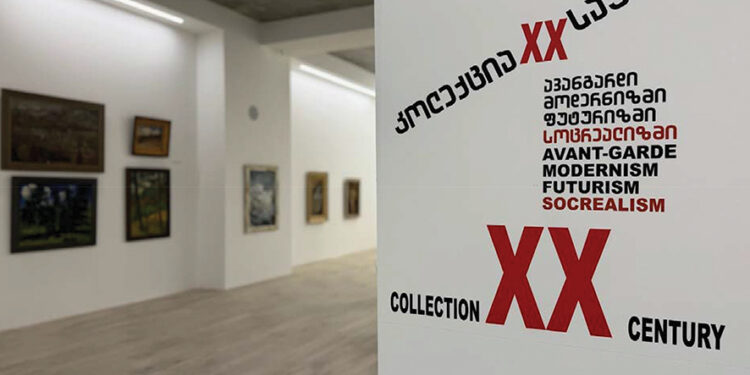

In a quiet, tree-shaded courtyard of Pavle Ingorokva Street 19a a cultural resurrection is underway. Behind the doors of Baia Gallery’s space for private collections, the exhibition ‘Collection—XX Century. Avant-garde and Modernism’ has cracked open a previously unseen archive of Georgia’s artistic DNA.

What we are witnessing here is less an exhibition than an aesthetic excavation. Baia Gallery, known for its deep engagement with Georgian visual culture, has gone subterranean—digging through the treasure vaults of private collectors to present works that have, in many cases, never before seen the light of public space. The result is a dazzling, sometimes dizzying constellation of masterworks that reframes the narrative of Georgian modernism and boldly reasserts the country’s position within the pan-European avant-garde.

The curatorial vision behind ‘Collection—XX Century’ does something radical: it proposes a new narrative of Georgian modernism, one that is not limited to institutionalized canons but instead builds a living, breathing mosaic of 20th-century innovation from private, often forgotten archives. It takes art history out of the ivory tower and into the salons of collectors, the corridors of émigré memory, and the silences of exile.

Here, David Kakabadze’s multiverse is finally laid out in full dimensionality. His photographic experiments from the 1920s—minimalist, searching, and eerily cinematic—converse with his Parisian works and the astonishing ‘Sketch of the Flag of the Republic of Georgia.’ This piece, part national emblem, part constructivist abstraction, is a missing link in our understanding of how political and visual ideologies once entwined.

Kakabadze’s ‘Abstraction’ anchors the show with scientific detachment and poetic tension, while his lesser-known photographic works underscore his interdisciplinarity—a trait many Georgian avant-gardists shared but were rarely celebrated for.

The familiar icon Lado Gudiashvili is present but cleverly defamiliarized. His works here, along with those of Shalva Kikodze and Sergo Kobuladze, are not merely nostalgic flourishes of Georgian exoticism. They’re read here as fragments of a broader surrealist and post-symbolist dialogue, closer to Giorgio de Chirico than provincial romanticism. Gudiashvili, seen in this constellation, looks less like a folklorist and more like a metaphysical alchemist of the Caucasus.

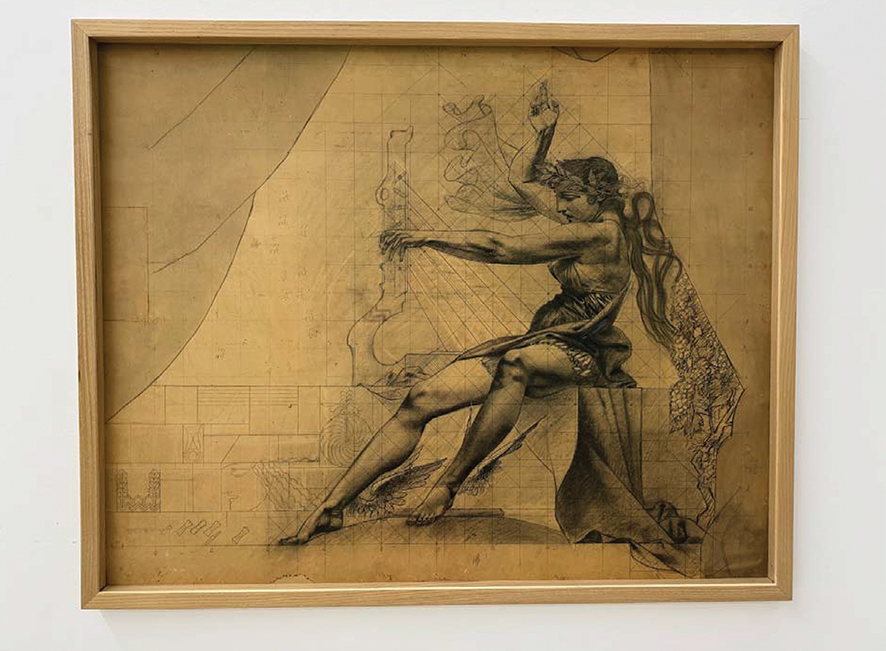

If Kakabadze is the theoretician of Constructivism, Petre Otskheli and Irakli Gamrekeli are its mythmakers. Their contributions to theatrical design, represented here with ‘Choreographic Costume’ and other sketches, remind us that Georgia’s modernism was not only visual but deeply theatrical, kinetic, performative. In their world, costume becomes abstraction, and the stage, a painting. Gamrekeli’s architectural severity and Otskheli’s expressive minimalism mark a moment when Georgian scenography was rewriting the visual language of Soviet-era performance.

And then there is Kirill Zdanevich, brother of the more radical Ilia, here presented with a pair of hauntingly intimate pieces: ‘Nude’ and ‘Still-life Against Mountains Background.’ They function like meditative pauses in an otherwise intense show, grounding the abstract and performative with a bodily, sensual quietness. Zdanevich is the one who reminds us that modernism is not always an explosion—it is sometimes the stillness before the quake.

A few steps later, Avto Varazi’s ‘Sleeping Woman’ and ‘Woman with Loose Hair’ offer a radically different but equally metaphysical vision. Painted in tones of melancholy and inward collapse, these pieces are haunted by war, ideology, and spiritual ambiguity. In them, Varazi paints not just bodies but epochs; disoriented, fragmented, and seeking repose.

Baia Gallery’s brilliance lies in assembling not just a canon, but a chorus. The inclusion of foreign artists who worked in Georgia, Vasily Shukhaev, Sergey Sudeikin, and Georgian émigrés like Vera Pagava and Felix Varlamishvili, blurs the tidy boundaries of “national art” in favor of a cosmopolitan vision.

Take Pagava’s ‘La Rencontre.’ Painted in France, yet steeped in a poetics that feels uncannily Georgian, it bridges her Parisian exile with a lingering homeland sensibility. Varlamishvili’s ‘Harvest’ and ‘View of Toledo’ similarly fuse Iberian landscapes with Caucasian chromatics, subtly articulating the identity crisis of the émigré painter.

Rounding out this panoptic vision are the “foreign” artists, though that term feels uneasy here. Sergey Sudeikin’s ‘Sadko. Underwater Kingdom’ is a fantasy fragment of Russian Symbolism that echoes with shared Georgian-Russian-Silver Age undertones. And Vasily Shukhaev’s ‘Bouquet of Peonies’ is an almost decadent contrast—lush, sensory, timeless.

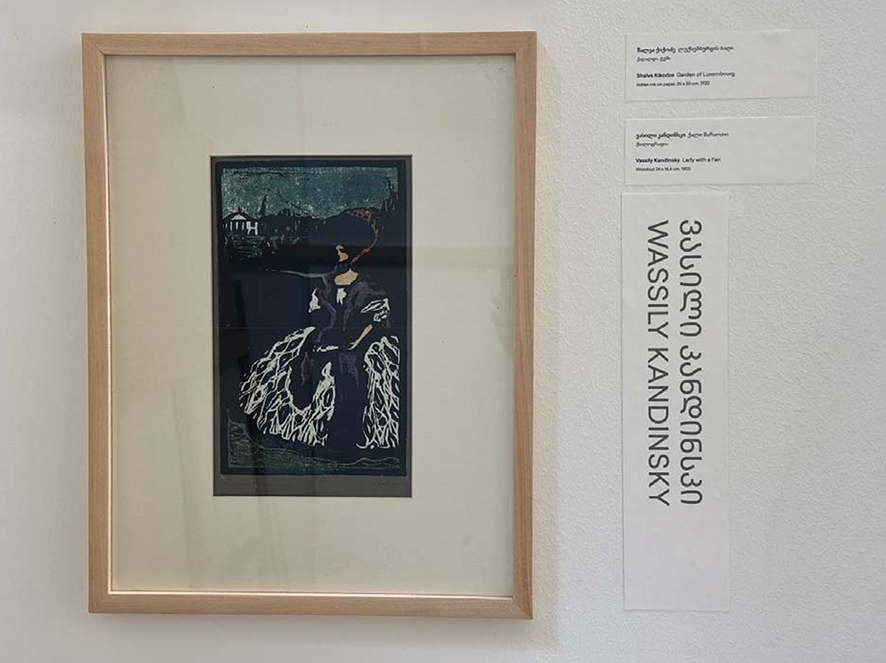

Nearby, a magnificent ‘Lady with a Fan’ by Wassily Kandinsky is not merely a showstopper but a conceptual axis around which the entire exhibition turns. Her bold ornamental structure and biomorphic curves echo through the works of the Georgian avant-garde—not as derivation, but as transnational resonance.

This exhibition argues, quietly but forcefully, that the Georgian 20th century was never provincial. It was plugged into a broader European and Russian avant-garde dialogue, from Suprematism to Cubo-Futurism, but always expressed in a language of its own.

The Exhibition as Counter-Canon: A Politics of Private Memory

This is an exhibition about art, but also about memory politics. Private collections in post-Soviet countries often fill in the gaps left by ruptured institutions, censorship, and cultural neglect. In Georgia, they have become not only personal investments but unofficial museums of resistance.

The show draws from the Baia Gallery’s own database of over 5,000 works, an archival project in progress that could one day redefine how Georgia writes its cultural history. In a country where artists have often been erased by political agendas or lost to diaspora, exhibitions like this one act as correctives.

What’s more, the exhibition allows us to see how generational echoes ripple through time. The flat, decorative lines of Shalva Kikodze reappear in the stylizations of Lado Gudiashvili; the philosophical somberness of Kandinsky finds an unlikely heir in Zdanevich’s sensual yet mystical ‘Still-Life Against Mountains Background.’

These are not just formal resemblances, but influences born of shared dislocations—of artists moving between cities, ideologies, and personal identities. ‘Collection—XX Century’ shows us that modernism in Georgia was never about isolation; it was about navigation.

In an era of rapid digital visibility and algorithmic canonization, ‘Collection—XX Century’ reminds us of something more intimate, and more profound: the quiet heroism of remembering. Of preserving. Of collecting not just art, but the fragile traces of modernity’s passage through a small but incandescent nation.

To visit this exhibition is to walk through a map of a hidden Georgia—not the one of postcard balconies and wine cellars, but the one of ideational ferment, aesthetic provocation, and historical disquiet. These works, long unseen, now return—not as relics, but as testimonies. And in their collective voice, we hear not only the art of the 20th century but the pulse of a nation still coming to terms with its modern self.

Collecting is never neutral. It’s a form of storytelling, a gesture of belief in the value of what might otherwise vanish. In this sense, Baia Gallery’s show is more than just an exhibition. It is an act of love—for art, for history, and for the radical beauty of rediscovery.

By Ivan Nechaev