Kammerballetten’s appearance at the Tbilisi Ballet Festival felt like a tectonic shift. Curated by Danish ballet visionary Tobias Praetorius and framed by the unflinching eye of artistic director Nina Ananiashvili, this program of chamber-scale ballets drew together some of the most feverish choreographic minds of our time—Paul Lightfoot, Hans van Manen, Emma Portner, Sebastian Kloborg—and cast them like lightning bolts across a Georgian stage.

The effect was cinematic, personal, at times brutal. This was no gala, no parade of virtuosic pleasantries, but an anatomy of dance as psychological theater, love letter, hauntology. Over the course of two acts, chamber music and minimalist staging laid bare the tremors beneath the flesh of contemporary ballet, as if the entire evening were unfolding in the interior space of the body—viscera before spectacle, pulse before poise.

The New Classical in Dialogue with the Now

The evening opened with SARCASMEN, a quintessential Hans van Manen exercise in distillation. To Prokofiev’s biting “Five Sarcasms,” the duo of Salome Leverashvili and Timothy van Poucke—both principal dancers of the Dutch National Ballet—offered a textbook lesson in spatial architecture. Van Manen’s choreography, all dry wit and wry glances, probes the negative space between dancers as much as their limbs. Leverashvili’s command of angles and muscular wit played beautifully off van Poucke’s controlled lyricism. It was a cool beginning, a taut overture to the emotional bloodletting that followed.

That came in OTHER LITTLE STORIES, a poignant duet by Amilcar Moret Gonzalez, danced by Georgian star Nino Samadashvili and the increasingly arresting Giorgi Potskhishvili. Set to the post-minimalist melancholy of Ezio Bosso, this was chamber ballet as whispered memory. Samadashvili moved like a breath suspended between confession and disappearance; her hands trembled with unspoken dialogue. Gonzalez’s choreography favors the unspooling of time—small, fractal gestures, dislocated unisons, emotional aftershocks. It was one of the evening’s rare moments of deep quiet.

Then, ONCE I HAD A LOVE arrived like a vinyl record slashed with a blade. Sebastian Kloborg, with Maria Kochetkova, summoned the ghost of Blondie into a duet of emotional entropy, crashing new wave nostalgia into the fractal structures of Philip Glass. Costumed in GANNI, the Danish fashion house, they seemed like icons resurrected from some arthouse apocalypse. Kochetkova danced like a pop goddess unraveling at the seams, and Kloborg—choreographer and co-performer—exuded the energy of a man dancing with the shards of a past life. Here, ballet was a medium for cultural dissonance, not harmony.

In ELEPHANT, Emma Portner, a choreographic oracle of movement-as-ritual, performed alongside Toon Lobach in an otherworldly fusion of contemporary dance, video-game geometry, and gothic decay. Portner’s body is a grammar of collapse and recoil, and this duet, accompanied by live musicians and haunted by the music of Peteris Vasks and Mirel Wagner, was a dirge in motion. Here, ballet became sedimentary—layered, broken, regrown.

With NEUE BAHNEN, Praetorius offered a love letter to Brahms—and to the vanished idea of pure duet. Alban Lendorfand Emilie Palsgaard embodied a shared center of gravity, their phrasing rooted in the Romantic but destabilized by subtle asymmetries. The musical trio—Emma Baird, Alexander McKenzie, Toke Moldrup—performed with a chamber ensemble’s attentiveness, allowing breath to drive both sound and step.

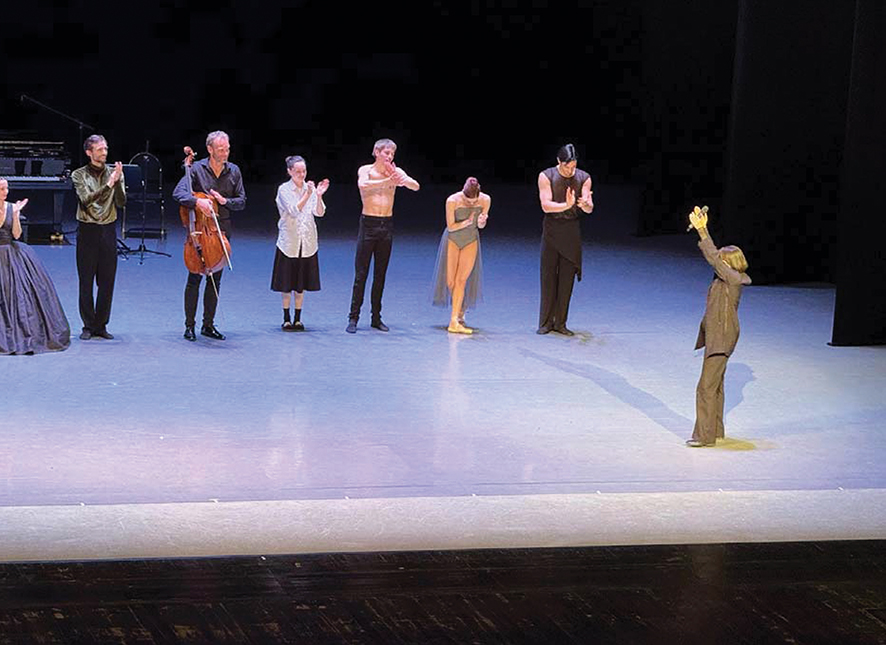

The act closed with THE GUST, Kloborg’s understated jewel—a duet with “a special guest” revealed to be none other than Nina Ananiashvili herself. Her appearance drew a collective intake of breath from the Georgian audience, a queen stepping out of the wings. But this was no cameo. Kloborg and Ananiashvili danced with a silence that said more than movement. Here was a meditation on legacy, time, and the dignity of presence. In an age obsessed with youth, Ananiashvili’s return felt like an act of aesthetic resistance.

Chamber Ballet as Existential Reflection

The second act comprised a single, long-form work: SELVPORTRAT by Paul Lightfoot. This was the psychological climax of the evening—less a portrait than a psychic excavation. Featuring Maria Kochetkova, Toon Lobach, and Sebastian Pico Haynes, the piece explored grief, memory, and identity through a shifting interplay of trio forms. Alexander McKenzie’s score, performed live once again, wove an eerie intimacy into the space.

Lightfoot’s choreography is a cinema of angles and ruptures: sudden drops into the floor, bodies that cling and then repel like mismatched magnets. The lighting design—a bruised palette of sepia and pale neon—suggested an attic of memory. Each dancer felt like a version of the same self, refracted across timelines. Kochetkova moved with glassy anguish; Lobach offered control dissolving into doubt; Haynes, all volatile elegance, stitched the scenes together with uncanny force.

If classical ballet taught us to build mythologies, Lightfoot’s chamber ballet dismantles them. SELVPORTRAT is deeply human—wounded, uncertain, suffused with longing.

Curation as Choreography

What makes the Kammerballetten appearance at the Tbilisi Ballet Festival so resonant is not only the quality of individual works, but the curatorial arc. Nina Ananiashvili has long understood that ballet’s future lies in the fertile soil between forms, between genres, between ages. By inviting Kammerballetten, she brought Georgia into the intimate, radical present of European dance.

This was ballet without hierarchy. Dancers, musicians, choreographers, and designers functioned as a single kinetic organism. The program unfolded like a suite of letters from a future that still remembers its past.

In a city where dance is often framed by the monumental, Kammerballetten offered a miniature opera of emotional precision. It whispered what others shout. And in that whisper, we heard something rare: a ballet of truths, unvarnished, unguarded, and urgently now.

Review by Ivan Nechaev