In an age where cultural memory is often digitized, repackaged, or abandoned altogether, the gala evening held on May 29 at the Tbilisi Concert Hall stood as a state-scale ritual; a kinetic liturgy, a celebration of the living mythos that is Gelodi Potskhishvili. At 80, the legendary choreographer was honored not with words but with bodies—those of his dancers, his heirs, and his prodigies—moving across the stage in an act of reverence that fused nationhood and narrative, war dance and tenderness, classical precision and folkloric fire.

The evening, co-curated by Gela Potskhishvili and Maia Kiknadze, bore the weight of lineage and legend. But it was Giorgi Potskhishvili—the choreographer’s grandson and a soloist of the Dutch National Ballet—who emerged as the embodied axis of generational continuity and global acclaim. When Giorgi leaped into the air, it was as if the history of Georgian movement had been hurled into the future.

Where Time Dances in Circles

The program opened with the Colchian Suite, originally choreographed by Gelodi in 1978 and reimagined by Gela. It was a fitting prologue: ancient, elemental, structured like a sun ritual for an ancestral theater.

The signature of the elder Potskhishvili—his orchestration of space, the geometrical rigor of his choreographic syntax—remained intact, but the younger Gela’s touch added an architectural dynamism. Dancers emerged like bronze-age spirits in ceremonial motion.

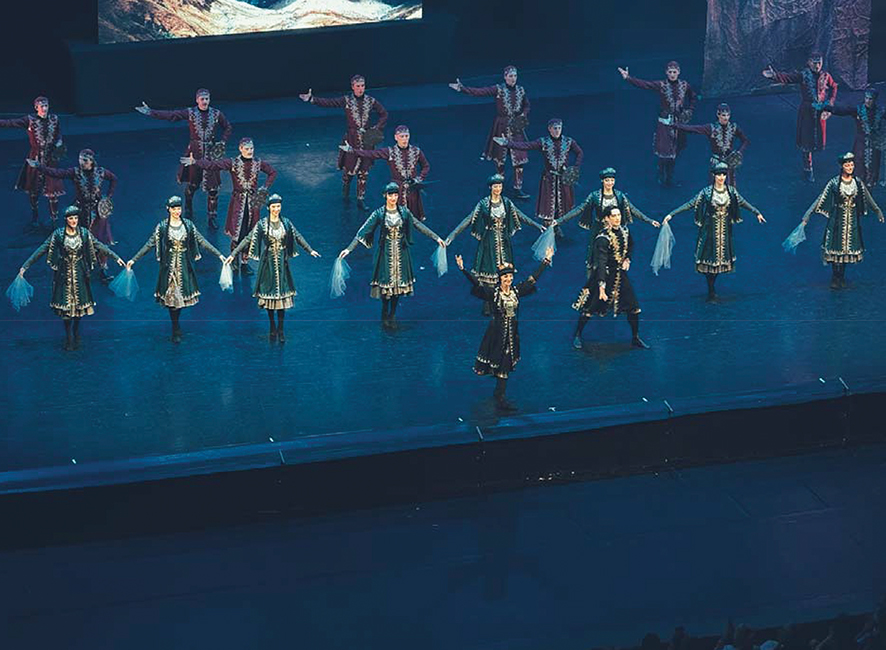

The progression through Samaia, Davluri, and Khorumi was a lesson in the codification of identity through dance. These are not folkloric footnotes. These are national myths inscribed in muscle memory. In Khorumi, with its primal, battle-rooted rhythm, the National Ballet of Georgia delivered a breath-snatching study in collective masculinity—flinty, furrowed, and fanatically disciplined.

But then came Atabe, the Khevsurian solo danced by Giorgi Potskhishvili himself. What can one say of a moment when lineage meets virtuosity so raw it seems not danced but channeled? The Khevsurian style—with its sharp, sword-edge leaps and hyper-masculine theatricality—was transformed in Giorgi’s hands into a high-modernist lament. Here was the mountainous past reconfigured by an Amsterdam-trained soul. Giorgi did not merely inherit; he transfigured.

The women were not sidelined in this monument to Georgian masculinity. The Women’s Mtiuluri reminded the audience that mountain dances, though often imagined as male domains, carry a quiet violence when interpreted through the feminine. Parikaoba—the swordsmanship duet with Giorgi—was a tragic eroticism rarely seen in nationalist dance. Steel met silk. Sparks flew, literally and choreographically.

Global Echoes and Ballet Diplomacy

Where the first half was mythic and local, the second act broadened into a choreography of diplomacy. This was Georgia dancing with the world, not for it.

The “Old Tbilisi Suite” brought the city’s ghost streets to life. It was nostalgia engineered with balletic clarity—tiled roofs turned to spinning pirouettes, balconies into arched arabesques. Then the curtain lifted for Minkus’ Don Quixote pas de deux, danced by Anna Tsygankova and Giorgi Potskhishvili. Their chemistry was incandescent. Anna, the prima of the Dutch National Ballet, was fire-tipped elegance, her extensions like flourishes in calligraphy. Giorgi, again, moved with weightless muscularity, bridging folk grounding with imperial classicism.

Jeirani, Trick of Riders, and Imeretian Dance followed—each a showcase of Gela’s interpretive retooling of Gelodi’s legacy. These works are no longer historical artifacts; they are transnational kinetic vocabularies. Gela Potskhishvili’s choreographic direction does what few can do: preserve without embalming, innovate without desecrating.

Then came The Dying Swan. Tsygankova danced it with wrenching intimacy, her arms liquid, her decay celestial. In the hands of this gala, Saint-Saëns’ elegy was no longer a solo but a farewell to time itself.

The gala climaxed with Mkhedruli (Warrior’s Dance) and the Final Dance, both choreographed (or re-choreographed) by Gela. These were not simple crowd-pleasers but explosive declarations of identity. With stage pyrotechnics igniting each climactic beat, the choreography detonated across time and place. The body was both archive and prophecy.

Giorgi and Gelodi: Between Dynasty and Destiny

The story of Giorgi’s rise often circles around biography: son and grandson of Georgian ballet royalty, graduate of European institutions, soloist in the Dutch National Ballet. These facts carry weight. But on stage, Giorgi never dances to confirm a legacy. He expands it. His arms contain echoes of Parisian lyricism, his feet the unforgiving geometry of Vaganova school, and his chest the anchored breath of mountain rituals. Every plié becomes a descent into ancestral earth. Every leap draws a new map in the air.

On that stage in Tbilisi Concert Hall, surrounded by the National Ballet founded by his family, Giorgi occupied a space far beyond stardom. His solos in Atabe and Don Quixote became case studies in physical rhetoric. In Atabe, the Khevsurian warrior turned philosopher. Giorgi transformed the dance’s explosive syntax into a study in held tension and interiority. Without forcing a narrative, he revealed the story of a body trained in survival, ceremony, and style.

His work with Anna Tsygankova in the Minkus pas de deux revealed another facet. Precision moved alongside seduction, and balance became a duet with gravity. In those moments, Giorgi appeared as an artist in complete control of his physics and his mythology. Their performance did not borrow emotional force from familiarity. It constructed its own register—elegant, attentive, and utterly convincing.

To witness Giorgi in performance is to see tradition realigned with velocity. Georgian choreography, under his interpretation, becomes a kinetic philosophy—fierce but deliberate, lyrical but muscular. While many artists spend their careers searching for a language, Giorgi has inherited one already rich with metaphor, discipline, and historical charge. What sets him apart is the way he inscribes his own syntax into that vocabulary. In this moment—between generations, between genres, between nations—Giorgi Potskhishvili is revisiting a golden past and engraving a future in real time. One pirouette at a time.

By Ivan Nechaev