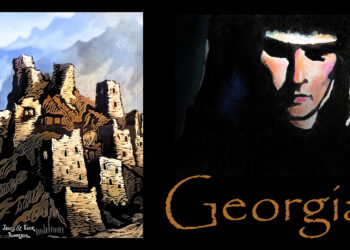

While many ruins of ancient kingdoms have either crumbled away from years of decay or been destroyed by war, some still remain very habitable to this day. The Georgian cave complex of Vardzia is one such case. With a monastery still in use and many of the caves still capable of providing adequate shelter, the complex has a special place in the Georgian national identity.

The approach to the complex takes visitors through a winding valley road along the Mtkvari River. The lush valley opens to a wide space of terraced fields and a modern village still inhabited by locals. A foot trail leads up to the complex where, at the first of these caves, the path continues under the dome of an old stone overlook still bearing ornate carvings around the entrances.

One of the first preserved rooms is a refectory, or dining facility, with seats and crud tables still lining the sides of the hall. These Spartan eating quarters consist of only a long stone bench and table where the monks would consume their simple rations of bread and wine. Some of the other cave compartments have visible signs of smoke, alluding to the use of camp fires in the complex.

However, as it would be improbable that anyone would light a fire in a closed compartment, it’s likely these markings were made later. When the Ottomans arrived in 1578, the area was a heavily trafficked road for trade and military travels. As a result, many merchants and traders would use the exposed caves as temporary lodging, thus the campfire residue.

Entering the The Church of the Dormition, we see the walls are covered in wonderfully preserved artwork. These paintings are breathtaking, and UNESCO states they are of “crucial significance in the development of the Medieval Georgian mural painting.” The interior is likewise amazing, with a barrel arch ceiling rising 30 feet (9.2 meters) above visitors. On the north wall are the famed paintings of Kings Giorgi III and Tamar the Great, both holding models of the church. Of particular note is an inscription that only Tamar has, saying, “God grant her a long life.”

Scenes of the life of Christ cover the remaining wall space, illuminated by only three large windows. To the rear of the church, through a tunnel, is a natural spring, where a virtually endless supply of potable water is available. This would have been invaluable during times of siege. A small tomb lies to the north, before a tight tunnel invites visitors to the next location.

The tunnel leads to another section of the complex, complete with additional housing, meeting halls, and cellars, before leading back down to the slopes of the complex. The wine storage cellars show an interesting view into life at the monastery, and many of the pits inside these special caves still have remains of Georgia’s famous Qvevri (clay wine amphora). These large handless amphorae would have stored vast liters of the church’s wine, shedding interesting light on monastic viticulture in the region.

For centuries, the site was home to some of Georgia’s earliest inhabitants. While much of the visible cave structures come from later medieval Georgia, the origins of the site go much farther back. Proof of pre-Christian habitation has been found at the site, indicating that the area was an important trading hub, and the long valley was likely an important highway for trade and military transport.

Evidence of the Tiralti cultures from around the 3rd and early 2nd millennium BC was found by archeologists in the mid-20th century, indicating the breadth of this ancient empire. Since then, it seems to have been an important center for trade, culture, and religion, particularly as Saint Nino brought Christianity in 327 AD. However, it was not until later that the greater cave complex would become the massive behemoth it is today.

The first phase of intensive construction began under the reign of Giorgi III, who ruled the Georgian kingdom from 1156 to 1184. The King, with his more aggressive stance towards Georgia’s enemies, saw in the beginning of what is commonly referred to as Georgia’s Golden Age. While the site was already a significantly populated area, the caves began to be carved out and a complex constructed in its early form under Giorgi III. As a result of this, he is forever memorialized in the Church that was built later. Following his death in 1184, his young daughter’s ascension to the throne would spell new additions for the Vardzia caves. Tamar the Great, also known as King Tamar, led the country from 1184 to 1213. Her reign is largely considered the most prosperous period of Georgian medieval history. During her tenure, the caves received their most iconic structure in 1186: The Church of the Dormition. It was at this time that some of the earliest paintings were created in the interior of this sacred structure.

Again, under the reign of King Tamar, the complex was improved. During her conflict with the Sultanate of Rum, or modern day central Turkey, the caves were used as a staging area for her armies. As they marched to victory against the Sultanate leader Suleiman II at the Battle of Basiani, the complex was again upgraded. These upgrades included advanced fortifications, additional habitation structures, and an integrated water and irrigation supply system that can still be seen today.

This upgrading would carry the cave monastery complex and accompanying village through generations of kings and queens. During their reigns, the caves saw continuous small improvements and additions, owing to its reliability and security. An earthquake in 1283 launched a massive reconstruction effort that deepened and reinforced the cave framework under King Demetre II. It is said that during the raids of the Mongol Horde in the late 13th century, many of the kingdom’s valuables were stored in the complex. However, in the late 16th century, the population of monks and assisting villagers departed the area, leaving the caves abandoned to time.

Today, the site is an impressive testament to Georgian strength and power, and a lasting monument to its history. The preservation of much of the artwork near the church is done through the Courtauld Institute of Art in conjunction with the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia and Tbilisi State Academy of Arts. It remains on the UNESCO World Heritage list and is a common location for tourists of all persuasions. Just as it has withstood invasions, monarchical collapse, and abandonment, it will likely survive the continuing test of time as one of Georgia’s most astonishing historical sites.

This article was made possible with the support and effort of the United Nations FAO and Elkana. Their financial and logistical resources bring awareness to the importance of Georgian ecotourism and sustainability of natural resources. Elkana and FAO are instrumental in helping people everywhere make their next destination in Georgia.

Blog by Michael Godwin