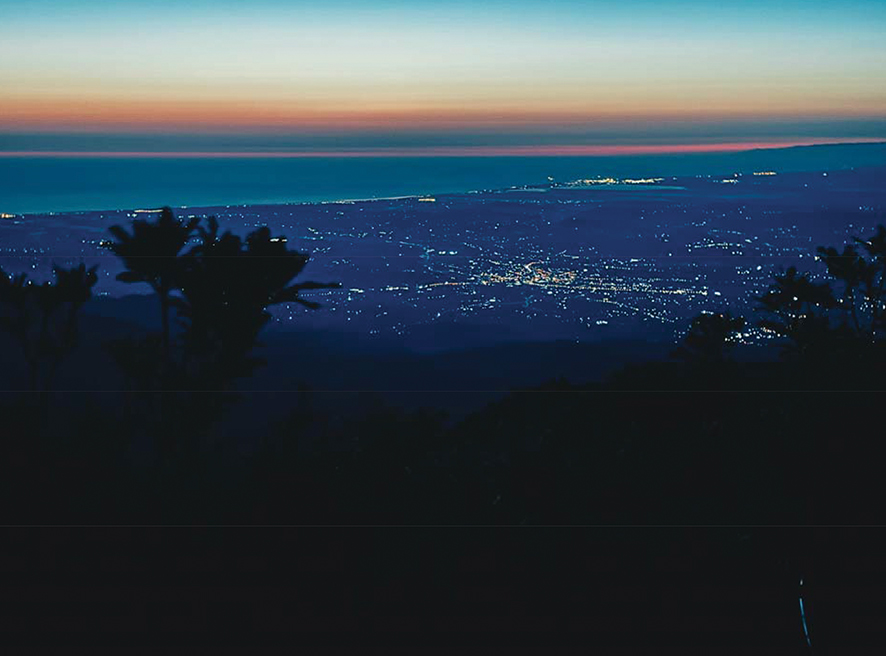

At 2,700 meters above sea level, on the mist-wreathed ridges of Gomis Mta in Guria, Georgia, the first edition of Gomi Mountain Fest took place this August. The organizers billed it as “two days above the clouds, in another reality,” and for once the marketing slogan was no exaggeration. Here, where even the standard tourist lookout feels dwarfed by the shifting sea of mist, Georgian electronic musicians gathered to create what could be called the country’s first attempt at ritualized raving in the sky.

The event’s program, running from the sunset grooves of Whino B2B Nikkol to the all-night trance of VFY (Vision From Yesterday), was less important than the fact of its location. A festival is always more than a schedule of DJs—it is an anthropology of space. To understand Gomi Mountain Fest is to place it within a global history of music and altitude: from the Incan ceremonies of Machu Picchu, where music and mountain were inseparable, to the notorious high-altitude psytrance gatherings in the Himalayas that became pilgrimage sites for European backpackers in the 1990s.

Mountains as Cultural Stages

Mountains have long been stages for encounters with the sacred. In Mircea Eliade’s theory of the axis mundi, high peaks connect the earthly and the divine. Georgians, too, have their ancestral memory of mountains as liminal spaces: sacred groves and highland sanctuaries dotted across Svaneti and Khevsureti served as sites of ritual feasts and collective gatherings. By transporting club culture into this terrain, Gomi Mountain Fest tapped into something older than rave—an echo of premodern cosmologies where altitude itself was an amplifier of experience.

Sociologist Victor Turner described ritual as “anti-structure”—moments when social hierarchies dissolve and participants enter into communitas, a sense of shared humanity. Raves have long been studied in precisely this Turnerian framework. What happens when the stage is not a warehouse in Berlin or a basement in Tbilisi, but a mountain crest where clouds swirl beneath dancers’ feet? The geography itself becomes part of the rite.

Georgian Electronic Underground Above the Fog

The lineup reflected the diversity of Georgia’s electronic underground. Whino, with his acid-drenched deep house, opened a journey that blurred nostalgia and futurism. JSHKY, a DJ/VJ hybrid and founder of MOMTABARE, built dynamic collages that moved from electro to Italo disco, embodying the hybrid eclecticism of post-2020 Georgian club culture.

At dawn, Ottonian B2B Neon Warrior injected historical consciousness into the mountain air: their Detroit- and Birmingham-inspired techno recalled electronic music’s origins as a form of resistance against industrial decline and racialized oppression. That lineage matters. To hear such references on Gomis Mta is to understand electronic music as a transnational language: Detroit’s ghosts now haunt Georgian clouds.

Later, Generali Minerali, with his machine-funk abstractions, and Skyra, whose recent vinyl release Birth After Deathsituates him at the emotional edge of Georgian techno, demonstrated how local producers are claiming space on the international circuit. Hamatsuki, a resident of Bassiani’s queer Horoom nights, carried the mood into dusk, proving that mountain festivals can be as politically charged as club basements. And when VFY, the trance alias of Erekle Tabukashvili, closed the festival, his experience anchored the night in decades of underground credibility.

The Phenomenon of “Above-ness”

There is a sociological fascination with verticality. Philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has written about how elevation alters perception, both literally and metaphorically. High places detach us from everyday structures, producing what anthropologist Tim Ingold might call a “dwelling perspective” in which the landscape itself reconfigures social relations. Dancing on Gomis Mta is not only an aesthetic choice but a phenomenological experiment: music becomes inseparable from altitude, from cold air and thin oxygen, from the shifting horizon of mist.

Festivals like Boom in Portugal or Ozora in Hungary have long cultivated rural escape as part of their identity. Yet Georgia’s Gomi Mountain Fest carries a different resonance. For a country whose electronic scene is internationally known for Bassiani’s subterranean spaces, a festival “above the clouds” symbolically rebalances the geography of Georgian club culture. It suggests that electronic music here is no longer confined to basements and urban margins; it has claimed the vertical axis, from underground to sky.

Tourism, Economy, and Memory

Anthropologists of tourism note how events can transform marginal regions into cultural destinations. Guria, often overlooked compared to Tbilisi or Adjara, now gains a symbolic claim in Georgia’s cultural map. The act of drawing hundreds of dancers up mountain trails turns geography into economy. In this sense, Gomi Mountain Fest follows a trajectory seen in Iceland’s Secret Solstice or Morocco’s Oasis Festival, where remote landscapes are recast as temporary capitals of global youth culture.

But there is also a risk. Festivals in fragile landscapes—from Burning Man in the Nevada desert to full-moon parties on Thai islands—often struggle with sustainability and overexposure. Gomi Mountain Fest, still intimate in its first edition, faces the paradox of success: how to grow without damaging the very atmosphere of “other reality” that altitude provides.

Potential and Points of Growth

As a first edition, Gomi Mountain Fest demonstrated immense potential. Georgia has the chance to cultivate a festival that could rival Europe’s rural icons like Boom or Ozora, but with its own mountain identity. Yet there are also crucial points of growth:

Accessibility and Inclusivity: Charging for entry and fencing off a mountaintop risks transforming a shared natural heritage into private territory. For locals, whose ancestral relationship to Gomis Mta is cultural as much as scenic, this could breed alienation. A more sustainable model might avoid ticketing and instead monetize through services: transport, camping rentals, food, and curated experiences. This would keep the summit open while still funding the event.

Sustainability: Fragile highland ecosystems suffer under heavy footfall. Burning Man in Nevada and Boom Festival in Portugal have faced criticism for their environmental impact. Gomi Mountain Fest must preempt this by investing in waste management, eco-friendly infrastructure, and community integration.

Integration with Local Culture: Guria is famous for polyphonic singing traditions, feasting rituals, and pastoral life. Future editions could experiment with dialogues between electronic music and local traditions—not as folklore tourism, but as genuine collaboration. Imagine a dawn set where a Gurian choir overlaps with ambient electronics, echoing across valleys.

Economic Model: The real revenue potential lies not in exclusivity, but in experience. Transfers from Tbilisi and Batumi, guided hikes, local gastronomy, art installations—these can form an economy without enclosing the landscape. This service-based approach mirrors Iceland’s Secret Solstice, which thrived on package experiences rather than ticketed exclusivity.

Curatorial Expansion Beyond the Pulse: The mountain begs for more than rhythmic intensity. While the nocturnal rave format is essential, the daytime atmosphere could host ambient, experimental sound art, and even contemporary academic music. Imagine an afternoon concert of drone and choral polyphony echoing through the valleys, or an installation blending field recordings of Gurian nature with electronic textures. This would attract new audiences—intellectual, artistic, international—without diluting the core rave identity.

The Liminal Future

The inaugural Gomi Mountain Fest may be remembered less for logistical perfection than for symbolic resonance. It expanded the coordinates of Georgian rave from basements to sky, reactivating ancient mountain symbolism in electronic form. In a country where Bassiani has already been a symbol of resistance, the festival points toward a new horizon: rave as communion with landscape.

The challenge now is to refine without flattening—to scale while preserving intimacy, to earn without enclosing, to grow while staying porous to local communities. If organizers succeed, Gomi Mountain Fest could become a defining ritual of Georgian summers: a gathering where music, geography, and society fuse above the clouds. A new ritual had been born on the spine of Guria—fragile, euphoric, and full of potential.

By Ivan Nechaev