Civic engagement helps communities build resilience and enables citizens to participate in Georgia’s development. USAID and PH International’s Momavlis Taoba, or “Future Generation,” activity supports civic education and youth engagement in communities across Georgia.

Georgia is home to a vibrant civil society, although many communities lack adequate platforms for civic engagement. Greater youth participation is necessary to further strengthen community resilience and build a more inclusive society. Momavlis Taoba uses civic education, practical skills training, and small grants to enable young people to make a positive difference in underrepresented communities.

Through the program, USAID partners with the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport of Georgia, local schools, and civil society organizations to institutionalize civic education as a key component of Georgia’s public-school curriculum. Key activities include enhanced teacher training and civic curricula, practical civic education projects, and support for student-led civics clubs.

Civics clubs receive small grants enabling them to plan, manage, and implement their own community activities. These activities are designed to institutionalize civic education in Georgia’s school system, providing Georgian society with the capacity to ensure that young people have knowledge, skills, and opportunities to engage on important social issues. An impact assessment conducted by USAID in 2018 found that students at participating schools demonstrated significantly higher levels of voluntary civic engagement than those at non-participating schools.

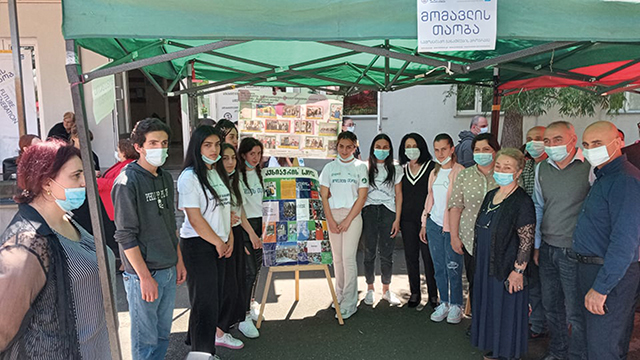

On June 10, GEORGIA TODAY was lucky to be invited to an exhibition of projects implemented by civics club school pupils in the Shida Kartli region.

The Kekhijvari State School hosted seven club presentations, though we were made aware that there were some 30 schools participating in 2020-2021. Overall, the project has worked with 60% of schools in Georgia in its 11 years, giving around three years to each school.

With 314 students attending the school, six of whom have special needs and three of whom are challenged with mobility issues, it seemed only natural for the Kekhijvari school to choose integration as its theme, aiming to raise awareness of and somehow normalize the participation of those with disabilities in a society which just a few years ago would see families hiding away disabled relatives in shame. To achieve their aim, grades 8-11 united with the special needs students to collaborate in arts and craft activities, in a final exhibition demonstrating to the wider community that people from every background and ability can create something beautiful. The classes also enabled carers to monitor and improve disadvantaged students’ fine motor skills.

Other schools chose even tougher issues, like Kvemo Gomi, which focused on gender-based violence by carrying out door-to-door surveys in their village to ascertain people’s perception of gender roles in Georgian society, then held a community meeting to discuss their findings and raise awareness. Other topics chosen were bullying and violence in schools, as well as broader community issues, like protecting the environment and climate change- things that are topical not just in Georgia, but worldwide.

The civics club of the state school in Daba Surami decided to clean up and spice up local parkland for use by their friends and neighbors. They did so by applying not only to the local government for funding, but also to company Energo-pro. With local volunteers, they were able to clean the area and rehabilitate wooden pallets into furniture, which the children painted in bright donated colors. Next, they are looking into encouraging both the local government and their community to make their good work sustainable with regular cleaning and care for the park.

“We ask schools submitting projects to contribute to their projects in resources, be it monetary or non-monetary, some percentage of the total budget, to show us what they can do,” says Marina Ushveridze from PH International. “Through training, they learn to look locally for supporters and soon come to realize that their projects often need less money than they initially thought to ask for: the local government gives something, a local farmer will donate something else, a parent will drive the students where they need to go. Simply put, the school civics clubs we work with learn to mobilize to find resources and then to bring those resources together. And this is really a positive tendency.”

Also present at the Kekhijvari exhibition was recently sworn-in Shida Kartli Governor Valerian Mchedlidze, who came to the post from a very useful background in donor-relations with the Agency of Protected Areas of Georgia.

“I was proud to see the projects these extremely active, motivated and well-trained students have implemented over the past year,” he told us. “The Shida Kartli region is very strong in the direction of education and sport. The biggest challenge we face is financing, and understanding and applying new technologies, new education tracks and new directions. As such, the work of ‘Momavlis Taoba’ is not yet sustainable. This region is very poor, but I have contacts and experience in attracting funds, so I hope to be able to work with future civics clubs here to improve our communities. These children are the future, and it is their job to change me and my generation [for the better]. I will work with them with pleasure.”

USAID funding for the Momavlis Taoba project is over as of June, but they are still committed to supporting civic education and will be announcing a new call for proposals soon. We asked Peter A. Wiebler, Mission Director of USAID/Georgia, how he felt seeing the students’ achievements.

“My reaction to these projects is always ‘wow’. It’s so inspiring. Georgia’s young people are really its biggest resource. In the broader education curriculum, there’s a lot of room not just for the staples of basic education and reformation- which the government has been putting a lot of emphasis on, and USAID has been supporting- but for a part about civics, about their role as citizens, their rights and responsibilities. That’s what I’ve seen throughout the years here: If you give them the tools, give them the support in their communities, help them make change, then Georgia’s young people are willing to take on those responsibilities.

“To me, there’s obvious progress being made and there’s a lot of hope for Georgia and its young people. We at USAID want to continue to work with the ministry and government to try to include and institutionalize the civics component into the curriculum, including in high schools. And we have willing partners in the ministry, all of them leaders who want to go in the same direction as us, as do Georgia’s youth. We’ll continue our support, and we’re going to build in more of a private sector angle: at the local level, there are companies and small businesses that want to see their communities grow, and the young people to stay in those communities and actually contribute, as opposed to going to Tbilisi for work, or leaving the country, which is a problem Georgia is facing. It’s not just about private sector money, it’s about private sector involvement and engagement: creating opportunities for young people, internships, getting young people exposed to how business works here. Overall, I feel very optimistic. I was nowhere close to where these kids are when I was their age, so I’m very impressed.”

“We’ve worked a lot on private sector engagement, and on our website initiatives.ge, we have a category [drop-down list] of donors, which demonstrates that school projects have been able to get funding from sources beyond USAID,” PH International’s Marina says. “This took some years to develop, but it happened. Schools come up with ideas, then we mediate between them and the companies. Schools need help formulating and presenting their project ideas concisely, and companies need help evaluating those ideas, having often not worked with schools before.

“Civic education has definitely become much more popular in schools among students, but also among parents,” she notes. “And school administrators are more supportive of this discipline because they have seen the benefits it brings to the school and community, and in the personal development of students.”

Naturally, support from school administrators is vital in further improving the quality of school-based civic education, as is their setting an example of how a true democracy works- with the students (as the constituents) knowing that their voices are heard and ideas and wishes taken into account.

“So much depends on the perception of the students themselves- if they feel that what they have to say has value, if they feel confidence,” Marina says. “Their involvement in civics projects demonstrates that they took the initiative to change things in their schools and communities. This affects students’ self-confidence, and develops in them skills of civic participation, skills of dialogue with decision-makers.

“Students come to see the school as a model of a mini-state, and if they are able to design the rules at school with their teachers and school administrators, they are more likely to respect those rules. Practicing democracy in such projects and then taking it into real life and finding solutions to real-life problems with the skills they develop in civics class, will ultimately positively contribute to the democratic culture in schools.”

During the exhibition on June 10, on behalf of PH International, Marina presented the Ministry of Education with the manual ‘Project Development and Management’ a step-by-step, 20+ page guide to civics project implementation. Based on the example of one illustrated project, it explains how to formulate a project idea, how to make school needs assessments, how to create a budget, whom to apply to, how to ask for funding, and so on. Each public school in Georgia also has a copy.

While Marina notes the goals PH International had for this timeframe have been achieved, she highlights that Georgian democracy is still fragile, and if support to civic education stops now, including external support from the donor community and other actors, the results achieved may end up slipping backward.

“Civics needs continued support from the donor and international community,” she says. “And also from other actors in the civics support ecosystem, which I see as the local business sector, local government bodies, and communities represented by parents.”

“The project being sustainable without the above-mentioned support, by which we mean the Ministry and schools running it, also depends much on the level of democracy in the country,” Marina tells us.

By Katie Ruth Davies