In the heart of Old Tbilisi, tucked away on Leo Kiacheli Street, stands a building that is a portrait of the city itself. The Elene Akhvlediani House Museum is not just a tribute to one of Georgia’s most celebrated painters; it is a microcosm of Tbilisi’s artistic, political, and social transformations.

Unlike grand museums that monumentalize art in the cold silence of white walls, Akhvlediani’s home preserves art in its most organic form—a lived-in space. This house once buzzed with the voices of poets, composers, and avant-garde intellectuals, forming a nucleus of Georgia’s artistic resistance. Today, it continues to breathe, serving as a bridge between past and present, between artistic expression and the turbulent currents of history.

To understand the significance of the museum, one must first understand Elene Akhvlediani (1901–1975) herself. A woman who defied artistic conventions, she painted Tbilisi not as a postcard-perfect vision, but as a living, breathing entity—full of cracks, rhythms, and whispers. Her cityscapes, with their fluid lines and dreamlike hues, capture the essence of Tbilisi not as an architectural ensemble, but as a psychological space.

Trained in Paris in the 1920s, Akhvlediani returned to Georgia carrying the echoes of modernist Europe in her brushstrokes. But she did not merely imitate Western trends; she translated them into a Georgian language of form and light. Her work straddled the line between impressionism, expressionism, and the emotional essence of Georgian folk art.

What makes Akhvlediani’s legacy politically and socially charged is that she painted at a time when Socialist Realism sought to impose its rigid doctrine on Soviet art. While official art glorified factory workers and collective farms, Akhvlediani painted Tbilisi’s crooked streets, decaying balconies, and the intimate poetry of its everyday life. In a sense, her art was an act of quiet defiance, an insistence on the primacy of individual vision over collective ideology.

Akhvlediani was one of the very few female artists in the early Soviet period who achieved recognition in a male-dominated field. This alone makes the museum an important landmark in the history of Georgian feminism. Her career challenged the traditional roles expected of women at the time: she was neither a homemaker nor an artist confined to decorative crafts, but a painter of vast, ambitious urban landscapes.

Yet, paradoxically, despite her immense contributions, Akhvlediani’s place in public memory remains overshadowed by male counterparts like Lado Gudiashvili and David Kakabadze. The existence of her museum is an ongoing political act of reclaiming space for women in Georgia’s cultural history. It ensures that she is not relegated to a footnote but remains a central figure in Tbilisi’s artistic narrative.

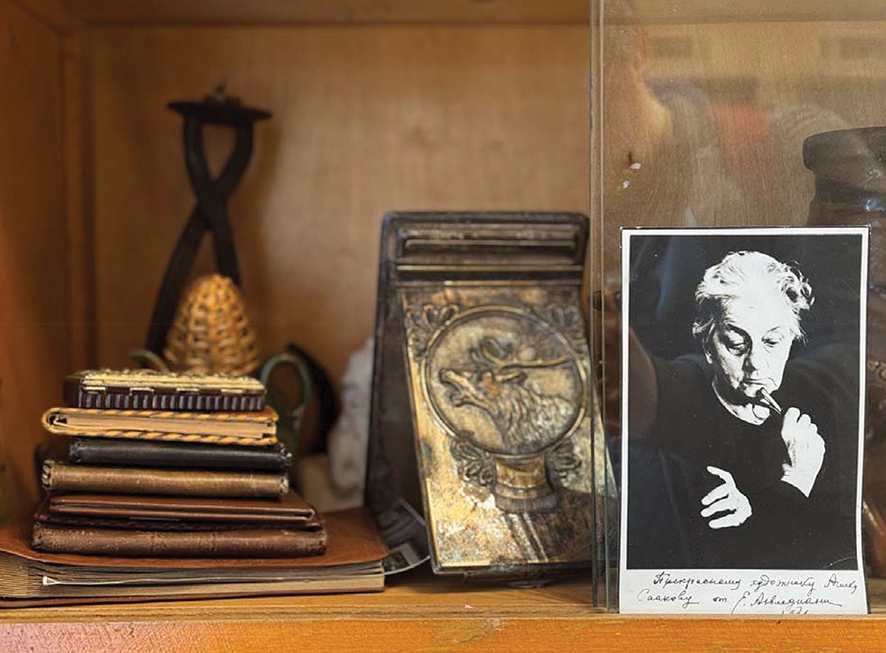

The museum, which was Akhvlediani’s actual home and studio, preserves the spirit of artistic resistance that defined her life. In Soviet times, when free thought was policed and creativity was expected to serve the state, Akhvlediani’s house functioned as a safe haven for intellectuals.

Her salon gatherings were attended by poets like Paolo Iashvili and Titsian Tabidze, musicians like Otar Taktakishvili, and theater directors who sought to push the boundaries of their craft. These meetings were more than social occasions: they were covert acts of cultural resistance, where artistic innovation was nurtured in defiance of totalitarian aesthetics.

Even after Stalin’s purges devastated Georgia’s artistic community in the 1930s, Akhvlediani’s house remained a sanctuary. This makes the museum not just a static exhibition space but a living archive of Georgia’s intellectual resilience. Today, when one walks through its rooms, one is not merely observing paintings on the wall, one is stepping into a historical moment, into the very fabric of an alternative artistic history that refused to be erased.

Established in 1976, one year after Akhvlediani’s death, the museum is more than a collection of paintings; it is a space that embodies the tension between preservation and transformation, a tension that has defined Georgian culture for centuries.

Akhvlediani’s paintings serve as a visual diary of a disappearing city. The wooden balconies, crooked alleyways, and hidden courtyards she depicted are vanishing under the pressures of gentrification and modernization. In this sense, the museum functions as a time capsule, reminding visitors of a Tbilisi that once was—a city where art and daily life were intimately intertwined. But does the museum merely preserve a romanticized past, or does it push us to engage with the city’s present and future? This is the central question that lingers in its halls.

While the museum does not explicitly present itself as a political space, its very existence is an act of resistance. Akhvlediani lived through the Soviet cultural machine, which sought to control artistic production. Yet, her work remained defiantly Georgian, her landscapes did not adhere to Socialist Realism, and her focus on Georgia’s unique architecture and landscapes subtly rejected Soviet homogenization. In this way, the museum stands as a quiet protest against cultural erasure. It tells a story that Soviet history books often overlooked: the endurance of Georgia’s artistic identity despite political pressures.

A House That Still Belongs to the Artists

In 2024, the museum underwent a significant restoration, funded by the Georgian Ministry of Culture and Sports. The project included improvements to climate control, lighting, and structural integrity. Over 100 artworks were restored, and the interior was carefully reconstructed to reflect the atmosphere of Akhvlediani’s lifetime.

In an era where gentrification threatens to erase the historical texture of Tbilisi, Akhvlediani’s house stands as a monument to the city’s artistic DNA. Tbilisi has undergone rapid transformations—glass skyscrapers replace old Soviet structures, and hip cafés take over historic neighborhoods. Amidst this whirlwind of change, the Akhvlediani Museum serves as an anchor, a reminder that Tbilisi’s identity is not built on commercialized nostalgia, but on its true artistic past.

Furthermore, the museum’s potential role as an active cultural space, hosting exhibitions, literary evenings, and experimental performances, ensures that it remains a site of creative dialogue rather than a mere mausoleum. This is what differentiates it from conventional house museums that preserve artifacts without engaging with contemporary culture.

The Elene Akhvlediani House Museum is more than a tribute to a single painter. It is a testament to the enduring power of artistic defiance, a space where Tbilisi’s past, present, and future collide. It reminds us that art is not only about beauty, it is about memory, resistance, and the refusal to conform. As long as its doors remain open, it will continue to whisper the stories of those who once gathered here, ensuring that Tbilisi’s creative spirit never fades into silence.

By Ivan Nechaev