Marjory never lost the emotive and expressive depth of Rustveli’s lines when conveying them in her native tongue

Read Part I

Read Part II

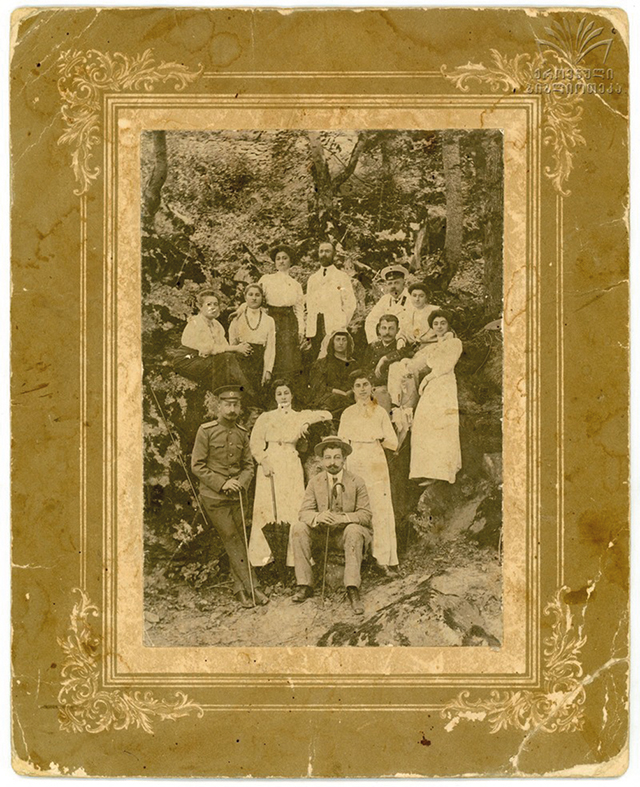

Following her departure from Georgia, Marjory plunged herself into the translation of Rustveli’s text, regularly consulting the leading experts on the topic, especially Prince Ilia Chavchavadze. Marjory was sure that her affection for Georgia was not an unrequited love and that Georgia truly embosomed her. She also well understood that the elevated welcome she had experienced in Georgia originated from the nature of the Georgian nation – artistic, generous, hospitable, inviting, and hence the abundance of exuberant metaphors and epithets or unusual similes, often skilfully presented in a hyperbolized way in Rustveli’s poem. Now, she well understood why from Tariel’s “eyes, as from a fountain, tears flowed fiercely forth; and thus there a flaming fire burned his heart” (849), or why Tinatin “condemned even the sun” (34) and when weeping, “she drooped her raven eyelashes (the tail feathers of the raven)” (46). Marjory never lost the emotive and expressive depth of Rustveli’s lines when conveying them in her native tongue. Hence comes the freshness and uniqueness of her translated version. But hyperbolic are not only the poetic lines of the poem but the life episodes that constitute the plot. It seemed obvious for Marjory that such a visualization of the world, raised to the very summit of artistic and poetic reasoning, was justified by the poet’s decision to present the story in the form of a fairy-tale. In his comments, enclosed within the publication of the poem, King Vakhtang VI emphasises and explains the reason of choosing the form of a fairy-tale, noting that Rustveli intended to assure the reader the story was not based on any real phenomena, but was created only due to his fancy, though it is a well-known fact that the poet, following the request of Queen (the King) Tamar, devoted it to her.

Marjory accepted the fantastic realm offered by the poem, and enjoyed her constant being there. More than this, she invented a fairy-tale of her own when she said no to the existing way of life, full of prejudices and restrictions, especially when her parents did not approve of her interests towards the Georgian language and literature. She went against the stream to establish special values, and nurtured them all her life. Why did she need to invent a fairy-tale of her own life? Of course, she needed it to obtain wings to reach the highest peaks and fly high in the heavens. Her fairy-tale was full of strife, endeavours and struggles, but also great joy, and by all means mercy that poured on her like snow, as Rustveli would say.

The Epilogue of “The Man in the Panther’s Skin” opens with the lines:

გასრულდა მათი ამბავი ვითა სიზმარი ღამისა.

გარდახდეს, გავლეს სოფელი, – ნახეთ სიმუხთლე ჟამისა!

Their tale is ended like a dream of the night.

They are passed away, gone beyond the world. (1572)

Like all fairy-tales Marjory’s fantastic tale had to end, and it happened on 7th December, 1909, in Bucharest, where she was staying with her diplomat brother, as always following him on a mission. Marjory died suddenly from a stroke at the age of 40. Her body was returned to England and she was buried in Sevenoaks, Kent. Her passing was mourned in Georgia as a national calamity.

She went against the stream to establish special values, and nurtured them all her life

It is obvious that from childhood, Marjory constantly had Georgia on her mind, and for a full eighteen years carried Rustaveli’s poem within her soul and body. It very much resembles bearing a child in one’s soul and body and nurturing it with love and anxiety. Marjory worked on Rustaveli’s poem until the end of her life, telling Oliver she needed ten more years to make the due refinements. Regretfully, her life ceased before she could see the accomplishment of the translated manuscript developed or published. The fragile maiden of the fairy-tale passed on when giving birth to her dear child, but it was a “child” well nursed and attended by her brother thereafter. It was Oliver who immediately established the Marjory Wardrop Fund and collection at the Bodleian Library, the University of Oxford, and “The Man in the Panther’s Skin” in Marjory’s translated version was published in the Oriental Translation Fund, New Series, volume XXI, 1912, London. The poem was preceded by Oliver Wardrop’s capacious and very rich in content Preface and followed by Marjory’s Notes and Appendices.

Shortly before the publication of the poem, Oliver, while on board a British ship sailing for Africa, met Russian poet, Konstantin Balmont. Oliver introduced the poem to the Russian poet, who expressed his impression in the most moving way: “I touched a Georgian rose in the speciousness of the ocean dawns and sunsets… wild whirlwinds and fierce storms…” Thence stemmed the first full Russian translated version of Rustaveli’s poem by Konstantin Balmont, published in Paris in 1933. It was Marjory who opened a new way to Rustaveli’s fame which resulted in over 50 translated versions of the masterpiece in numerous languages.

\The legacy of Marjory Wardrop is well taken care of and continues successful on. The British and Georgian governments agreed to announce the year 2019 as the Year of Marjory Wardrop so as to commemorate 150th Anniversary of her birth. Many important events took place in Georgia and Britain, among which a conference was held in December 2019 at the Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University which saw the launch of the Marjory Wardrop English-Georgian Dictionary, prepared by the Lexicographic Center of our Alma Mater.

Oliver’s ties with Georgia were especially strengthened in 1919, when Sir Winston Churchill proposed to him the post of the British Chief Commissioner of Transcaucasia. Oliver was most delighted to accept the offer and held the post until the Bolshevik invasion of Georgia in February 1921.

The Georgian nation immortalized the Wardrops’ contribution, and in 2015, in Tbilisi, in a tiny, lovely park, erected a monument showing Marjory and Oliver strolling there side by side. The location of the monument is on the way to Mtatsminda (Holy Mountain) with its Pantheon of Georgian Writers and Public Figures.

Continued in next week’s GT and online on georgiatoday.ge.

By Innes Merabishvili

*Innes Merabishvili is the Head of the Chair of Translatology with MA and PhD programmes at Tbilisi State University