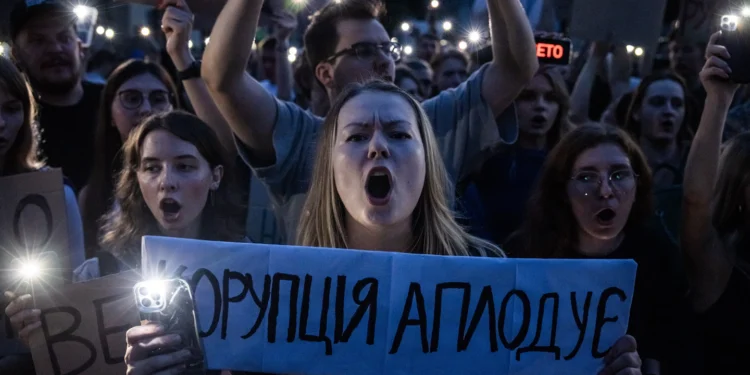

For the first time since Russia’s full-scale invasion began in 2022, widespread protests have erupted across Ukraine, this time not against foreign aggression—but against President Volodymyr Zelensky himself.

The protests, which have drawn thousands to the streets of Kyiv, Lviv, Dnipro, and Odesa, were sparked by the recent passage of a controversial law that places Ukraine’s key anti-corruption institutions under the authority of the Prosecutor General’s Office—an office directly appointed by the president. Critics argue the legislation undermines the hard-won independence of bodies like the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) and the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), long viewed as central to Ukraine’s democratic reforms and EU aspirations.

Since the outbreak of war in 2022, President Zelensky has enjoyed immense domestic and international support as a wartime leader. This week’s demonstrations, however, mark a shift—signaling public discontent with what many see as a dangerous consolidation of power under the guise of wartime necessity.

“This is not what we fought for in 2014,” said Olena Kovalenko, a protester in Kyiv. “We stood on Maidan for the rule of law. Now we’re being told it’s okay to dismantle judicial independence because of the war? That’s not acceptable.”

The law passed swiftly through parliament and was signed by Zelensky despite vocal opposition from civil society organizations, legal experts, and some members of his own Servant of the People party. International partners, including the European Union, also expressed concern, warning that the changes could jeopardize Ukraine’s path toward EU membership.

In a televised statement, President Zelensky defended the new legislation as necessary for streamlining investigations and protecting institutions from foreign infiltration—specifically Russian efforts to destabilize Ukraine’s justice system from within.

“We cannot afford paralysis in our institutions during wartime,” Zelensky said. “We are not dismantling anti-corruption. We are strengthening its capacity to respond swiftly and securely.”

But the president’s assurances have not quelled growing unrest. Anti-corruption watchdogs warn the reform effectively places independent investigations under political control, a move they describe as a return to the centralized practices of Ukraine’s pre-Maidan era.

The protests come amid mounting signs of war fatigue among the Ukrainian population, which has endured more than three years of brutal conflict, displacement, and economic hardship. With the battlefield largely at a stalemate and reconstruction efforts lagging, attention is increasingly shifting toward issues of governance, transparency, and the integrity of democratic institutions.

“The fact that people are willing to take to the streets in the middle of an ongoing war speaks volumes,” said Ilya Berkovych, a political analyst in Lviv. “It shows that democracy still matters deeply to Ukrainians, even in the face of existential threats.”

Some observers say the current protests could evolve into a broader political movement—especially if international donors or EU institutions begin to apply pressure or suspend financial aid in response to the legislative changes.

European leaders, including senior EU Commission officials, have issued cautious but firm statements urging Ukraine to maintain judicial independence as a condition for continued support and membership negotiations. The United States has yet to issue a formal statement, but several prominent think tanks and civil society groups in Washington have expressed alarm over the direction of Ukraine’s governance.

If not reversed or amended, the legislation could complicate Ukraine’s efforts to position itself as a credible candidate for EU membership—a key goal for the post-Maidan political generation and a strategic priority amid the ongoing war.

Header image: A woman holds a sign saying “Corruption Applauds” during a protest against a new law targeting Ukraine’s anti-corruption bodies, on a road leading to Ukraine’s presidential office, in Kyiv on Tuesday. (Ed Ram/For The Washington Post)