In Limassol, sometime between Borya Gadai’s first hesitant prophecy and his final glance toward a world that has never quite rewarded innocence, a woman in the third row began to cry — openly, without theatrical restraint. She was not alone. By the end of The Autumn of My Springtime, the Rialto Theater had turned into that rare civic space where adults allow themselves the dangerous luxury of feeling.

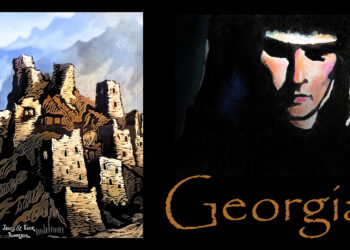

Gabriadze Theater arrived in Cyprus for the first time at the end of January. Over seven performances, in Limassol’s Rialto Theater and at Pallas Theater in Nicosia, the company presented Alfred and Violetta and The Autumn of My Springtime. Every evening was sold out. The statistic carries weight, yet the atmosphere carried more. What unfolded on the island felt closer to recognition than to novelty. The tour took place with the support of the VF Foundation and in collaboration with Celebrity Gala. Cultural logistics made it possible; art made it necessary.

Gabriadze Theater, founded by Rezo Gabriadze, has always worked in miniature scale while thinking in metaphysical dimensions. The puppets are visibly manipulated. The stage machinery remains exposed. Lighting sculpts intimacy rather than spectacle. Leo Gabriadze’s direction preserves the fragile rhythm of the original texts. Veronika Gabriadze sustains the production ethos with curatorial precision. The ensemble of puppeteers, Tamar Amirajibi, Tamar Kobakhidze, Giorgi Giorgobiani, Imeda Guliashvili, Medea Blidze, Mikhail Barnov, perform with disciplined invisibility that paradoxically heightens presence. The audience sees the hands and then forgets them.

The performances were presented with translation in three languages. Linguistic mediation functioned as a bridge rather than a filter. Gabriadze’s dramaturgy rests on gesture, silence, musical cadence, the trembling delay before confession. Meaning traveled easily across languages.

Created in 1983, The Autumn of My Springtime remains one of the most distilled articulations of Gabriadze’s moral universe. Set in post-war Kutaisi, it follows Borya, a small bird who evolves from street fortune-teller to accidental outlaw to wounded romantic. Around him, the city limps forward after catastrophe. His grandmother Donna bends under invisible weight. The organ grinder Varlam carries time in his barrel organ. Love appears, fragile and compromised. History presses in from every side.

In Cyprus, this Georgian post-war landscape resonated with particular force. The island’s own twentieth century, marked by division and displacement, lent additional depth to the reception. No explicit parallels were drawn; none were required. The emotional architecture did the work. The audience understood what it means for a child to grow up too quickly. They understood the stubborn dignity of small lives.

There was no polite, festival-style quiet in the hall. There were audible sighs. There were suppressed sobs that eventually stopped being suppressed. During Borya’s quiet reckoning with loss, the air in the theater seemed to thicken. Puppet theater, in lesser hands, invites condescension. Here, it dismantled it.

Alfred and Violetta offered a different temperature: a chamber meditation on love’s fragile geometry.

The production traces how a fleeting spark matures into attachment and then collides with fear, expectation, inner fracture. The puppets move with a delicacy that borders on vulnerability; their physical smallness intensifies the emotional stakes. The visible strings become a philosophical proposition: every love story carries its own mechanism of constraint.

Across the seven evenings, the theater generated a rare form of collective intimacy. These are works created for small spaces; they resist bombast. In Limassol and Nicosia, that scale proved transformative. The audience leaned forward. Laughter arrived unexpectedly and dissolved just as quickly, giving way to something heavier and more luminous.

Gabriadze theater has traveled internationally for decades, from New York to Paris, yet Cyprus marked a charged debut. The island did not receive the company as an exotic guest. It received it as a mirror. After the final curtain in Nicosia, applause rose slowly, gathered momentum, and refused to subside. People stood. Some wiped their faces. Others remained seated for a moment longer, recalibrating to ordinary reality.

As an art form, puppetry often occupies the periphery of serious discourse. Gabriadze’s work renders that hierarchy obsolete. What was presented in Cyprus is a theater of ethical memory. It speaks about childhood without sentimentality, about loss without melodrama, about love without illusion. It insists that fragility can carry intellectual weight.

On an island shaped by light, these winter performances brought a different illumination: inward, searching, precise. A small bird from Kutaisi flew across the Mediterranean and, for seven evenings, rearranged the emotional topography of two Cypriot cities.

The measure of success revealed itself in a simple gesture: people leaving the theater in tears, reaching for their phones, compelled to call someone they love. In cultural terms, that remains a rare achievement.

By Ivan Nechaev