After a months-long silence that mirrored Georgia’s own uneasy winter — marked by protests against police brutality, disillusionment with electoral outcomes, and the freeze of Euro-integration hopes — the DOCA Film Club has reemerged with a quietly incendiary response: a documentary program titled Spring. But unlike the buds of spring in nature, this season’s bloom comes not from warmth, but from pressure — the kind that builds up under regimes of surveillance, violence, climate despair, and ideological warfare.

DOCA’s Spring is not just a screening series. It is a cultural intervention that interrogates the social architectures of power and resistance. These are not films that ask you to “watch and feel.” They ask you to listen, question, and choose sides. From Beijing to Khartoum, from Tehran to the American Midwest — The DOCA Film Club’s new program, fully subtitled in English, explores the anatomy of protest, trust, and transformation through the lens of global documentary filmmaking.

The Specter of Surveillance: “Total Trust” and the Post-Private World

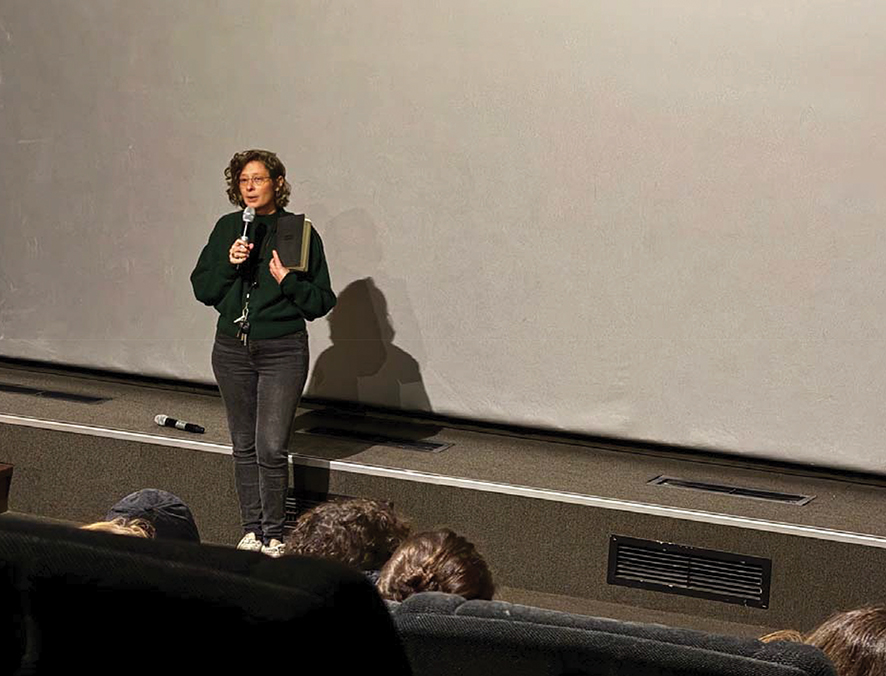

The Spring program officially began on April 14, 2025, with the screening of Zhang Jialing’s Total Trust — a documentary that can only be described as a quiet detonation. The audience at Amirani Cinema watched in tense silence as the film peeled back the layers of modern authoritarianism, revealing the terrifying intimacy of digital control. The film does not rely on abstract warnings or distant predictions — it presents lived experience. We meet women whose every move is tracked; activists whose phones become instruments of harassment; citizens who wake up to find their digital social credit scores erased, their existence algorithmically undone. What Total Trust shows is that surveillance is not just a form of watching — it is a form of writing people into silence.

In many ways, the film functions like a cinematic companion to Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, but here, surveillance is not driven by consumerism — it is deeply state-driven, culturally normalized, and enforced with surgical precision. There is no place for error, no space for ambiguity. To dissent is not to speak against power; it is to disappear from the space of the visible.

Importantly, Total Trust does not stop at diagnosis. It also quietly documents micro-acts of resistance: encrypted conversations, clandestine support groups, and children being taught how to avoid facial recognition software. These are not dramatic protests. They are subtle refusals — the kind of disobedience James C. Scott called “the weapons of the weak.” By opening the Spring program with this film, DOCA Film Club redefined the stakes. This is not merely a program about injustice. It is about the architecture of modern control and the fragile infrastructures of resistance that still remain.

After the analytical and emotional weight of Total Trust, the remaining films in the Spring program will continue this exploration of how systems of power infiltrate the most intimate parts of life: from the family home to the protest camp, from legislative bodies to emotional relationships. Each Monday in May, the Spring series will continue to unfold like a political map of contemporary resistance: in France, Monopoly of Violence (May 12) asks whether the state can ever justify force; in Sudan, Madaniya (May 19) traces the hopeful rhythms of youth-led revolution. And in the upcoming American film Evidence, the battlefield becomes ideological, as dark money and family values collide in the most personal way imaginable.

Domestic Ideologies: “Evidence” and the Logic of Dark Money

If Total Trust exposes external surveillance, Evidence (2025, USA) investigates internal colonization — how ideologies creep into family dynamics and personal identities. By connecting “dark money” politics to the beliefs of families and communities, this film offers a poignant reflection on what Antonio Gramsci called cultural hegemony — the invisible dominance of ruling-class ideologies over everyday life.

It’s not just about billionaires buying elections. It’s about how neoliberal individualism and conservative values reframe care, kinship, and civic duty in the service of empire. Through an intimate lens, the film repositions American conservatism not as political preference but as a carefully engineered ecosystem.

Paranoia and Patriarchy: “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” and the Fragility of Power

Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig is a masterclass in portraying the corrosion of trust within the domestic space under political duress. Here, resistance is not only seen in the streets, but also within the walls of a Tehran household, where a father’s moral and ideological collapse mirrors a nation’s crisis of conscience.

Anthropologists studying Iran have long pointed to the family as a contested site between state and citizen. Rasoulof stages this beautifully: a judge begins to suspect his own daughters of betrayal, transforming the father into a miniature authoritarian. The loss of his weapon becomes a metaphor — he has lost control, and what remains is fear.

This is not only a story about Iran. It resonates with philosopher Michel Foucault’s theories of bio-power: the regulation of life through institutions like the family, the court, and the state. When trust collapses within these structures, so too does the legitimacy of governance.

Ecology of Protest: “Stick Together” and the Ethics of Climate Resistance

Stick Together (Germany, 2023) trades talking heads for handheld honesty. By immersing us in the lives of climate activists, it offers an anthropology of modern protest: its exhaustion, its digital choreography, and its emotional labor.

The film implicitly dialogues with Bruno Latour’s concept of “political ecology” — that climate change is not only about the planet, but about redefining democracy. These young activists are not just protecting trees. They are protesting an epistemology — the capitalist logic that renders ecosystems disposable.

Their resistance is embodied, nonlinear, and often improvisational. This is not the idealistic protest of 1968. This is protest in the age of burnout, where commitment is measured in court summons and collective therapy.

State Violence and Its Mirrors: “Monopoly of Violence” and the Ambiguity of Force

David Dufresne’s Monopoly of Violence (France, 2020) poses a brutal question: Who polices the police? Through a non-linear editing style that juxtaposes civilian and police testimonies and footage, the film problematizes Max Weber’s classical definition of the state — as the entity with a legitimate monopoly on violence. But legitimacy, the film suggests, is not inherited. It is contested, narrated, and performed.

This film belongs in a tradition of European political thought that includes Jacques Rancière’s concept of the “distribution of the sensible” — how the state determines what can be seen, heard, or counted as political. Here, the Yellow Vest protests become not just about wages or fuel prices, but about the right to appear as a political subject.

Revolution as Rehearsal: “Madaniya” and the Dream of Civilian Government

In Madaniya (Sudan, 2024), we’ll meet Django, Esra, and Mou’men — young people who remake resistance as creative labor. One organizes rap battles. Another leads workshops. A third mobilizes women in peripheral towns. They resist not through ideology, but through practice.

Here, the revolution is not a moment, but a process — a rehearsal of futures. Anthropologist Asef Bayat, writing on post-revolutionary Egypt, might call this “non-movements”: the everyday practices of reclaiming space and time from authoritarianism. The Sudanese call it Madaniya — civilian rule. But in this film, it becomes something deeper: a cultural ethos, an insistence on pluralism, mutuality, and dignity.

From Spectators to Participants

DOCA’s Spring is not asking its viewers to merely watch oppression unfold. It invites us to recognize that we, too, are implicated — as workers, citizens, parents, siblings, and data producers. These films are not stories from elsewhere. They are mirrors with subtitles. In a Georgian context, where the line between civic participation and political suppression is increasingly fraught, this program offers more than solidarity. It offers tools: aesthetic, ethical, and tactical. And in doing so, it restores one radical truth: resistance, before it becomes a movement, is an act of seeing.

The full program and tickets are available on the official websites of DOCA Film Club, (https://www.doca.ge/en/film-club) and at Amirani Cinema.

By Ivan Nechaev