On June 15, at Tbilisi’s Griboedov Theater, Natalia Osipova presented Force of Nature, a curated selection of classical and contemporary pieces performed alongside a cast of international dancers. The evening marked the Georgian premiere of the program and Osipova’s first performance in the country — part of the Soso Lagidze International Art Festival Tbilisi Rhythm, now an established fixture in the city’s cultural calendar.

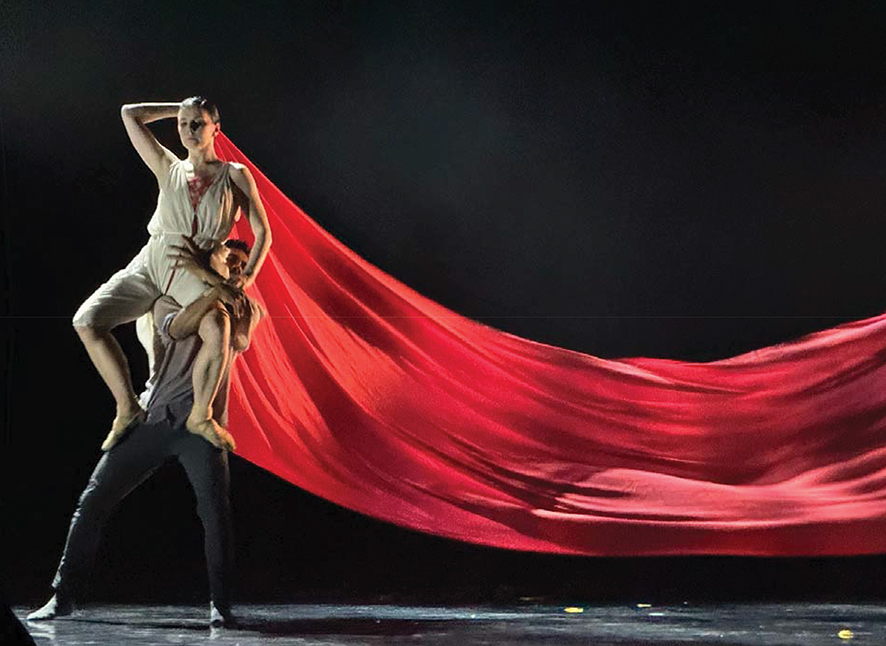

Rather than a gala performance showcasing familiar crowd-pleasers, Force of Nature offered a relatively austere proposition: a sequence of solos and duets shaped more by structural tension than theatrical flourish. The program traced a line between ballet’s codified past and its more gestural, contemporary permutations. Osipova, a principal at The Royal Ballet with an increasingly independent curatorial agenda, positioned herself at the intersection of those modes — at once channeling classical syntax and disrupting it.

She was joined onstage by a group of dancers from a wide range of stylistic and institutional backgrounds: Jason Kittelberger, choreographer and long-time collaborator; Vienna State Opera’s Victor Caixeta; English National Ballet dancers Francesca Velicu and Daniel McCormick; Mariinsky Theater’s Daria Pavlenko, also associated with Tanztheater Wuppertal; and Joseph Kudra of Sharon Eyal’s company. Rather than forming a coherent ensemble, they functioned as a rotating cast — each bringing distinct vocabulary and affect, generating a kind of curated polyphony.

The choreography, drawn from a range of sources, avoided narrative and theatricality. Instead, it leaned on spatial tension, fragmentation, and contrasts in weight and dynamics. At times, the works felt more like studies than performances — analytical rather than emotional in register.

Osipova’s physical presence remains striking, though her interest here seemed to lie in restraint rather than display. She modulated her presence to the demands of each piece: expansive in some, nearly minimal in others. She did not attempt to unify the program through a dominant persona; if anything, she worked to defer to the internal logic of each duet or solo.

The technical achievement was not in question. More pertinent was how the program resisted familiar arcs of virtuosity or romantic catharsis. The evening neither sought to overwhelm nor seduce. It was built with a kind of choreographic neutrality — rarely indulging in emotive crescendos, often retreating into ambiguity.

Osipova’s appearance in Georgia carries particular cultural resonance, not least because of the country’s significant contribution to 20th-century ballet history. She acknowledged as much in her remarks following the performance, citing names like Vakhtang Chabukiani, Nino Ananiashvili, and Irma Nioradze. Her program, however, did not attempt to directly engage with or respond to that lineage. Rather, it existed in parallel — a European project inserted into the Georgian context, without overt gestures of local reference or adaptation.

Still, the performance comes at a moment when Georgian dance institutions and audiences are reexamining their relationship with the international ballet circuit. Osipova’s project, with its curated eclecticism and controlled aesthetic framing, offered one model of what international ballet now looks like when unmoored from company affiliations and repertoire constraints.

Tbilisi Rhythm, supported by the Ministry of Culture and the Tbilisi City Hall, continues to broaden its programming beyond music into interdisciplinary and hybrid forms. This season will conclude with a concert by French accordionist Richard Galliano, suggesting an interest in contrasting sensibilities — from choreographic abstraction to lyrical improvisation.

The inclusion of Osipova’s program signals the festival’s desire to position itself within a more transnational conversation, aligning with the kind of flexible, artist-driven formats now common in European dance and performance festivals.

Force of Nature did not deliver revelations, nor did it seek to. It functioned more as an aesthetic dossier — a survey of tendencies, performed by dancers who understand their craft and can move between codes without rhetorical excess. What the Tbilisi audience received, then, was not a spectacle but a set of propositions: about movement, about authorship, and about the body as a site of curated uncertainty.

Review by Ivan Nechaev