Tbilisi has a gift for turning thresholds into rooms. Streets slip from Ottoman balconies into Soviet courtyards; a single stairwell can feel like a hinge between centuries. The newly opened Anagi Art Foundation steps directly into this Georgian habit of standing on the threshold and making it habitable. It is less a building than an argument: that art made in a so-called “transitional” era is not a footnote to the present, but its grammar; that an archive can perform like a stage; that a shop might double as a research engine; and that the most honest way to speak about “after” is to show the seams of “during.”

The Foundation’s program opens with a multi-part exhibition ecology, whose keystone is Fragments of Transition—a research-driven reconstruction and re-interpretation of the late-Soviet and early-independence years in Georgian art. Orbiting it are three exhibitions that together act like instruments in a quartet: a photographic archaeology of Sergei Parajanov’s Legend of Surami Fortress; the conceptual, technically restless practice of Giorgi Shengelia; and a long-overdue encounter with Gregor Danelian, the Tbilisi-Armenian painter whose caprices read today as both nonconformist testimony and formalist manifesto. A fourth chamber—devoted to Sergo Kobuladze—is an archive staged as cosmology, a model for what the Foundation seems to want to be: a house of memory that refuses to fossilize.

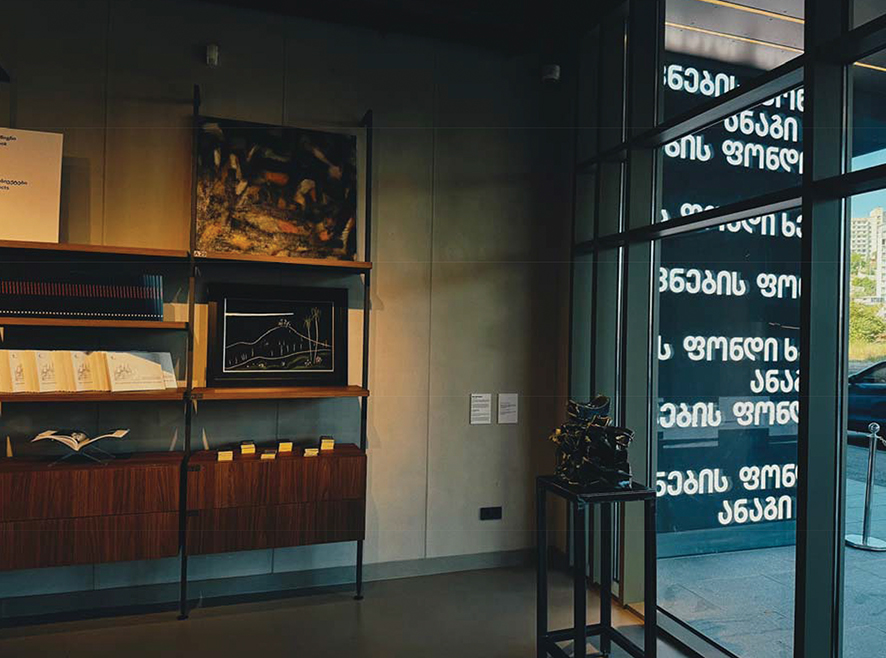

If the show is a thesis, its abstract is the Foundation’s own structure. Anagi is a private initiative designed, as its founders put it, to braid business with art and reinvest revenue into conservation, research, and public programs. The Art Concept Gallery—a curated emporium of numbered objects, limited editions, and exhibition-driven goods—gives that promise concrete form. You take something home and, in theory, fund the next question. There are precedents for this in global museum culture, but in Georgia—where the institutional landscape has historically been either starved or centralized—the model reads less like retail and more like a wager: can a shop behave like a bibliography?

The exhibition that remembers the present

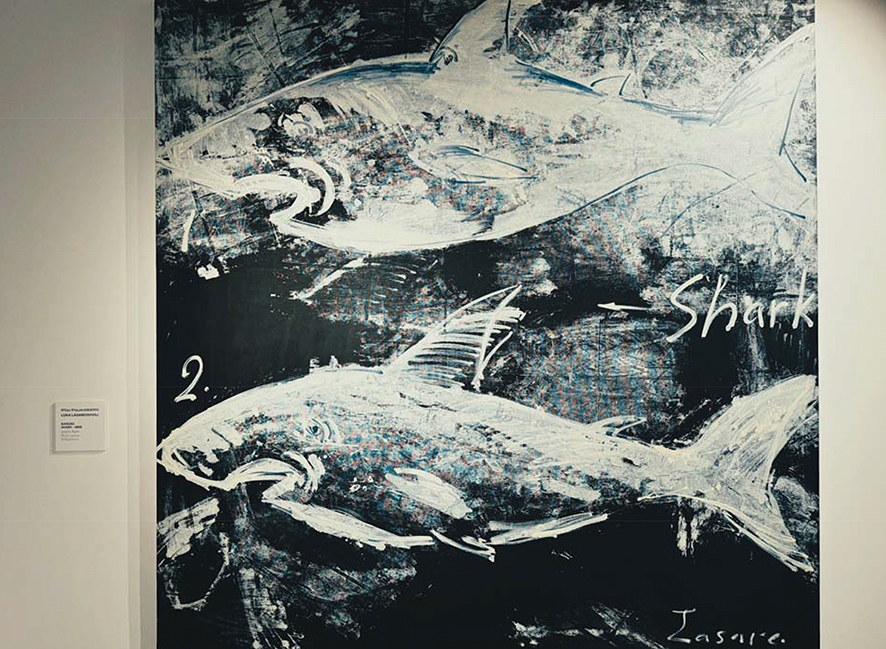

Curated by Thea Goguadze-Apfel with research by Mariam Shergelashvili, Fragments of Transition does something crucial: it refuses to treat the late 1980s and early 1990s as a tidy prelude. Instead, it reads the period as an ongoing structure of feeling. The exhibition assembles works by Luka Lasareishvili, Iliko Zautashvili, Alexander Bandzeladze, Akaki (Koka) Ramishvili, Mamuka Japharidze, Guela Tsuladze, and Gia Rigava, alongside archival material for Gia Edzgveradze—a roster that not only maps an art scene but revives the specific pressure system under which it formed: Perestroika’s permissive fractures and the first years of Georgian independence, when state structures destabilized faster than new institutions could congeal.

This is not, however, a generic “post-Soviet” sampler. The curatorial frame explicitly reconstructs two historically formative exhibitions in Germany—Georgia On My Mind (1990, DuMont Kunsthalle, with the Fridericianum and documenta Kassel) and Ein Dialog (1994, organized by the German gallerist and collector Françoise Friedrich). Those shows were not merely export events; they reframed Georgian contemporary art as a participant—rather than an exception—in the debates of the day. The catalogue writing of the period (Boris Groys among them) argued against a folkloric reading of “national schools,” proposing instead that artists in the 1990s negotiated between local memory and transnational codes, neither fully “Eastern” nor subsumed by the homogenizing vocabulary of global contemporaneity.

Fragments of Transition operationalizes that discourse. It doesn’t nostalgically rehang the past; it reactivates its questions.

One of the exhibition’s most vivid case studies is the dialogue between Mamuka Tsetskhladze and Karlo Kacharava—friends, collaborators, and members of artist formations like Archivarius (1984), 10th Floor (1986), and the Marjanishvili Studio (1987). Their work is reunited here largely through the stewardship of Friedrich’s collection, which kept crucial pieces intact and legible as a constellation.

The tiger who walked out of the frame

Tsetskhladze’s monumental Tiger (1988), painted in Tbilisi and shown that year in a UNESCO space in Paris before its long absence from home, bears the genetics of neo-expressionism—saturated color, muscular brushwork, figuration punched through by abstraction. But the painting is more than a style citation. The tiger’s body is assured while its mask-like face looks startled, as if mid-metamorphosis. The animal appears to breach the picture plane, to enter the viewer’s space with an authority that its gaze cannot quite cash. That dissonance—confident motion, bewildered attention—becomes an allegory for a society stepping out of one regime and into something unnamed. In Kacharava’s terms, Tsetskhladze articulated a notion of “Rich Art”: work that, precisely because it resists the utilitarian logic of its environment—non-commercial, impractical, excessive in scale—claims a different kind of value.

The diary that learned to paint

If Tsetskhladze gives the transition a body, Kacharava gives it a syntax. Painter, poet, critic, he wrote the era as he painted it—on diary pages, on German and Russian newspapers, on whatever support came to hand—and nearly always with a dedication: FÜR someone, named and beloved or canonically distant (Clemente, Kiefer, Baselitz, Duras). This habit of address matters. It inserts intimacy into art history, making influence feel like correspondence rather than capitulation. Kacharava’s surfaces are famously saturated—image, text, a pasted train ticket from his 1991 stay in Germany—so that the ground never disappears into neutrality. He wants the background to retain its own “history,” to be read as time and place as much as pigment. The result is a palimpsest that refuses clean beginnings, a visual essay in which the line and the sentence negotiate for breath. If painting is often accused of silence, Kacharava counter-accuses with chatter, and the chatter is learned, tender, and structurally restless.

As a pairing, Tsetskhladze and Kacharava anchor the show’s claim: transition is not a bridge you cross; it is the very condition of walking. Their works, made at the edge of a state and in the interior of a friendship, naturalize hybridity without surrendering specificity.

East/West is not a compass, it’s a tension

The larger Fragments constellation extends that argument across practices that, at the time, invented new forms under pressure: conceptual strategies, experimental media, and political commentary as tactics suited to a ground that kept moving. Seeing these works in Tbilisi, many for the first time, matters. It breaks a familiar circuit in which the archive of Georgian contemporaneity lives abroad and is accessed as rumor. Here, the rumor becomes room.

Françoise Friedrich’s role is not incidental. Collections shape art history by sustaining ensembles that markets tend to atomize. In this case, the collection has functioned as both conservator and interlocutor, preserving not just individual works but the dialogue between them. Reintroducing that dialogue in Georgia is an institutional act with theoretical stakes: it suggests that the country’s “transition” is not merely toward European structures, but toward custodianship of its own contemporary archive.

Cinema as archaeology: the Parajanov room

The exhibition devoted to Sergei Parajanov’s Legend of Surami Fortress (1984) takes a deliberately oblique angle: not a film screening but a suite of photographs from the 1985 production—anonymously shot, preserved in a private collection, and presented here by Fotoatelier as a “visual historiography.” That phrase sounds like a funding proposal until you’re in front of the pictures. Then it becomes literal. The images have the procedural clarity of documentation and the composed intensity of tableaux; they are at once notes and myths, the grammar of Parajanov’s ritualistic directing method caught in full breath.

Parajanov’s detour from socialist realism is already canon—the non-linear montage, the liturgical symbolism, the story told as a cascade of images that behave more like illuminated manuscript than cinema. What the photographs add is a view of collaboration as liturgy. We see mise-en-scène not as decoration but as ontology; props act like actors; the set is a theology of space. The curatorial idea of the anonymous gaze is more than a clever conceit. It reframes authorship, reminding us that the “aura” (to borrow from Benjamin) of Parajanov’s cinema is a labor of many hands, and that still photography can do more than archive—it can make meaning at a different shutter speed. The film’s legendary theme—the boy entombed in the fortress wall so that the structure might stand—becomes, in the photos, a metaphor for the way cultural memory embeds sacrifice into beauty, and the way images entomb time so that our edifices of understanding don’t collapse.

Accident as method: Giorgi Shengelia

Giorgi Shengelia’s exhibition threads together two essential bodies of work—Accidental Portraits and Untitled Sheets—to argue that the “accident” is not an error state but a philosophical category. Blur, distortion, and technical abrasion are not defects but tools that dilate perception, dislodging the photograph from its default documentary contract and pushing it toward a phenomenology of seeing. In these images, the line between human, animal, and landscape trembles; subject and object trade places; the print itself—its grain, its surface treatments—becomes an actor.

There is a long conversation here with the theory of photography in the late twentieth century—indexicality versus performance, the punctum that wounds and the studium that explains—but Shengelia locates those debates in practice. His training in photojournalism shadows the work; you can feel the memory of reportage in the way the camera notices. But the images aren’t after facts; they’re after duration. Instead of decisive moments, they offer decisive traces: a gesture remembered by its blur trail, a gaze that survives as atmosphere. The result is a visual ethics for a culture of estrangement—images that admit they cannot deliver certainty and, in that admission, deliver intimacy.

The capriccio as self-preservation: Gregor Danelian

The rediscovery of Gregor Danelian is one of the program’s quiet shocks. Born in 1950, trained in Tbilisi and Yerevan, Danelian sits uncomfortably—and therefore productively—inside the categories we have for late-Soviet art. “Outsider” and “nonconformist” are umbrellas that keep the rain off, but they can also flatten the weather. The show’s argument is more precise. It tracks Danelian’s chameleonic stylistic arc—Expressionism and Pop’s collage energies in the 1960s–70s; Rayonism, Cubism, and metaphysical painting in the 1970s–80s; a mystical, esoteric luminosity in later decades—without pretending that the shifts are decorative. Each turn is a survival tactic and a formal wager.

The still lifes echo de Chirico’s metaphysical stagecraft and Morandi’s devotional attention, with a local register that recalls Robert Kondakhsazov. Portraits carry the planar gravitas of Armenian fresco, the grotesque gleam of caricature, and the ethnographic precision of a gaze that refuses to exoticize even as it isolates. Family scenes organize their space as if it were woven: carpets and tapestries migrate from object to compositional logic, turning backgrounds into ornamental terrains. The term capriccio—a fantasy that assembles real fragments into invented vistas—fits not only as genre but as method: Danelian composes an equation between Tbilisi-Armenian and Western visual variables that is as local as a courtyard and as cosmopolitan as a library.

What becomes clear is that decadence, for Danelian, is not an indulgence; it is an ethics. Against a culture of ideological austerity, he insists on aesthetic plenty—on complication, on surface, on the right to ornament as thought. That insistence lands with particular force now, when moral clarity is often demanded at the expense of ambiguity. Danelian’s answer is form.

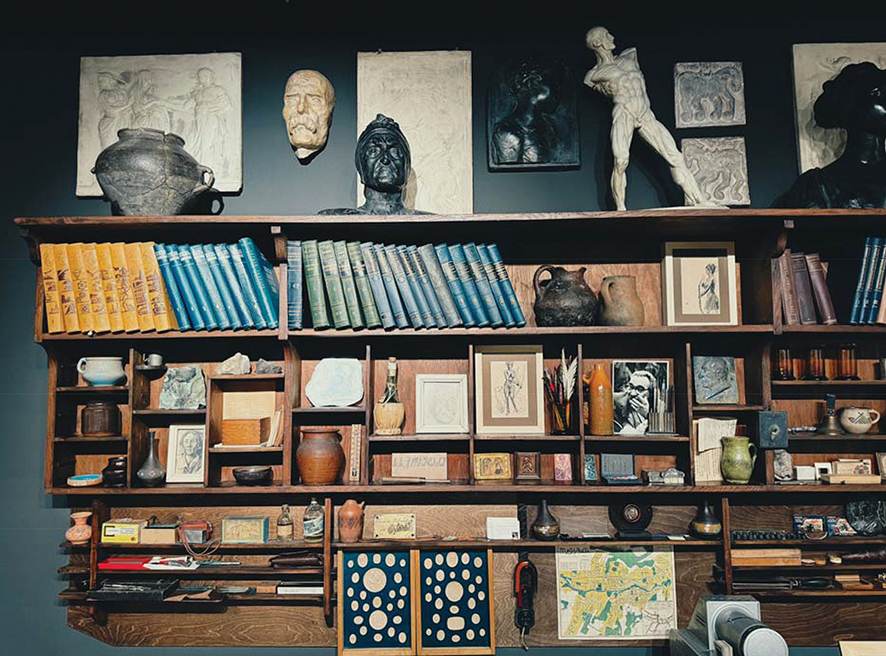

The archive that behaves like an altar: Sergo Kobuladze

Curated with a dramaturg’s ear by Thea Goguadze-Apfel, advised and scenographically tuned by Marika Rakviashvili, the Sergo Kobuladze room is the exhibition’s most explicit wager on the archival turn: the idea that archives are not storage but media. Here, the twentieth-century polymath—painter, printmaker, photographer, theorist, designer—reappears as a studio made legible. Casts and reliefs from the Renaissance and Classicism gather alongside Georgian decorative-applied objects; a photographic enlarger and projector sit with cutting devices; on the walls, theater designs, an etched portrait of his mother, a woman’s mask étude, King Lear illustrations, a “rehabilitation” sketch for an opera curtain, portraits of Savonarola and Dante; nearby, a restored video and a portrait of Kobuladze by Ketevan Magalashvili act like two steady eyes at history’s distance.

At the center is a shelf Kobuladze built—a piece of furniture treated like liturgy. It reads as iconostasis, but secular, partitioning the everyday from the transcendental while allowing passages between them. Its compartments—perfectly proportioned, tripartite, quietly obsessed with the golden ratio—hold a micro-cosmos: a reproduction of Fra Angelico’s Annunciation, glossy black Tbilisi ceramics, an image of J. S. Bach, “alchemical” minerals, micro-tools, a Dante relief, film negatives, scientific texts. The object performs as philosophy. It is both window and ledger, a device for seeing and a method for keeping accounts with time.

Comparisons to the James Ensor House-Museum in Ostend are apt: the unity of work, life, and milieu as a single organism. But the Kobuladze room is not a period reconstruction; it is a proposal for how to read an artist: not through masterpieces detached from context but through the ecology that made those works possible. It recasts biography as a spatial practice.

A shop that behaves like a footnote

The Foundation’s Art Concept Gallery—with its numbered objects, limited editions, and exhibition-specific merchandise—will be the most contentious element for some visitors. The anxiety is familiar: can the same institution that asks us to interrogate the political, conceptual, and historical predicates of art also offer us screen-printed T-shirts and sculptural bookends? There is no universal answer, but the local one is promising. The editions are not spun from generic design tropes; they emerge from collaboration with Georgian artists and designers, produced in small runs, and the proceeds are folded back into research and public programs. In this context—where funding infrastructures are fragile and where keeping an archive in the country is itself a cultural policy—the store reads less like a compromise and more like a mechanism. It’s the footnote that pays for the text.

There is also a subtler effect. By treating editions and books as part of the curatorial metabolism, the Foundation blurs a hierarchy that often hobbles institutions: “art” inside, “discourse” in the catalogue, “access” in the shop. Here, those vectors braid. You can exit with a tote and an argument, a poster and a genealogy.

What “transition” names now

If the word “transition” feels tired, it’s because it’s been used to describe everyone else’s future and no one’s present. This exhibition refuses that laziness. In its historical reconstructions, it shows that the early 1990s were not a waiting room but a laboratory in which Georgian artists engineered languages equal to their weather. In its contemporary framings—Parajanov’s backstage as historiography, Shengelia’s accident as epistemology, Danelian’s capriccio as ethics, Kobuladze’s shelf as theology of proportion—the program insists that transition is not a path from instability to stability. It is a habit of form. It is the way materials and minds behave when the ground is moving and likely to continue moving.

Institutionally, the Foundation wagers that a private model can underwrite public goods: research, conservation, the building of a new ecosystem that aligns heritage with infrastructure and curatorial innovation. That is not a modest claim. But the proof is on view, not in prospectus. Works long preserved abroad by a sympathetic collector are seen in Tbilisi; archives are staged with the dignity and risk of artworks; a generation of artists is discussed in terms other than provincial discovery or geopolitical tokenism.

The most persuasive moments are the least declarative. A pasted train ticket in Kacharava’s diary-painting. The startled face of Tsetskhladze’s tiger stepping past its own border. A blurred cheekbone in a Shengelia print that feels more like breath than skin. The ornamental logic of a Danelian background that refuses to be background. The golden-ratio insistence of Kobuladze’s shelf, which silently teaches proportion as ethics. Together they propose a way of seeing Georgia that is neither “after empire” nor “before Europe,” but decidedly here: a culture fluent in thresholds, committed to memory without nostalgia, and prepared to let its institutions behave like the art they host—experimental, dialogic, and built to move.

By Ivan Nechaev