This month, Georgian political leader Irakli Kobakhidze started a referendum to determine if people would be in favor of a military campaign against Russia. “Let the people say whether they want to open a second front in Georgia against Russia,” he annunced. The move, as he later stated, was just a stunt to frame his opponents.

However, the move galvanized a portion of the populace, as well as the West. In a poll conducted by the author on social media with over 600 participants, more than two thirds wished to see Georgia take up arms against Russia, underlining Georgia’s long-standing ambitions to reclaim its territory, taken from them by the Kremlin’s force of arms.

This seizure is unlikely to come without additional cost. Some Georgians have the notion that should those living in the occupied territories want to exclude themselves from Tbilisi’s affairs, so be it. If they wish to exempt themselves from being Georgian, they say, then there is no love lost through the decades of mistrust and conflict. Despite this, the potential for conflict remains.

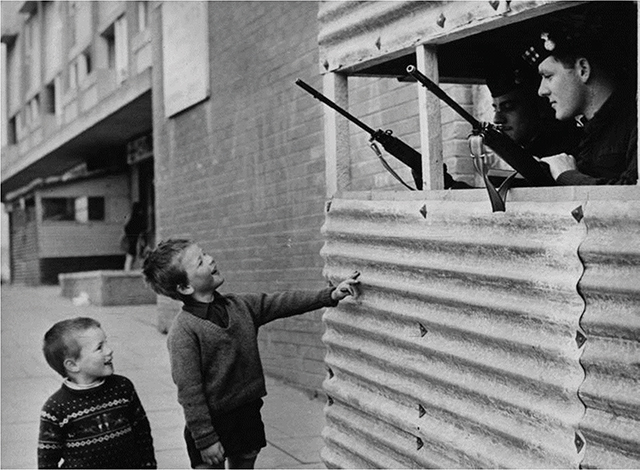

The prospect of reclaiming the territory in Tskhinvali comes with issues mirroring The Troubles in Northern Ireland

Last week, rumors circulated on social media that Georgian army units were moving towards Tskhinvali. While these were quickly put down to false information, it highlights an issue that Georgia will likely have to reckon with should they attempt to reunite with their territorial brethren.

This reunification is not unprecedented. One of Georgia’s closest allies has a similar experience. The UK spent decades fighting, thousands of lives, and millions of pounds working to bring their Irish neighbors into the fold. The United Kingdom’s history during The Troubles are recognized to have spanned from the 1960s and into the late 1990s; however, the roots go much deeper.

Tension between the Irish and the English is as old as the two nations themselves. More modern sources cite conflict as far back as the 17th century. The Ossetians in Georgian territory have similarly had differences with other Georgians dating as far back as the unification of the Georgian state in the 18th century. In the 20th century, the two came to blows, seeing troops sent in to establish governmental control.

After the 2008 war, South Ossetia has attempted to gain some semblance of legitimacy. However, only Russia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria recognize it as a nation – hardly a credible friends list. They have also struggled with infrastructure, development, and internal security, as Moscow has largely turned its back on the small mountainous pseudo-republic.

While the people in the occupied territories will eventually come out from the shadow of the Kremlin, it may be a better decision to let this occur naturally

The prospect of reclaiming this territory comes with issues mirroring The Troubles in Northern Ireland. Resistance, assimilation, and long-term insurgency all combine to give Georgia more than what it may bargain for. Tbilisi, for all its well-meaning and the fact that life in Tskhinvali would almost certainly receive an upgrade for reuniting with their former brethren, may want to pass on such a reunion.

Bringing South Ossetia back into the fold would most likely result in a long and drawn out simmering conflict, something the nation can surely do without. The breakaway region, long occupied and steeped in the false narrative pushed by the Kremlin, is convinced Tbilisi is set on destroying their cultural identity.

Any attempt to change the public perception of our neighbors in the northern mountains would be a long journey of assimilation and fighting disinformation. This warped view has become so ingrained in the latest generation of young Ossetians that it could be decades before they change their beliefs. This, combined with social strife and potential armed resistance, sets the stage for igniting the entire region in another war.

While the people in the occupied territories will eventually come out from the shadow of the Kremlin, it may be a better decision to let this occur naturally. To attempt to rip the proverbial bandage off could stir more problems than it solves. At the same time, it is Georgia’s responsibility to let them see the light of democracy and Western values, and lead them home on their own accord.

By Michael Godwin