. For a Tbilisi audience, it is an act of self-recognition across borders. This choice signals a profound understanding by the festival curators: that the politics of cultural exchange must sometimes involve giving the mirror to the other.

On Love, Shame, and the Tenderness of Old Films

On July 10, Chronique d’une liaison passagère (2022) by Emmanuel Mouret delivers a deceptively minimalist drama about fleeting love. With its Rohmerian rhythm and disarming intelligence, it speaks in a language of glances, hesitations, and unspoken codes. Here, French cinema returns to its most prized aesthetic: the moral conversation as erotic form.

This is followed by L’argent de poche (July 17), a 1976 classic by François Truffaut. One of the most celebrated portraits of childhood ever committed to film, it blends vignette with reverie, cruelty with innocence. Truffaut, the godfather of the New Wave, appears not only as director but as a kind of historical ghost throughout this festival, reminding us that the French cinematic tradition always carries a double burden: to modernize and to mourn.

On July 24, Je verrai toujours vos visages (2023) by Jeanne Herry enters the conversation as one of the most affecting and socially relevant films in recent French cinema. Focusing on restorative justice and the complex dialogues between victims and offenders, it wrestles with themes often ignored in both film and public discourse. It is a documentary-like drama that neither sentimentalizes nor flattens pain but structures it within a collective therapeutic process. Watching it in Georgia—a society still bearing many invisible wounds—lends it urgent relevance.

Finally, the festival closes on July 31 with Àma Gloria (2023), directed by Marie Amachoukeli, whose own Georgian heritage bridges the festival’s emotional geography. A film about the bond between a little French girl and her Cape Verdean nanny, it explores absence, memory, and the slow crystallization of loss through a child’s perspective. Its images linger like dreams that refuse to leave.

A Cultural Strategy for Empathy, Thought, and Aesthetic Education

What unites this diverse program is neither genre nor ideology, but something deeper: a belief in cinema as emotional pedagogy. These films teach how to grieve (Notre-Dame brûle), how to imagine futures (L’Odyssée), how to live with contradiction (Chronique d’une liaison passagère), and how to recognize each other across languages and borders (Le Paris des Géorgiennes, Àma Gloria).

Moreover, the choice to subtitle films in English or Georgian—rather than dubbing them—preserves the auditory texture of the French language. This respects both the original artistic intent and the linguistic sovereignty of the audience. It also opens access without flattening difference.

For Georgian viewers—many of whom grew up under the legacy of Soviet-era French cultural prestige—this festival is a reconnection, not just an introduction. It reminds us that French cinema is still one of the world’s most sophisticated mirrors for human experience.

And for younger audiences encountering these films for the first time, it is a form of aesthetic education rarely offered in mainstream cinema spaces. It says: film can be quiet, complex, slow; it can contain questions without answers; it can show you the world without explaining it.

In a summer where entertainment is increasingly algorithmic and cinematic space ever more commercialized, Cinéma sous les étoiles provides something rare: a non-transactional, communally curated, affectively generous experience.

By Ivan Nechaev