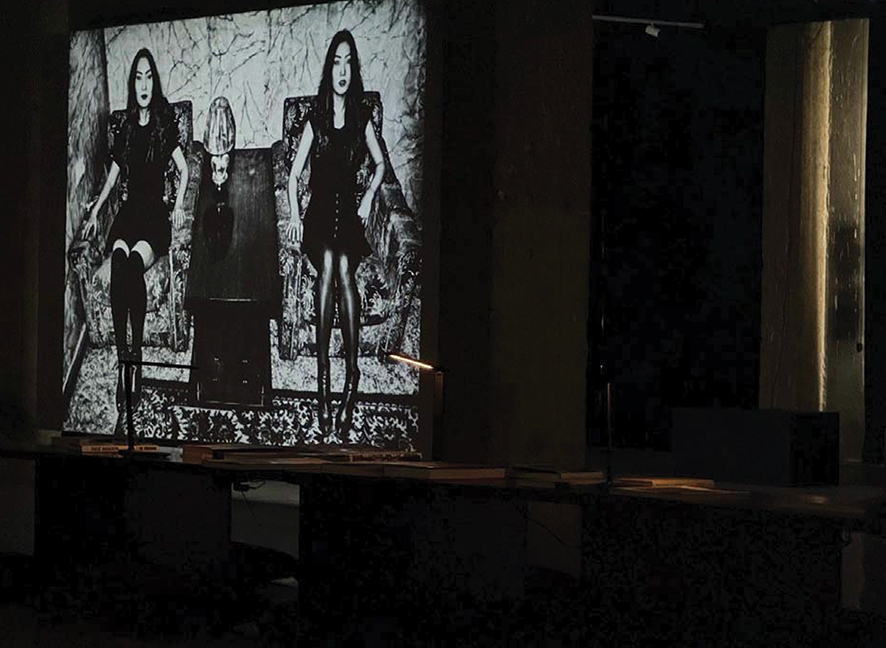

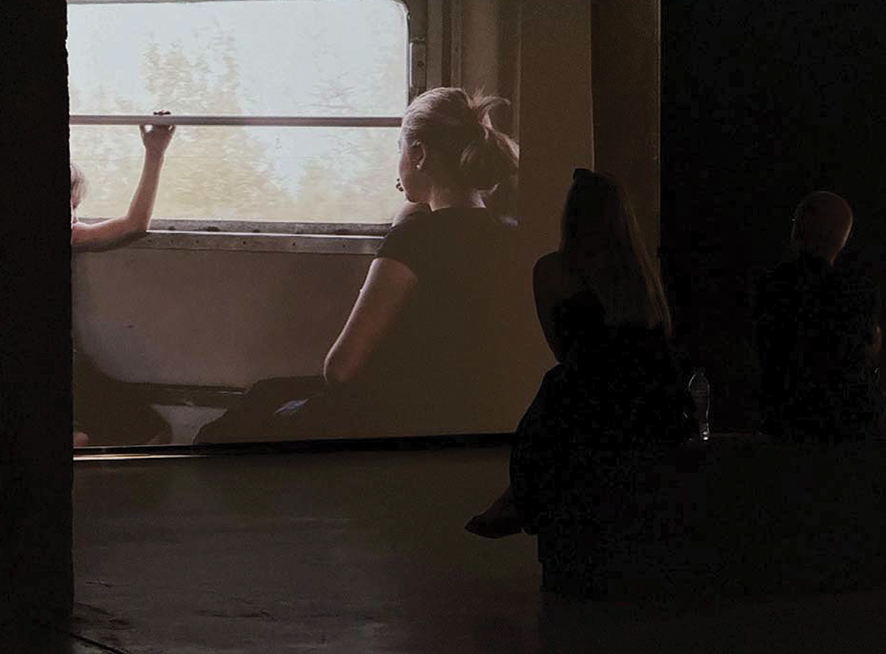

In the darkened hall of the Tbilisi Photography and Multimedia Museum, nine screens glimmer with images that breathe through silence. The space fills not with declarations, but with textures — of memory, rupture, displacement, and proximity. With Those Who Know Secret Things or Else Alone, the flagship exhibition of the 2025 Tbilisi Photo Festival, curated by Nestan Nijaradze in collaboration with Magnum Photos, reveals photography as a threshold — a membrane where the visible and the unspoken pass through each other. The exhibition forms no single story, but unfolds as a field of encounters, where every frame gathers the atmosphere of a world suspended between forces, bodies, and time.

Thomas Dworzak’s Kavkaz begins like a song of return. Georgia, the Caucasus, becomes a terrain where devotion, trauma, and belonging are fused. His images hold both the heat of wartime memory and the cool intimacy of everyday life. They emerge from within the social fabric — not as portraits of the other, but as gestures of fidelity. Dworzak raises a visual toast not to an idea, but to people and their textures, to the accident of having belonged somewhere with the depth of obsession.

In Niagara, Alec Soth turns his lens toward a landscape soaked in metaphor. The falls shimmer behind motel curtains, above pawnshop glass, inside letters that trace love and its evaporation. The project unfolds as a murmured ballad of disillusionment, with every frame thickened by absence. Soth composes with restraint, letting the emptiness of rooms and the soft decay of ritual speak to a broader sense of emotional gravity. His photographs linger at the edge of confession, where vulnerability loses its urgency and becomes form.

Black’s American Geography unspools across highways and hollows, forming a dense map of economic exclusion. His stark monochromes do not flatten time but concentrate it. Each image arrives with a quiet pressure — faces, fields, corners of forgotten towns. The United States appears less as a nation than as a network of statistical blind spots, connected through poverty zones that never touch center stage. Black writes in the language of evidence and accretion, assembling a geography that insists on being seen in its totality, one contour at a time.

Gregory Halpern returns to Buffalo in King, Queen, Knave and photographs its psychic atmosphere rather than its monuments. The city emerges as a series of symbolic fragments: gestures, shadows, collisions of light. His camera attends to the uncanny without theatrics, assembling a lyrical system where hope and entropy meet in the folds of ordinary places. The work reads like a slow, continuous dream — one in which meaning floats just below the surface of objects and people, always about to announce itself.

Jacob Aue Sobol’s With and Without You spans continents, relationships, and years, but it orbits around a single center of gravity: the act of intimacy. His black-and-white frames pulsate with warmth and fracture, drawn from encounters in Bangkok, Tokyo, Guatemala, Siberia, Copenhagen. The photographs breathe with the rhythm of someone who walks beside, who listens, who enters the moment without asking it to perform. Sobol’s practice is anchored in human connection, built through participation rather than distance, shaped by the repetition of emotion rather than narrative.

In Valparaíso, Sergio Larraín returns to the port city of his youth and lets it unfold like a remembered verse. The city, perched between ocean and Andes, slips through his lens as if composed of fog, angles, and memory. Larraín does not pursue spectacle but invites the everyday to reveal its own choreography — staircases, window frames, empty alleys. Each photograph appears to have been found rather than taken, as though it arrived from another dimension of time, still pulsing with the breath of its original moment.

Nikos Economopoulos gathers his images of the Balkans like fragments of an epic poem. Faces, ruins, gestures flicker through a region governed by feeling rather than resolution. His camera moves through spaces charged with emotional contradiction — celebrations that tremble with foreboding, silences that vibrate with unspoken tension. The work does not settle into narrative arcs; it gathers intensity through accumulation, assembling a region of pure symbolic saturation, where identity and danger live inside the same breath.

Ferdinando Scianna composes The Sicilians as an act of cultural attention, turning his lens not on a place but on its people as living scripture. His photographs carry the weight of custom and the force of simplicity, building a visual architecture of posture, gesture, and dignity. The work is infused with a rhythm that belongs to ritual and ancestry, not to the news cycle. Sicily is not captured. It reveals itself through the faces and ceremonies of those who carry its continuities forward, stone by stone.

Larry Towell enters the world of the Mennonites with a patience that allows time itself to change tempo. Mennonites is both document and diary, built from the trust between observer and observed. His photographs are filled with hushed moments — domestic scenes, ploughed fields, silent kitchens — drawn from a community that marks its difference not through resistance, but through devotion to continuity. Towell gathers these images as a liturgy of small details, as a way of witnessing lives shaped by humility, repetition, and spiritual precision.

Lua Ribeira constructs Subida al Cielo as a constellation of deeply theatrical encounters, each charged with the tension between representation and transformation. Her images borrow their symbolic weight from mythology, religious ritual, and vernacular gestures. Migrants, cognitively disabled women, processions of Semana Santa — each subject is staged not for clarity but for resonance. Ribeira creates a grammar of figures suspended in symbolic space, where identity dissolves into movement, and gesture replaces explanation.

Antoine d’Agata, in Method, turns the lens into a tool for confronting structures of power that shape contemporary violence. His images carry the texture of delirium, mapping a world in which brutality hides inside normalization. Bodies appear in fragments, faces blur, spaces collapse into heat and darkness. This is not a photojournalistic account, but a psycho-political meditation on extremity. D’Agata distills the forces that govern the present — surveillance, media, religious orthodoxy — into raw visual sensation, one that vibrates with moral exhaustion.

Sohrab Hura, in The Coast, follows the edge of the sea as if it were a psychological fault line. The images carry the volatility of sudden shifts, mirroring the emotional climate of a society frayed by tension. Faces contort, bodies shiver, weather presses against skin. The shoreline becomes a membrane that barely holds together a fragile sense of order. Hura allows chaos to surface gently, not as explosion but as accumulation, composing a suite of images that feel like aftershocks of an invisible quake.

Yael Martínez’s Luciérnagas begins in grief and ends in a visual rite of illumination. After the disappearance of family members in Guerrero, Martínez reimagines mourning as a symbolic process. His photographs are pierced and backlit, turning absence into architecture. These images radiate — not from the center, but from the wound. Fireflies become the carriers of memory, carriers of ritual, carriers of a luminous language that refuses to let violence erase what it cannot name.

Moises Saman composes Discordia from years of immersion in the Arab Spring. The sequence builds not from reportage but from a deep listening to atmosphere — repeated gestures, haunting fragments, gestures in flux. Through layered spreads and open-ended sequences, Saman portrays the emotional weather of revolution. Faces recur. Streets blur. History reconfigures itself without resolution. The book reads like an epic told through ellipses, through the silence between moments, through the untranslatable weight of surviving unrest.

Cristina de Middel, in Journey to the Center, constructs a migration narrative that traverses myth, danger, and political opacity. Her images, often staged and interwoven with found material, assemble a kaleidoscopic account of the journey through Mexico toward the U.S. border. She draws from magical realism not as style, but as structural possibility — where fiction and fact coexist in a shared geography of longing. The result is not a linear testimony but a visual epic, where the dignity of movement and the chaos of crossing coexist in a tapestry of cinematic suggestion.

Jérôme Sessini returns to Ukraine across the years, from Maidan to Donbass, gathering a long arc of geopolitical trauma and resistance. His images do not fix events. They render states of being. The war becomes a mood that saturates surfaces — buildings, hands, eyes, air. Sessini’s camera listens to exhaustion, records the textures of siege, frames the fragile gestures that persist when ideology collapses into rubble. His Ukraine is not abstract. It is inhabited, haunted, and unfolding in the space between memory and the next alarm.

This exhibition offers a terrain of attention. Each image carries the density of another’s life — the rhythms of their language, the scent of their fears, the gravity of their gestures. Here, the image becomes a position, a way of holding space for reality in its layered forms. The viewer walks not along a path of interpretation, but through a landscape of presences, held in light and silence. Photography, in this constellation, approaches the power of ritual: a way of staying close to the pain of others, and of recognizing the fragile architecture of being alongside.

By Ivan Nechaev