Some choreographers build monuments; George Balanchine built architecture that breathes. At the Evening of George Balanchine’s Choreography—presented by the State Ballet of Georgia at the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet State Theater—four of his seminal works were performed in succession, offering not a retrospective but a kinetic essay in neoclassicism. Carefully curated and staged by Balanchine Trust répétiteurs Bart Cook, Maria Calegari, and Ben Huys, the evening delivered a layered experience: a return not only of Balanchine’s ballets to his birthplace, but of the ideas that shaped ballet’s modern trajectory.

The Tbilisi dance company, under the direction of Nina Ananiashvili, approached these works with clarity, musical intelligence, and an almost reverent restraint. Conducted with alert sensitivity by Levan Jagaev, the orchestra supported the music—from Bach and Mozart to Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky—with a transparency that allowed Balanchine’s pure choreographic architecture to shine.

A Blue Prayer in Motion: Serenade

The evening opened with Serenade, set to Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings in C Major. Created in 1934 as Balanchine’s first ballet in America, it still feels like an act of invention. The famous opening tableau—rows of ballerinas in blue, palms raised toward an unseen force—acts less as exposition and more as invocation.

Nino Samadashvili, Mariam Lomjaria, and Elene Gaganidze brought a nuanced grace to the shifting feminine energies of the piece, while Filippo Montanari and David Ananeli grounded the work with a sculptural masculine presence. The piece’s power lies in its unpredictability: formations dissolve and reform, as if ballet’s classical vocabulary were being rediscovered in real time. Balanchine’s use of asymmetry, musical phrasing, and sudden stillness anticipates everything from postmodern minimalism to contemporary installation aesthetics.

Here, the Tbilisi dancers honored the work’s internal contradictions—its combination of serenity and unease, fluidity and form—with a precision that never hardened into rigidity. The result was less about storytelling and more about sculpting time with the body.

Between Memory and Echo: Mozartiana

Following the intermission, Mozartiana (1981), Balanchine’s late work to Tchaikovsky’s Suite No. 4, Mozartiana, reoriented the tone into something darker, more introspective. The ballet is neither a tribute to Mozart nor to Tchaikovsky, but rather an eerie dialogue between the two—a baroque echo chamber refracted through modernism.

Nino Khakhutashvili performed the central role with quiet intensity, supported by Joshua Ninamaker and Demian Reshetniak, whose solos lent sharp, musical articulation to the play of light and shadow. The choreography is filled with spectral flourishes: sudden arabesques that vanish like thoughts, precise turns that break just as the melody shifts.

What’s remarkable about Mozartiana is Balanchine’s refusal to romanticize Mozart. Instead, he refracts the composer through a 20th-century lens, much as Tchaikovsky did. The choreography leans into this ambiguity: canonical shapes are disrupted; musical phrases are answered with unexpected asymmetries. If Serenade was a love letter, Mozartiana is an intellectual conversation. The performance embraced this tension, never slipping into ornament, maintaining the cool integrity of Balanchine’s late style.

Duality in Dialogue: Concerto Barocco

The most overtly “musical” of the evening’s works was Concerto Barocco (1941), danced to Johann Sebastian Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, BWV 1043. Balanchine once said that this ballet is the music—and the dancers confirmed that axiom with a clean, virtuosic performance.

Sopho Tsintsadze and Salome Iarajuli embodied the dual violin parts with mirror-like clarity, never falling into mere mimicry. Their phrasing—sharp yet breathable—echoed the score’s complex interweaving. David Ananeli provided an anchoring presence in the male role, counterbalancing the continual modulation of the female leads. This ballet strips classical dance down to its essential grammar: lines, counterlines, breath, silence. The corps de ballet moved like an extension of the music’s inner logic, responding not only to rhythm but to harmonic texture. Every tendu, every pirouette, every port de bras became a sentence in Bach’s invisible libretto.

Here, Balanchine turns ballet into visual counterpoint, and the dancers rose to the challenge, delivering a crisp, unadorned performance that allowed the music’s geometry to radiate through the choreography.

The God Dances: Apollo

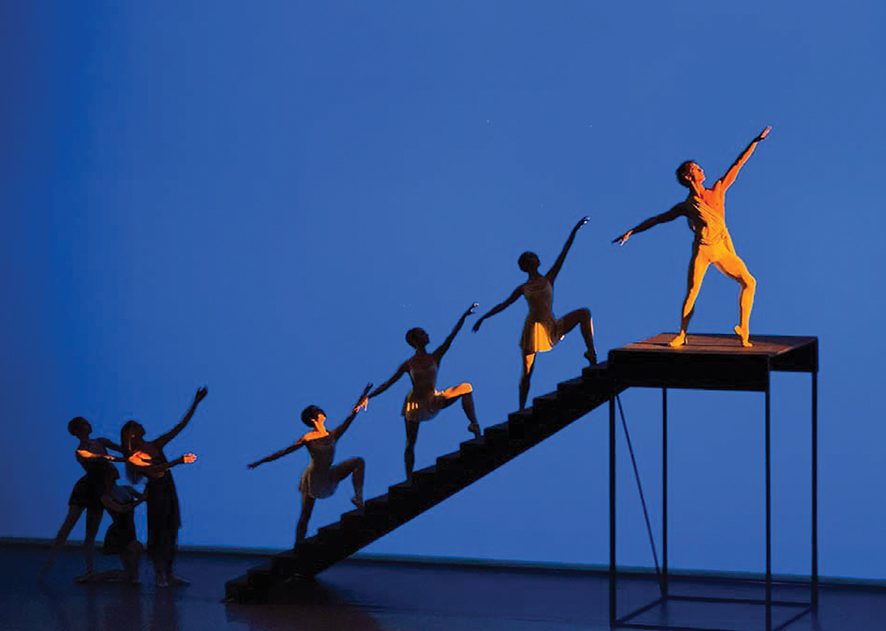

The final ballet, Apollo (1928), marked a symbolic return: Balanchine’s earliest surviving collaboration with Stravinsky and the first work where the contours of his mature style emerge with full force. Originally created for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Apollo has been continually revised by Balanchine, who gradually pared it down to its mythic core.

Efe Burak danced the title role with a controlled physicality, gradually evolving from raw kinetic energy into stylized grace. Laura Fernandez, Mari Elo, and Valerie Lin shaped the muses with cool, articulate sensuality—each muse a distinct voice in Apollo’s transformation.

Stravinsky’s score—severe yet luminous—was met with choreography that is stark, almost diagrammatic. Balanchine crafts movement that echoes both the austerity of Greek statuary and the linework of modernist design. The final tableau, in which Apollo leads the muses up a symbolic ascent, unfolded not as a narrative climax but as a distilled metaphor: art as transcendence through form.

The Choreographic Legacy Comes Home

Beyond the stage, the company has made a significant contribution to cultural memory with their 2021 documentary In the Homeland of Balanchine, available on YouTube. The film, featuring Artistic Director Nina Ananiashvili and Balanchine Trust répétiteur Ben Huys (a Prix de Lausanne laureate and former New York City Ballet principal), gives insight into the challenges of restaging Balanchine in Georgia during the Covid pandemic, including online rehearsals and cultural translation.

This tribute to George Balanchine is an act of intelligent embodiment. The State Ballet of Georgia is not attempting to “be” the New York City Ballet. It is discovering its own grammar within Balanchine’s language—melding Soviet ballet schooling, post-Soviet resilience, and global contemporary aesthetics. Balanchine’s ghost, if it hovered, did not demand reverence—it encouraged re-imagining.

In a world increasingly dominated by spectacle and superficiality, Balanchine’s ballets remind us that abstraction can be emotional, that structure can move us, and that modernity does not need to betray elegance. With this program, Nina Ananiashvili and the State Ballet of Georgia reminded their audience—and perhaps themselves—that ballet, when shaped by intelligence and heart, transcends nation and time.

By Ivan Nechaev