On a crisp winter morning, passersby on Chavchavadze Avenue were drawn to an unexpected exhibition outside Ilia State University’s main building. Students had arranged a striking display of objects—banned fireworks, lasers, balaclavas, gas masks, and even a seemingly innocuous blank sheet of paper—transforming these ordinary items into potent symbols of dissent. The student-led initiative was more than an act of artistic defiance: it was a statement on the absurdities, contradictions, and authoritarian tendencies of Georgia’s ruling party, Georgian Dream.

This provocative installation was not merely about the items on display but what they signify: fear, repression, and resistance. Each object carried a story; a sociopolitical resonance that critiques the government’s paranoia and its attempts to control public discourse. Below, we delve into the layers of meaning behind these objects, and explore why they have become symbols of fear for Georgia’s ruling elite.

Objects of Fear: A Semiotic Analysis

Fireworks, Lasers, and Balaclavas: Recently banned by Georgian Dream, fireworks and lasers have been redefined as tools of rebellion. Their prohibition speaks to a deeper anxiety: the unpredictability of mass gatherings. These bans recall the June 2019 protests, where lasers were used to disorient riot police, and the government retaliated by categorizing these harmless lights as weapons. Similarly, the balaclava, a garment associated with both protestors and masked repression, stands as a dual symbol of anonymity and defiance.

The “Male Milk” Controversy: One of the most surreal elements of the exhibition references Georgian oligarch and former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili’s assertion that “in the West, male milk is equated with female milk.” This bizarre statement, which sparked ridicule across social media, epitomizes the anti-Western rhetoric employed by the ruling party. The students’ inclusion of this reference underscores the absurdity of such moral panics, framing them as distractions from real issues like economic stagnation and democratic backsliding.

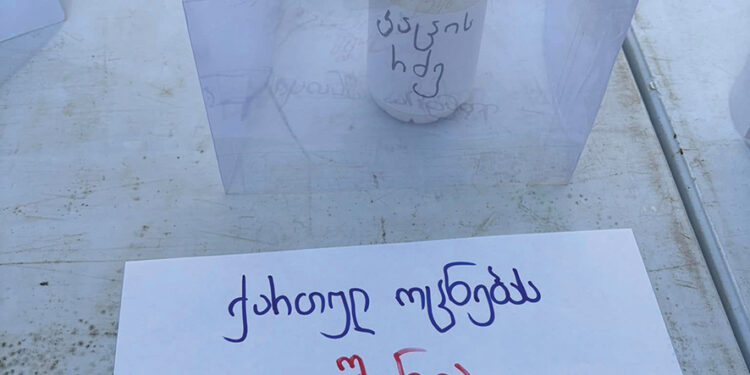

The Blank Sheet of Paper: Perhaps the most potent symbol in the exhibition is the blank sheet of paper. Protestors, arrested for simply holding empty sheets, demonstrated the absurd lengths to which the government would go to suppress dissent. The paper is a paradox: simultaneously nothing and everything. It is an empty canvas for resistance, a haunting reminder of the state’s fear of free thought.

The Politics of Fear: A Broader Perspective

Georgian Dream’s responses to these symbols reflect a broader trend in authoritarian governance: the weaponization of fear. In sociological terms, fear serves as a tool to consolidate power by creating an “us vs. them” narrative. Here, the “us” represents the guardians of Georgian tradition, while the “them” becomes an ever-expanding list: protestors, Western liberal values, and even mundane objects like fireworks or blank sheets.

This phenomenon can be understood through anthropologist Mary Douglas’s theory of ‘purity and danger,’ which posits that societies create taboos to reinforce boundaries. For Georgian Dream, these boundaries are ideological—protecting a vision of Georgian identity that is both nostalgic and exclusionary. Anything that challenges this narrative, even humor or satire, is perceived as a threat.

Protest as Performance: The Power of Satire

By turning everyday objects into political statements, the students of Ilia State University were engaging in a form of carnivalesque protest. Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the carnival—where hierarchies are temporarily overturned and the absurd is celebrated—aptly describes their approach. Through satire and subversion, they expose the fragility of power structures that cannot tolerate even symbolic challenges.

The humor inherent in the exhibition (‘Georgian Dream Fears Male Milk!’) was a powerful counterbalance to the oppressive seriousness of the state’s rhetoric. It disrupts the language of fear and replaces it with ridicule, a strategy historically effective in challenging authoritarian regimes.

The Real Fear

The objects displayed at Ilia State University’s exhibition were not inherently dangerous. What makes them frightening to Georgian Dream is the meaning ascribed to them by a generation that refuses to be silenced. Fireworks, blank sheets, and balaclavas become emblems of a broader struggle: the fight for free expression, accountability, and a vision of Georgia that is open, democratic, and inclusive.

In the end, it is not the objects themselves that Georgian Dream fears: it is the students—their creativity, their courage, and their ability to transform fear into resistance—that pose the greatest threat. As the exhibition boldly proclaims, “Georgian Dream fears your voice, your knowledge, your whistle, and your blank page.” What they fear most, however, is the unstoppable momentum of a generation unwilling to live in silence.

By Ivan Nechaev