On a bright afternoon in Tbilisi, the Radisson Blu Iveria Hotel does what international hotels do: it offers an air-conditioned lobby, the faint smell of expensive cleaning products, and the invisible hum of transient business. But climb the stairs to the exhibition passage, and the space seems to fold in on itself. The temperature is the same, but the light changes, and suddenly you’re standing in Zurab Abkhazi’s universe — black, white, textured, deliberate.

The show is called Celestial Bodies, though the word “celestial” is almost misleading. The work is less about heaven than about the long, slow tactility of space, the kind you can almost run your fingers along.

Abkhazi was born in Gori in 1968, studied at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, and spent years teaching art in Uplistsikhe — the ancient rock-hewn town where cave walls hold both prehistoric carvings and Soviet graffiti. It’s the kind of place where you understand, viscerally, that history is not a sequence, but a compression. From that vantage, his paintings make sense. He is a German Expressionist in temperament — broad gestures, heavy surfaces — but his pigments carry the weight of stone dust.

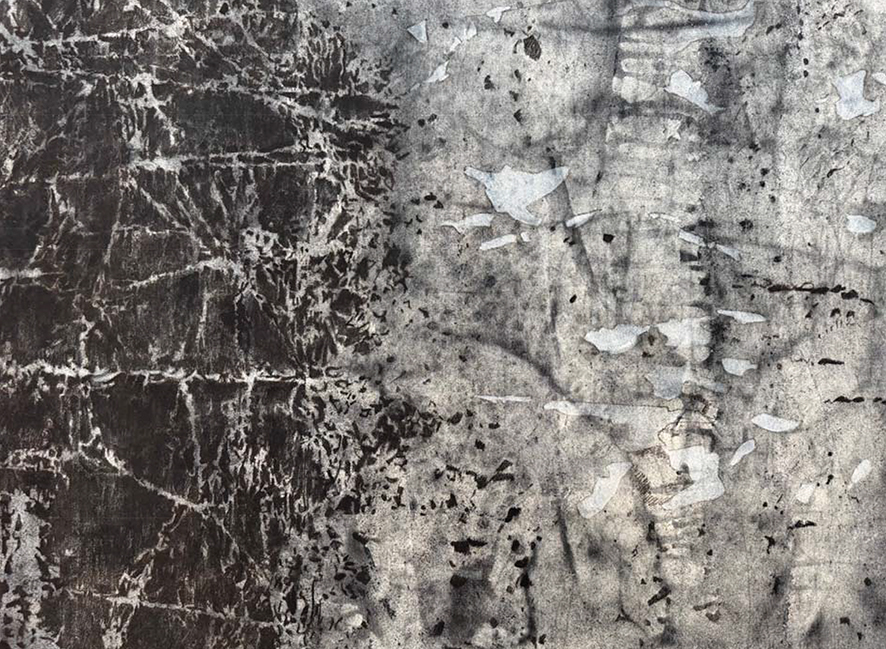

The show, presented by Dédicace’s Gallery and Silk Hospitality, comes with the claim that “the endless combinations of black and white mirror the cosmos itself, mysterious, infinite.” In the hands of another artist, this might land as just the usual marketing breathlessness. But Abkhazi’s monochrome isn’t minimalism; it’s geology under a telescope. His blacks are not voids but sediment. His whites have weight. They don’t float — they press down.

One of the works in Celestial Bodies doesn’t announce itself. It’s modest in scale, hung low, as if it had slipped into the exhibition by mistake. It looks at first like an aerial photograph of tundra in winter — patches of pale terrain, rivers of black cutting through. But stand there for more than a minute and something happens. The pale becomes luminous, the black begins to curl inward, and the whole surface starts to feel less like land than like the skin of a planet seen from an impossible closeness.

The shift is partly optical, partly narrative. In anthropology, there’s a term — “scale-switching” — used to describe how people move between the intimate and the monumental without warning. A villager speaks about the family cow and, without a pause, about the fate of the nation. In Georgian culture, this leap is instinctive: a supra table conversation can start with the texture of the wine and arrive, two toasts later, at the nature of the universe. Abkhazi’s painting works the same way. You think you’re looking at mineral pigment; then you realize you’re looking at time itself, pressed flat.

And because the show is happening in the Radisson Blu, there’s another layer. The room hums faintly with the air-conditioning; someone in a suit drifts by, checking their phone. In Erving Goffman’s sociology of “frame analysis,” such interruptions are called “key changes” — the moment the scene you’re in is redefined by an external cue. You’re orbiting the painting, and then you’re pulled back into the gravitational field of the hotel, where infinity is measured in Wi‑Fi signal strength.

In the centuries when the Silk Road cut through this part of the Caucasus, travelers stopped at caravanserais — stone inns built around courtyards — where merchants, pilgrims, and envoys from far-off cities shared walls, meals, and the occasional rumor about empires rising or collapsing beyond the horizon. Today, the Radisson Blu Iveria stands on the same trade routes, though the currency has shifted from silk to conference calls, the camel bells replaced by the discreet click of wheeled suitcases.

Still, the exhibition hall feels like a descendant of those older waystations. Business travelers in pressed shirts wander in with the vague curiosity of people between obligations. A pair of tourists in sandals linger longer, speaking French to each other in hushed tones. A Georgian couple, here for a wedding reception downstairs, stumble upon Abkhazi’s paintings as if on an unplanned detour. The room becomes a shared pause, a modern courtyard without walls.

Anthropologists might call this a “contact zone,” borrowing Mary Louise Pratt’s term for spaces where cultures meet under asymmetrical conditions. But here, the asymmetry isn’t political — it’s temporal. The hotel runs on the schedule of flights, check-in times, and corporate agendas; the paintings operate on geological time, cosmic time. In the brief overlap, a traveler might carry something away that can’t be scanned at security: the memory of a pigment’s shadow, the sense of walking between stone and void.

Outside, Tbilisi’s traffic pushes east and west along Rustaveli Avenue, tracing the same axis that once ferried silk, spices, manuscripts. Inside, under the steady hum of the air system, Abkhazi’s Celestial Bodies holds its ground like a small planet in a high-velocity orbit — and for those who step inside, the journey briefly changes direction.

Review by Ivan Nechaev