There are few cultural spaces in Tbilisi that feel so gently alive as the Gabriadze Theater — a place where puppets breathe, clocks sigh, and the city itself seems to listen. With the launch of its new bilingual and trilingual mediation program, the theater opens an invisible threshold: an encounter between art and reflection, between performance and collective introspection. Two new mediations — The Art of Staying Human led by Chika, and Machines of Time and Mechanisms of Memory curated by Misha — now accompany the theater’s repertoire in Georgian, English, and Russian, becoming part of its permanent program and online presence.

Both mediations carry the same quiet radicalism that defines the Gabriadze ethos. They transform the theater visit into a process of thinking, feeling, and remembering. The gesture recalls the European model of artistic mediation that emerged within museums and contemporary performance institutions — yet here it finds a singular Georgian rhythm, woven from the tactile poetry of Gabriadze’s imagination.

The Art of Staying Human invites the visitor into a liminal space between spectacle and solitude. Actress and longtime collaborator Chika guides us into the intimate alcoves of the Theater. Her narration unfolds personal anecdotes of rehearsals and of mornings spent with the late founder, Rezo Gabriadze. Every puppet in that realm authorises a meditation on embodiment. Chika reveals how breath, movement and touch transform wood and fabric into characters imbued with gesture and memory. The venue becomes a terrain of anthropological inquiry: a theater of the human, where the human is refracted through the marionette’s suspended being. Chika’s narrative foregrounds the theater’s ethic: art is a human practice, and its objects (puppets, clocks, miniature settings) demand as much care as performers themselves. The visitor becomes a witness to that care, and thereby a participant in it.

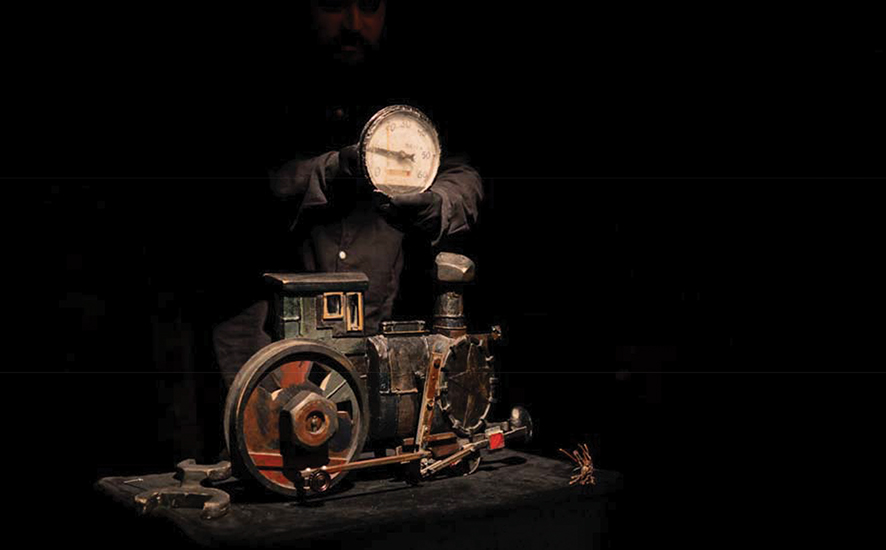

In his mediation Machines of Time and Mechanisms of Memory, actor Misha ushers us into the subterranean mechanics of the Theater’s machine-metaphor. The tour is structured in acts, each devoted to a dimension: childhood and memory; time as poetic medium; the hidden architecture of puppets; performance ritual and healing. Misha’s tone is confessional without being intimate in the conventional sense. He recounts his own memories, and from there extrapolates to a wider ontology of the haunted object. The Theater becomes a laboratory of time, where “machines breathe” and “stories carry the weight of memory.”

Here, the visitor is not simply guided, but invited into a topology of remembrance: the marionette’s joint, the clock’s hinge, the thread pulley—each becomes a site of recollection. Memory, in Misha’s framing, is not romantic, but structural. One learns how the Theater itself acts as an archive, how matter holds events. One hears the hint of psychoanalytic echo: the puppet’s stillness and the mechanism’s silence contain the shadow of what has happened, what is withheld, what persists.

These two mediation formats indicate the Gabriadze Theater’s evolution from a singular auteur-space (Rezo Gabriadze’s domain) into a reflexive cultural institution. The move signals a discursive turn: the theater invites not only spectatorship of performances but site-specific reflection on production, memory, materiality and human being. The trilingual offering breaks the monolingual mould of many Georgian cultural institutions, and thus acknowledges the multiplicity of audiences and heritages in Tbilisi’s globalizing present. These mediations stage the primacy of process over product. We are oriented away from the theatrical event as climax, and toward the theater as apparatus of being. The human remains, in Chika’s title, “the art” to be sustained; memory remains, in Misha’s axes, the construct to be attended. In both programmes the theater functions as a machine of experience, but one whose gears are wound by humility and attentiveness, rather than spectacle alone.

The Gabriadze Theater’s decision to institutionalize mediation marks a decisive step for Georgian cultural life. It signals a maturity of approach — one that treats heritage as a process of renewal and art as a tool of consciousness. Mediation here is not interpretation. The mediators are not guides but co-authors in an ongoing conversation between the audience and the theater’s spirit. In this sense, the project aligns with a broader movement across contemporary art institutions, from documenta’s discursive programs to the reflective practices of theaters like Rimini Protokoll or the Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne. Yet the Gabriadze version has an entirely different pulse. It carries the city’s melancholic humour, its post-Soviet texture, its faith in small gestures.

To attend these mediations is to enter a philosophical theater without actors, where the performance happens within the mind of the listener. It is an experiment in cultural time — an invitation to think with tenderness. The Gabriadze Theater once taught the world how puppets can feel more human than people; now it teaches how memory itself can perform, how humanity can be curated as an art form.

By Ivan Nechaev