The army in Georgia is a rightly celebrated and honorable organization that has stood in the defense of the oppressed. From combat on their own soil in 2008 to modern operations in Afghanistan and Central Africa, the Georgian Defense Forces (GDF) have conducted themselves well in the global security sector. Despite a miniscule size compared to other American or European partner militaries, its approximately 37,000 members carry a much heavier burden than many of their other counterparts.

With Azeri and Armenian forces consistently at each other’s throats and Russian forces routinely violating national sovereignty, the GDF is arguably the only force in the South Caucasus for peace, stability, and goodwill. This responsibility does not come without its requirements to be the most advanced and lethal military, capable of removing threats in a timely manner. For these reasons, the GDF must look at its future lethality and invest in its advancement.

The history of the martial skill of the Georgian or Kartli people is filled with exceptional stories of heroism, valor, and courage. Examples include the early Greek-influenced Cochian warriors, the knights of the Bagrationi dynasty, the famous 300 Aragveli, the battalions of Georgians in the Soviet Army fighting Nazi Germany, and the soldiers struggling to preserve the nation in the 1990s. The Georgian military spirit has, and still is, something to largely admire.

However, there still remains several proverbial chains holding the GDF back from becoming the regional power they must become. Conscription and the side effects surrounding it, the brigade and organizational systems, and the battlefield technology systems implemented are the three main points of concern. An examination and correction of these matters by the GDF stands to make the overall warfighting force the primary Eastern European based NATO force for good.

The institution of conscription and its place in the national defense framework is a solid weakness. This practice has been in place since 2017, after it was suspended by then Defense Minister Tinatin Khidasheli in 2016. While it had been said to be a far more reformed and enhanced version of the old system, multiple sources have described its training regimen as rudimentary and incomplete in terms or military relevance.

Indeed, many of those that serve in the conscript corps do little actual military combat exercises those that have served in professional Western armies would recognize. Serving primarily as an unarmed security service at government buildings and installations, these young men are a federally organized version of private security guards; the proverbial “mall cop.” While many of them do their level best in their required line of work, their use as a combat-ready and operationally competent force for national defense is plainly nonsensical.

The removal of this program could draw some ire from those with a traditional view of military service. In many Eastern and former Soviet bloc regions, this practice is almost a part of the national culture. Barring university entry approval, professional athletic obligations, or other medical exceptions, every young boy leaves his childhood home to become a “man” through the rigors of military service in defense of his hearth and home. However, this aged view of service has been far surpassed by the post-modern nature of warfare.

It’s no question that the warfighter of tomorrow will be a far cry from that of yesteryear, and in fact even that of today. Many of the West’s military recruitment models focus on not solely physical prowess, but also academic and educational aptitude. The need for junior soldiers to operate inside conflict zones using advanced technology, a high sense of cultural awareness, and an exceptional ability to adapt to new tools and techniques requires a far more extensive training and indoctrination regimen.

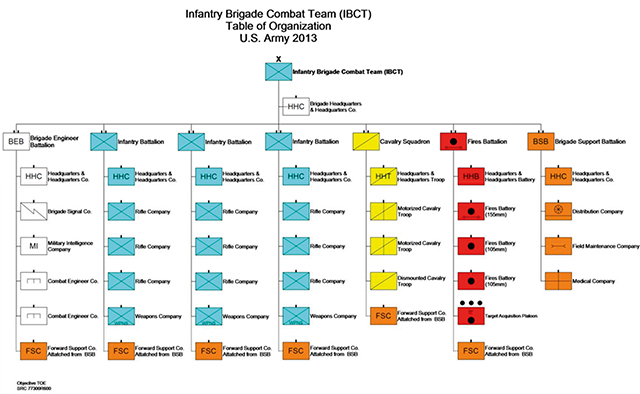

How these professional soldiers of tomorrow are organized significantly impacts the total warfighting efficacy of the larger units they are a part of. Allowing tactical and strategic command the tools of modularity with their units gives them an almost sliding scale of force response when deploying. Not dissimilar to the United States Army’s Brigade Combat Team (BCT) model, many Western militaries are shifting to this flexible, easily deployable, and self-sustaining template of force organization.

Currently, the GDF’s ground component, the Georgian Land Forces or GLF, maintains an outdated model of maneuver unit organization. Infantry brigades contain three infantry battalions, Artillery has its own artillery batteries, and so on, as each maneuver unit is homogeneous to its own branch type. Specialized units such as military police, special operations, combat engineers, and medical support units are organized separately. This type of organization is largely seen as ineffective to the advanced organization of tomorrow’s war.

By arranging the composition of the GLF units into something more effective, each maneuver unit gains a far greater ability to coordinate with supporting elements. This organization is often characterized by the United States Marine Corps’ Regimental Combat Team (RCT) or the aforementioned BCT configuration. By combining the infantry, artillery, armored, combat support, and combat service support elements into one maneuver unit capable of standing largely on its own, it becomes exceptionally more fluid.

In this model, each BCT/RCT arranges its composition of units around one of the three primary formats: light, medium, and heavy.

A light BCT/RCT places its focus on light infantry using smaller vehicles such as the iconic American-made “Humvee” or the Georgian Didgori-II, reconnaissance or commando elements, and man-portable indirect fire units able to maneuver in terrain that would be ill advised for heavy armored vehicles. Sometimes referred to as an Infantry BCT (IBCT), these BCTs are ideal for deployment in remote areas where logistics and movement considerations restrict the application of large equipment. In addition, they are useful in counterinsurgency or peacekeeping operations due to their low military and political footprint.

Heavy BCT/RCTs are more armor centric, with an emphasis on the Georgian T-72 variants of the Main Battle Tank (MBT), self-propelled artillery, and mechanized anti-armor assets. The focus is on near-peer enemy combatants with like armament, or alternatively in assistance of a lighter infantry-based assault of an urban key terrain feature. While these BCT/RCTs are resource heavy, they are essential to the diversity of post-modern battlefield conditions.

The medium BCT/RCT naturally splits the difference by providing a combination of highly mobile infantry by way of Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFVs) such as the new Georgian “Lazika” IFV, anti-armor support, and relevant indirect fire units including IFV-mounted mortar systems. As a flexible BCT/RCT, these allow commanders to deploy forces that are adaptable to a fluid and rapidly changing socio-political and military environment. This is particularly useful when C4ISR (Command, Control, Communications,

Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) may be limited or even not yet existent, and a form of ad hoc expedition force is required.

Each BCT/RCT, regardless of the format to which they center upon, have their own support units included in the BCT/RCT. This allows the necessary medical, communications, engineering, and other support units to become far more effective in their operations with their sister units within the BCT/RCT. In addition, when deploying abroad, particularly on NATO or UN missions, BCT/RCTs are able to organize rapidly and operate in a much more cohesive manner.

This combination of soldiers that are trained and prepared for tomorrow and a reorganized maneuver unit structure makes a force that is conducive to the needs of the next battlefield. The introduction of next-generation battlefield technology is the next step in maximizing the warfighting aptitude of the GDF.

The implementation of C4ISR advanced platforms at all leadership levels within the BCT/RCT facilitates a truly healthy command and control environment. This must be seamlessly available at all leadership positions, from rifle squads and gun crews to battalion and BCT/RCT command staff.

However, this network of C4ISR also goes beyond the BCT/RCT. This connectivity capability makes multi-domain interoperability through a unified network a reality, even linking extra-brigade units such as air support assets, electronic and information warfare elements, and other BCT/RCTs able to share relevant data. Additionally, making this unified network global in all of the GDF and relevant national security elements allows forces to consolidate, deploy, unpack and reconnect to this network with unrestricted and secure access.

Ensuring the security and operability of such a network, while it would be a potentially decade-long process, puts Georgia on the cutting edge of region and even global security initiatives. The interoperability between the tactical, strategic, theater, and even global or NATO-wide command levels is the true future of C4ISR.

For Georgia, with such a storied past of military excellence, these revolutions are instrumental in preparing the GDF for the next conflict. Georgia, while a small regional power, has the full capability to be a leading edge for NATO and the free world. It is true that these three aforementioned initiatives are not alone in the list of improvements for the GDF. However, they are among the core strategies that effect change at all other levels.

GDF lethality begins decades before the first shot is fired. With an eye to the future of post-modern security and stability operations, it is imperative that the relevant actions are taken now. These measures are aimed at ensuring that when that first shot is taken, it is on time and on target, with the complete military tactical, organizational, and network infrastructure behind it.

By Michael Godwin