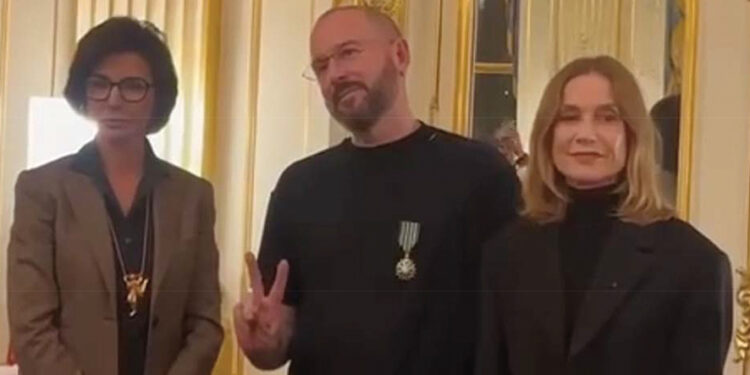

When French Minister of Culture Rachida Dati fastened the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres onto Demna Gvasalia’s torn T-shirt, it was more than just a moment of recognition. It was a performative contradiction, a ritual both of inclusion and disruption. The Georgian-born designer, who fled war-torn Abkhazia as a child, has spent his career dismantling the very institutions that now honor him. And yet, there he stood in Paris—fashion’s most rebellious auteur, anointed by the establishment he so often satirizes.

This paradox is the essence of Demna’s creative identity. A refugee who became the architect of luxury’s new nihilism; a self-exiled Georgian who reimagined Western high fashion through the raw textures of post-Soviet aesthetics; a designer who sells dystopia as couture, making Paris itself bow to the disheveled glamour of the displaced. But what does it mean for an enfant terrible to receive an official seal of approval? Has Demna’s revolution become an institution, or has he simply redefined the institution itself?

From Exile to Empire: Fashion as a Memory Machine

Demna Gvasalia’s trajectory—escaping war, moving between cultures, and forging an identity in exile—is central to understanding his aesthetic. He was born in 1981 in Soviet Abkhazia, a region that would soon become a flashpoint in the violent post-Soviet collapse. When war broke out in 1992, his family fled to Tbilisi, and then to Germany, uprooted by forces beyond their control.

Fashion, for Demna, is not merely an industry, but a deeply personal act of memory. His work at Vetements and Balenciaga channels the visual language of displacement: oversized silhouettes that swallow the body, fabrics that recall survivalist pragmatism, and an unrelenting interrogation of luxury’s artifice. The tattered hoodie, the trash-bag handbag, the exaggerated shoulder pads—they are not just aesthetic choices but echoes of migration, of people carrying their world on their backs.

In this sense, Balenciaga under Demna is more than a brand; it is a conceptual space where trauma, nostalgia, and social critique intertwine. It takes the debris of the past—whether Soviet tracksuits or counterfeit market culture—and repackages it as high fashion. For Demna, exile is not just a personal history; it is a design philosophy.

Fashion’s Prankster or Its Prophet?

Since taking over Balenciaga in 2015, Demna has waged an ongoing war against fashion’s sacred cows. He has transformed runway shows into spectacles of bleak absurdity, from dystopian flooded landscapes to sterile corporate boardrooms. He has courted controversy with his subversion of taste, from €2,000 versions of IKEA bags to the now-infamous luxury “trash pouch.” His critics call him cynical, his defenders call him visionary. The truth is, he is both.

This is where his work intersects with the great traditions of avant-garde art and philosophy. Demna’s approach to fashion echoes the ethos of Dadaism—a movement born in response to World War I’s devastation, rejecting aesthetic norms in favor of absurdity and provocation. His deconstruction of clothing recalls Derrida’s concept of différance: a refusal to settle on fixed meanings, always playing between subversion and homage. And like Guy Debord’s Situationist critique of capitalism, Demna turns fashion into a stage for social commentary, selling us the very mechanisms of consumerism that he exposes as hollow.

But where does irony end and complicity begin? When Balenciaga’s distressed sneakers sell for $1,850, is Demna critiquing the absurdity of wealth, or merely cashing in on it? When he appropriates the aesthetics of poverty, is he challenging the system or profiting from its spectacle? This tension—between rebellion and profit, between critique and participation—is what makes Demna both the most celebrated and the most controversial designer of our time.

Georgian Roots, French Recognition

Despite his meteoric rise, Demna’s relationship with Georgia remains fraught. While his work frequently references his homeland—Soviet school uniforms, Georgian script, Orthodox crosses—he rarely visits, estranged from parts of his family due to his sexuality. In a country where LGBTQ+ rights remain a battleground, Demna’s global success is viewed with both admiration and unease.

Yet his Georgian identity is impossible to untangle from his work. His love for exaggerated proportions can be traced back to the Soviet aesthetics of his childhood. His rejection of conventional glamour mirrors the raw, pragmatic fashion of Tbilisi’s street markets. Even his Balenciaga couture—often austere, monastic, almost Byzantine—carries echoes of Georgia’s ancient ecclesiastical traditions.

France’s recognition of Demna, then, is layered with meaning. It is not just an award for a designer but an acknowledgment of how exile and displacement shape art. The child who fled Abkhazia now stands at the heart of European culture, receiving one of its highest honors. But is it a homecoming, or just another station in the life of a perpetual outsider?

What Happens When the Revolution Wins?

The Ordre des Arts et des Lettres was once awarded to Yves Saint Laurent, a designer who revolutionized fashion by putting women in tuxedos and making haute couture political. Today, it is pinned to Demna’s torn T-shirt—a sign that fashion’s hierarchy has shifted. The very man who turned the fashion industry upside down is now its most powerful figure.

But what happens when the rebel becomes the establishment? Can Demna still be an outsider when he sits atop one of fashion’s most elite institutions? Or has he succeeded in bending the institution to his will?

One thing is certain: Demna has not lost his ability to provoke. By accepting the award in a ripped T-shirt, he reminds us that fashion, at its most powerful, is never just about clothing: it is about symbols, contradictions, and the narratives we construct about who belongs where. And in that sense, Demna remains fashion’s greatest disruptor—even when the establishment pins a medal on his chest.

By Ivan Nechaev