Every once in a while, an exhibition appears that does not merely present art, but recalibrates the cultural self-image of a city. Tbilisi is living through such a moment now. The simultaneous opening of Merab Abramishvili – Transparent Memory across three venues—ATINATI’s Cultural Center and Baia Gallery’s two exhibition spaces—feels less like a curatorial coincidence than a collective decision to finally speak in a grown-up voice about Georgian painting, its history, and its unresolved ambitions.

This is not an anniversary show. Nor is it a commemorative gesture dressed up as scale. What we are witnessing is something rarer and more consequential: the consolidation of an artist into an intellectual, institutional, and symbolic axis around which the entire year’s cultural conversation begins to rotate.

For decades, Georgian art has suffered from a particular kind of modesty—half inherited from Soviet cultural bureaucracy, half self-imposed after independence. Even major artists were shown cautiously, in fragments, as if too much confidence might provoke historical irony. The Abramishvili mega-exhibition breaks with this habit decisively.

Three spaces. One curatorial narrative. A catalogue, a digital archive, lectures, collectors’ meetings, and full insurance coverage for a dispersed body of works. These details matter. They signal that Georgian art has stopped asking for permission to be taken seriously and has begun constructing its own infrastructure of legitimacy.

This is why the exhibition reads as an event rather than a display. It does not merely ask viewers to look; it asks institutions to commit.

Merab Abramishvili has often been described in stylistic terms—religious painter, iconographic modernist, metaphysical fabulist. This exhibition quietly dismantles those shortcuts. Seen at scale, across three curatorial strategies, Abramishvili reveals himself as something more structurally ambitious: a painter of systems.

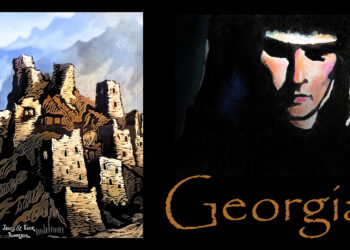

At ATINATI’s Cultural Center, The Collector’s Choice presents a near-classical argument. Around forty works unfold as a continuous visual grammar, where gardens, animals, saints, and human figures circulate within a closed but infinitely renewable universe. Here, Abramishvili’s work reads almost musically, with themes returning in altered tonalities. The logic is cumulative rather than episodic. One painting does not explain the next; it deepens it.

Baia Gallery’s dual spaces introduce productive friction. Multimedia elements, archival research, and digital extensions pull the paintings into historical time: the collapse of Soviet ideology, the ethical exhaustion of the late twentieth century, the reappearance of faith as an existential tool rather than a doctrinal one. Abramishvili emerges not as a solitary mystic but as a thinker negotiating cultural debris.

The tension between these approaches is deliberate—and illuminating. ATINATI frames Abramishvili as a cosmology; Baia frames him as a case study in cultural survival. Together, they allow the artist to resist both sanctification and reduction.

Abramishvili belonged to the generation of the 1980s, a cohort that came of age as the Soviet narrative imploded. Many artists of that moment responded with irony, conceptual detachment, or political negation. Abramishvili chose something far less fashionable and far more dangerous: construction.

His paintings do not protest the collapse of ideology. They simply replace it.

Using levkas—a technique historically tied to medieval Georgian wall painting and iconography—Abramishvili does not imitate tradition so much as absorb its temporal logic. His surfaces feel ancient because they reject linear time. Paradise in his work is not a lost origin point; it is a recurring condition. Gardens regenerate. Animals circulate as metaphysical equals. Figures exist within a moral ecosystem rather than a narrative hierarchy.

In sociological terms, Abramishvili offers what late modernity rarely does: a closed value system that does not feel authoritarian. His universe operates on coherence rather than control. Harmony functions as structure, not sentiment. This is precisely why his work resonates now. In a cultural climate exhausted by deconstruction, Abramishvili’s insistence on meaning feels quietly radical.

One of the exhibition’s most significant achievements lies beyond aesthetics. ATINATI’s role as a collector and repatriator of Abramishvili’s works introduces a new ethical model into Georgia’s art ecosystem. These paintings, recovered from international auctions and private collections, return not as nationalist trophies but as shared intellectual property.

Baia Gallery’s decades-long stewardship—research, exhibitions, Sotheby’s presentations, now a comprehensive digital platform—completes the institutional triangle. The collaboration between gallery, foundation, state-supported digital initiatives, and private insurers marks a threshold moment. Georgian art is no longer treated as fragile symbolism; it is treated as material history requiring protection, documentation, and long-term thinking.

Even the fact that this is the first exhibition of such scale in Georgia to be fully insured as a unified corpus feels emblematic. Value here is not rhetorical; it is operational.

The title Transparent Memory is deceptively precise. Abramishvili’s work does not monumentalize memory; it renders it permeable. His paintings function less as recollections than as environments one enters. They produce the uncanny sensation of recognition without recollection—as if the viewer has been here before, somewhere between myth and childhood.

This transparency is not softness. It is structural clarity. Abramishvili believes—visibly, insistently—in the possibility of coherence. In painting. In culture. In life’s continuity beyond historical rupture. This exhibition reveals what Georgian culture looks like when it abandons defensive irony and allows itself seriousness at scale.

Merab Abramishvili appears here not as a local master awaiting international validation, but as an artist whose internal logic feels urgently legible beyond borders. His work speaks fluently to a world searching—again—for systems of meaning that do not collapse under scrutiny.

Three spaces. One painter. A city briefly aligned with its own depth. This is what cultural adulthood looks like.

By Ivan Nechaev