One of my first reports after moving to Georgia was from the Gori Stalin Museum. This was in 2010, when the country was ruled by President Mikheil Saakashvili, who was known as an anti-Soviet leader, the darling of the West. One of the laws adopted under Saakashvili was a ban on the use of any Soviet symbols.

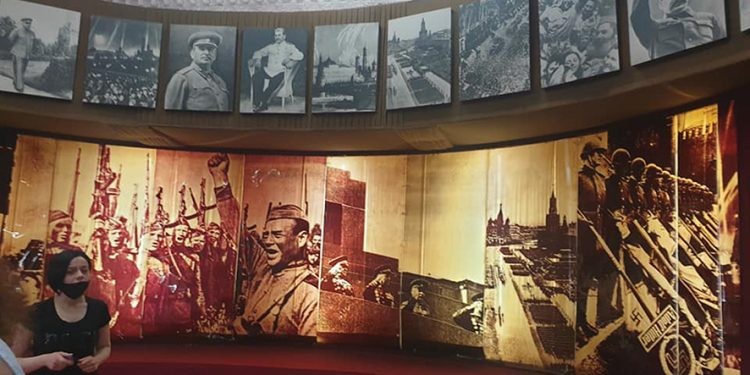

But, strangely, in this most progressive of all post-Soviet countries, in the Stalin Museum, I got the distinct feel of my Soviet childhood. In my hometown of Minsk, there is a similar place, called The Museum of the Great Patriotic War, which every school child had to visit. However, even there, the exposition was not as strongly tied to the cult of personality as in the museum in Stalin`s hometown.

The building of the Stalin Museum is a pompous neo-Renaissance palace, a central urban planning element, solemnly towering over all other buildings. Its construction began during the lifetime of the Soviet leader, and the museum was opened in 1957, four years after Stalin’s death. In the courtyard, there is a small house, in one of the rooms of which the son of a poor shoemaker and seamstress Joseph Dzhugashvili spent his childhood. To the side of the museum is the trailer-mounted armored railway carriage, in which the head of the Soviet state used to travel.

The building itself and its artifacts are remarkable, and even a little frightening. But most shocking was the style of the excursion offered in the museum. It was hard not to feel the strong Soviet presence, and, to me, it felt as if the collapse of the Soviet Union was someone’s absurd invention or, perhaps, a stupid dream.

Filled with a sense of pride in the great Soviet country and its leader, the guide spoke in detail about the milestones of the life and struggle of the “great father of the nations.” In the entire huge museum, with its pompous ceremonial staircases and huge halls packed with soviet artifacts, there is only one tiny room under the stairs dedicated to the fact of Stalin’s repressions, the atrocities of the NKVD, and with the history of the so-called Abkhaz War and the blitzkrieg in August 2008.

After that first visit to this strange museum, my reality split in two. On the one hand, I had come to live in a country whose changes for the better made even the most advanced Western powers gasp. The fight against corruption, reforms in the system of Internal Affairs, higher education, taxation, as well as the creation of exemplary Houses of Justice, where any document and any certificate can be issued in just half an hour – this was the business card of the new Georgia and its young president, who came to power in the course of the no less impressive peaceful Rose Revolution. On the other hand, this exemplary Western-style country had a Soviet past that was stuck in its throat like a huge undigested lump. And it still remains.

As I learned later, in the Saakashvili years, there were many different initiatives to change the exposition of the Stalin Museum. One of them was its transformation into the Museum of Soviet Propaganda, into something akin to the Holocaust Museum. All these attempts failed, though the Museum of Soviet Occupation was opened in a hall of the Simon Janashia Georgian National Museum in Tbilisi to tell of the above mentioned atrocities, 100 kilometers away from the veneration-loaded Stalin Museum in Gori. Who knows why the attempts to change the focus of that old museum failed. Perhaps its management (or even the country itself) did not see the need to change. After all, visitors by the bus load flock to this holy of holies of the city of Gori – the Stalin Museum is the most visited museum in Georgia!

A Second Visit in 2024

This year, I visited the city of Gori and the Stalin Museum once again. Zero changes were waiting for me! For the sake of objectivity, I will say that our wonderful guide Olga, a museum employee with 40 years’ experience, was ready to discuss with us several controversial issues of Soviet history and the biography of Joseph Stalin. However, as Olga told me at the very beginning of our conversation, she would not share her attitude towards the leader with me. She said everyone has his or her own attitude towards this person – and this was not our business.

Standing at the map of the Russian Empire, where all the places of arrests and exiles of Comrade Stalin are marked, it was funny to listen to fascinating stories about the wanderings of the future leader and his escape attempts.

“For his revolutionary activities, Stalin was arrested seven times,” the guide told us. “He was arrested in Batumi, then in Baku, and then St. Petersburg. He was exiled to Siberia several times. He managed to escape from all exiles except the last one, which was near the Arctic Circle. He tried to escape twice, but both times he was taken back, severely beaten, so that his left hand was damaged, which made it permanently shorter than his right hand.”

“Were all these arrests really connected to political activities?” I asked. “After all, there are rumors that Stalin, among other things, was engaged in bank robberies, in particular, on Yerevan Square in Tbilisi.”

“What are you talking about! There were no crimes! And no confirmation of this has been found!” Olga exclaimed, throwing her hands up. “He did not do such things. For money, there were other, ordinary party members. And Comrade Koba [Stalin’s pseudonym], was originally a member of the Politburo, a great thinker, author of many important articles!”

At this point, Olga told us about a secret printing house in Tbilisi, where, for several years, Comrade Koba and his colleagues printed leaflets in three languages.

“Is it true that Stalin nevertheless protected some of his fellow countrymen from the repressions?” I asked.

“Actually, many were protected,” Olga told me. “For example, the Soviet constructor Korolev, who was exiled to the island of Sakhalin, wrote a letter to Beria, and after that he was released. But for this, it was necessary to find a way to reach the right person. Millions of people were in exile, and neither Stalin nor Beria could know who was specifically there; they did not know the names or surnames of these people. And so, if the exiles had appealed to Stalin or Beria, and if they could not find evidence of crimes committed, maybe the prisoners would have been released.”

“How surprising! After all, Stalin was the ‘father’ of those great purges!” I exclaimed.

“Yes, this was allowed in the country, such was the method of struggle then,” Olga answered. “But they could not be responsible for each person specifically. The machine was launched, and those who fell under it became victims.”

The spacious halls of Stalin’s Valhalla are filled with visitors. For some reason, I could not help but notice the large groups of Indians and Chinese. They say that schoolchildren and students in Chinese schools still study Stalin’s biography in detail. So where else, if not in Gori, can one admire so many remarkable portraits of the “leader of the peoples,” and learn about his countless exploits, including those during the Great Patriotic War (which, in this museum, they still prefer not to call World War II), which, of course, was won by none other than “the great Soviet people under the leadership of Comrade Stalin.”

This time at the museum, I learned that “Comrade Stalin was a deeply religious man” who not only prayed and attended church himself, but also personally rehabilitated the Church during the war, which had suffered greatly after the October Revolution. I will leave this place without any comment. All of this could have been learned in recent years during church sermons, and via TV programs of state television channels like “TV Imedi”.

There are so many things happening in the world right now. And only this museum remains unchanged. Interestingly, its last update was in 1979. Preserved in their entirety are numerous, sometimes the most incredible, gifts given to Stalin from both citizens of the country and foreigners.

And to this day, at the entrance to a large hall decked out in red and black, you are seized by the feeling of immeasurable grief that was experienced by millions of Soviet citizens when they heard the news of Stalin’s death. In this mourning hall, the leader’s death mask is exhibited, as well as a large canvas with a painting of Stalin in his coffin, painted by a Georgian artist.

I took my youngest son on this latest excursion. It was his second visit to the museum. He doesn’t remember his first time: then he was a three-month-old baby. And now he is almost fourteen.

In order to draw a line under my son’s perception of this historical figure, I asked the guide to answer the question: “Was Stalin a positive or a negative political figure in general?”

This topic was clearly not to the guide’s liking, and she answered evasively: “I cannot tell you this for sure. Officially, probably, Stalin is a negative personality, if we take into account the policy of our state. But for different people Stalin may appear differently. I never talk to anyone about Stalin, I don’t even know what my friends, acquaintances, or neighbors think about him. We haven’t had conversations on this topic.”

Back home, I talked to my son, trying to gauge what he remembered from our museum tour. My son admitted that it seemed to him as if he had visited not only Stalin’s museum, but also the museum of Hitler. Have you ever heard of such a thing – a Hitler museum in Germany?! Such a museum is simply unthinkable, either in Germany or in Hitler’s homeland in Austria! But who knows what would have happened if Hitler had won that terrible war.

Another thing that impressed my son was the story about how Stalin refused to release his son Yakov from German captivity. The Germans offered to exchange Yakov for their Field Marshal Paulus. “I won’t exchange a soldier for a field marshal!” Stalin replied decisively. “That’s what kind of monster he was, truly made of steel: Sending his son to death without any hesitation at all!” my son remarked.

Who knows, maybe it’s this very persistence, these superhuman qualities, that still make some of Stalin’s fellow countrymen tremble in awe? A little boy from Gori, who the whole world feared, who opposed the West for many years, who planted many of his agents there, and who successfully dealt with his enemies abroad.

Thus, Comrade Koba finds himself again on a high pedestal – at least in modern Georgian (not to mention Russian) politics, as well as in the Orthodox Church.

“He received a country with a plow and left it with factories. He won the Great War, was an honest believer, a fair and modest person who wore the same uniform all his life!” these are the slogans of modern Orthodox conservative neo-Stalinists.

This is the story of the Soviet werewolf, who refuses to remain in the past, striving for the future with all his might.

By Tatjana Montik