In today’s hyper-commodified landscape, words like “community,” “sharing,” and “solidarity” have been co-opted, becoming buzzwords in the lexicon of platform capitalism. Social media companies thrive on the idea of community while dismantling its very essence through commodification and monetization. This is the crisis to which An Atlas of Commoning: Places of Collective Production responds. The exhibition, hosted at the TBC Concept Flagship in collaboration with the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial, seeks to reclaim the language and practices of community, urging viewers to reconsider what “we” really means.

At its core, the exhibition critiques the loss of community ideals by focusing on commoning—the dynamic and often messy process of building and maintaining shared spaces and resources. This practice stands in direct opposition to the privatization and individualism rampant in contemporary urbanization. It is a call for the revival of collective governance and the rediscovery of public life, particularly relevant in a city like Tbilisi, where rapid urbanization has reshaped both physical and social landscapes.

From the Global to the Local: The Atlas as a Living Archive

One of the exhibition’s central features is its ever-evolving Atlas of Commoning. First conceived by ARCH+ and Carnegie Mellon University, the Atlas is an open archive of global grassroots projects that challenge the privatization of urban spaces. As the exhibition moves between cities, local case studies are added, keeping the Atlas in constant flux.

In Tbilisi, students from the Free University of Tbilisi, under the guidance of CMU faculty, contributed local research, ensuring that the Atlas reflects the city’s unique struggles and solutions. The result is not merely a collection of case studies, but a living, breathing document—a global commons of ideas and practices that grow with every iteration of the exhibition.

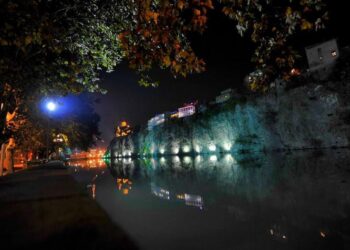

For Tbilisi, the Atlas connects with the city’s fraught history of urban development. The privatization boom that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union led to the erosion of public spaces and the rise of stark economic inequality. But the exhibition shows how local activists and community groups are now pushing back, reclaiming space and reinventing what it means to live together in the modern city.

Reimagining Production and Reproduction: New Forms of Spatial Organization

A particularly striking aspect of the exhibition is its focus on merging production and reproduction—terms that have long been segregated, both socially and spatially. Historically, labor has been relegated to economic production, while reproduction—childcare, household work, and caregiving—has been considered secondary. This separation has not only reinforced gender hierarchies, but also limited the potential for new, more inclusive forms of collective living.

The exhibition highlights initiatives that challenge these divisions. One such project, the Granby Workshop in Liverpool, illustrates how residents can reclaim control over their neighborhood’s future. Collaborating with the architecture collective Assemble, the Granby community transformed their urban environment by creating a social enterprise that produces ceramics from locally sourced waste. The workshop blurs the lines between production and reproduction, offering a model of communal life that benefits everyone involved.

For Georgian viewers, this theme of reclaiming public and private spaces holds particular resonance. The rapid urbanization that swept through Tbilisi after the 1990s has pushed many communal activities—traditionally integrated into public life—out of shared spaces. By presenting global and local case studies, An Atlas of Commoning invites visitors to imagine how similar efforts might work in their own neighborhoods.

Who Owns the City? The Battle Over Space, Ownership, and Access

At the heart of many of these commoning initiatives is a fundamental question: Who owns the city? As urban environments across the globe become commodified, with land and housing increasingly out of reach for the many, this question is more pressing than ever. An Atlas of Commoning directly engages with this issue, presenting examples of alternative ownership models that challenge the capitalist system’s grip on urban space.

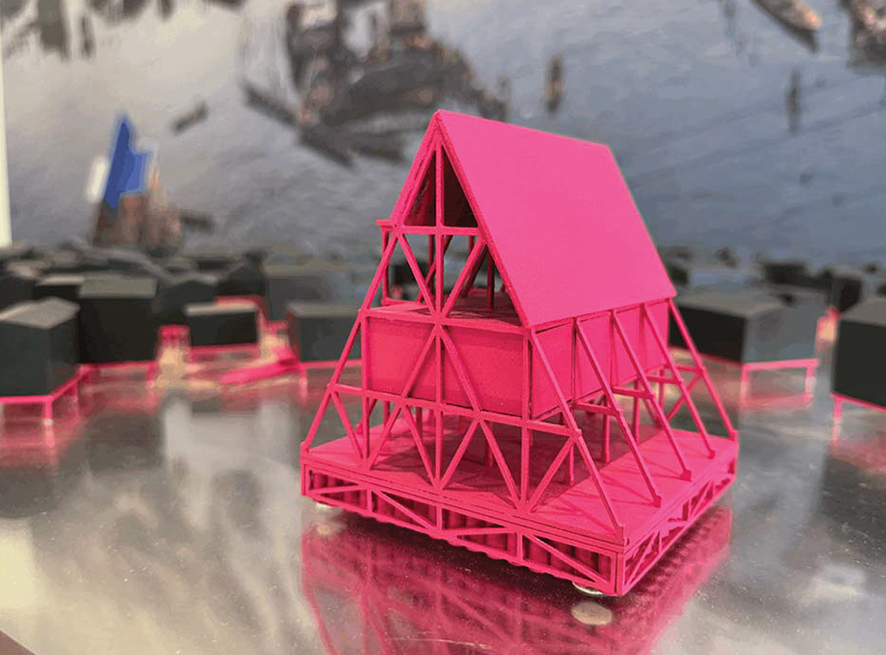

One especially playful exhibit, the Free Universal Construction Kit by Golan Levin and Shawn Sims, exemplifies this spirit of resistance. The kit consists of 3D-printed adaptors that allow different construction toys, such as Lego and Duplo, to be used together. By enabling the combination of these toys, which are normally segregated by proprietary systems, the kit symbolically questions the ownership of creativity and intellectual property.

In Tbilisi, the privatization of urban spaces and rapid gentrification have created fierce debates over who controls the city. The exhibition’s exploration of these issues has immediate relevance, urging citizens to think critically about how urban land can be shared and governed more equitably. As grassroots movements continue to emerge in Tbilisi—like those preserving the historical neighborhoods of Sololaki and Abanotubani—the lessons from this exhibition offer vital insight into alternative ways of organizing urban life.

Beyond Borders: Commoning as a Form of Global Solidarity

In its final section, An Atlas of Commoning turns its attention to the intersection of legal rights and global solidarity. It challenges the often-limited scope of human rights, which are grounded in national borders and state sovereignty. Commoning practices, by contrast, offer a form of governance and resource sharing that transcends legal frameworks, opening new paths for international cooperation and mutual aid.

A notable object in this section is Manuel Herz’s Rights on Carpet. The carpet is inscribed with declarations of human rights and invites visitors to engage with these texts in a visceral way—by sitting, kneeling, or lying down on them. It emphasizes the ongoing struggle to realize these rights in real life, rather than merely treating them as abstract legal principles. In Georgia, where minority rights and displacement are critical issues, the notion of solidarity beyond borders resonates deeply.

Commoning as a Revolutionary Practice: A Blueprint for the Future

What makes An Atlas of Commoning so powerful is its insistence on commoning as a process rather than a fixed state. The exhibition doesn’t present commoning as an idealized, utopian vision but as a messy, ongoing negotiation between individuals, communities, and systems of power. It is a practice rooted in the belief that collective governance, shared resources, and solidarity are the tools we need to create a more just and equitable world.

For Tbilisi, and for cities across the globe, this exhibition offers a blueprint for action. By focusing on the how of commoning—how resources are shared, how spaces are governed, how communities organize—the exhibition provides a roadmap for resisting the privatization and commodification that threaten urban life.

As cities face growing pressures from globalization, climate change, and social inequality, An Atlas of Commoning offers a timely reminder of the power of collective action. In reclaiming the spaces and resources that have been lost to commodification, we reclaim our right to live, work, and build together in ways that prioritize people over profit.

By Ivan Nechaev