A ghost lingers in the air at the Tbilisi Photography & Multimedia Museum (TPMM). It is not the kind that fades into the shadows—it is one that speaks, one that demands to be seen. The group exhibition Something Very Dear, curated by Ana Gabelaia and presented by the Tbilisi Photo Festival, the Tbilisi Photography & Multimedia Museum, and the Prince Claus Fund, is not a collection of images. It is an act of defiance. A call to remember. A refusal to be silent.

The works of nine women artists from across the world—Turkey, the Middle East, South Asia, North and South Africa—converge in this space, each bearing witness to an environment that is often unjust, violent, and cruel. But rather than focusing on the brutality itself, the exhibition turns our attention to what makes the struggle worthwhile. What is so dear that it must be defended at all costs? What remains sacred in a world that seeks to erase?

In an era of manufactured forgetting, Something Very Dear is a counter-attack. It resists the forced amnesia of war, displacement, and repression. Here, photography, video, and sound do not just document reality; they reshape it. The artists refuse to be passive chroniclers of suffering. Instead, they reclaim their own narratives, rewriting the histories that have been stolen from them.

The Fig Tree That Remembered: Larissa Araz and the Unfinished Story of War

What happens when history takes root in the body? ‘Begin to See through the Darkness’ by Larissa Araz emerges from a haunting image: a fig tree growing from the belly of Ahmet Cemal, a Turkish Cypriot killed in 1974 during the war in Cyprus. The fig—his last meal before death—takes root in a cave, transforming his body into both a tomb and a living archive.

Araz’s installation unfolds like a forensic investigation, traveling to Limassol in search of this fig tree, which exists in defiance of both nature and history. A cave, accessible only by sea, becomes a repository of missing bodies, a site where soil and identity blur. A coffin-sized photograph of the tree becomes a confrontation with erasure.

This is not merely an exploration of war’s aftermath; it is a meditation on the persistence of memory in the landscape itself. The fig tree, growing through the cracks of destruction, refuses to forget. And in its shadow, we are forced to reckon with the ghosts of conflict, still unburied, still waiting to be acknowledged.

Where Is Home When Home Is History?

What does it mean to belong when home is a story passed down through generations rather than a physical space? In ‘Where is home?’ Tahia Farhin Haque traces the aftershocks of the 1947 Partition through the fractured journeys of six sisters scattered across the globe. It is a photographic odyssey shaped by exile, reunion, and the cruel arithmetic of history—six left, one buried.

The series moves between time and geography, between the past and a present where racism and displacement remain constant. The American dream is shattered in Haque’s first week in the U.S. when a South Asian student is killed by the police, a system that coldly assesses her as having “limited value.” Here, exile is not just about being physically uprooted; it is about existing in spaces that refuse to see you as fully human.

By weaving her own family’s history into broader narratives of forced migration, Haque questions the very nature of identity. Can home ever be reclaimed, or is it just a mirage—a memory that dissolves the closer one gets? The photographs, rich with absence, force us to confront a reality that is both deeply personal and disturbingly universal: for many, home is not a place to return to, but a wound that never heals.

The Distance Between Hand and Mouth: Shayma Hamad’s Rituals of Grief

Some acts are so primal that they become invisible. Digging and kneading—two gestures that define the human relationship with land and sustenance—are reimagined in Shayma Hamad’s ‘The Distance of Death from My Hands to My Mouth.’ In Palestinian culture, these acts hold deep significance: digging is an act of resistance, kneading a ritual of remembrance.

But what happens when these simple gestures are criminalized? Under Israeli military orders, digging is restricted, and land becomes a site of contested ownership. Meanwhile, kneading, often performed in moments of collective mourning, transforms bread into an offering for the dead.

Hamad’s photographic installation documents a performance in which these acts unfold as quiet, repetitive defiance. Digging is not just about burial; it is about reclaiming a severed connection to the earth. Kneading is not just about nourishment; it is about preserving a culture that is constantly under threat. In the endless cycle of these movements, the past and present collapse into each other, forming a resistance that is both bodily and spiritual.

Cutting through Exile

Exile is often spoken of in grand terms—displacement, migration, the loss of home. But in ‘Therefore, I Cut,’ Sarah Kontar captures it in the smallest of rituals: the act of cutting hair. In exile, the salon becomes a living room, and the hands of friends become the only trusted ones.

Kontar documents a community of women who have lost everything except each other. Their conversations—whispered memories of war, survival, and love—are as much a form of resistance as any protest. By focusing on haircuts, an act of care rather than destruction, ‘Therefore, I Cut’ redefines the narrative of exile. It is not just about what is lost, but also about what is rebuilt in its place.

Through these simple, intimate gestures, Kontar reminds us that home is not always a place. Sometimes, it is a pair of hands, a shared memory, a small act of tenderness in an otherwise brutal world.

Listening to Water’s Silence: Dumama and the Ocean’s Archive of Violence

Can water remember? And if it does, who listens? Dumama’s ‘To Be a Voice / To Have a Voice’ is an installation of deep listening—a sonic excavation of the ocean’s hidden memories. The Atlantic and Indian Oceans, vast and indifferent, hold the echoes of forced migrations, hydrocolonialism, and the severed spiritual connections of Black South Africans.

Under apartheid, water-based spiritual practices were systematically erased, turning the ocean from a site of cleansing into one of alienation. But what if the water itself never forgot? Dumama crafts soundscapes that reconstruct the ocean’s memory of Saartjie Baartman’s journey—a woman reduced to spectacle, transported across waters as a human artifact. Through submerged frequencies and ghostly echoes, her story is retold in sonic form, resisting the silence imposed by history.

To listen to Dumama’s work is to confront an unspoken violence, one that does not merely belong to the past but continues to ripple across time. The water is not just an element; it is an unwilling witness, holding within it the voices of those it has carried, unwillingly or otherwise.

The Architecture of Loss

“There is where they tossed his body from the rooftop.” Dina Salem’s ‘Here and There’ is not about the past—it is about a present that never stops repeating itself. The Nakba did not end in 1948; it persists in the burning markets, in the homes stolen and renamed, in the brutal continuity of colonial violence. The work is a reckoning with memory and resistance, refusing the linearity of history.

By refusing to historicize Palestinian trauma—because how can one archive something that never ceases?—Salem forces us to confront a rupture that is never allowed to close. Her work does not romanticize suffering; it does not ask for pity. Instead, it asserts: “Only through resistance does the future unfold.”

To look at ‘Here and There’ is to recognize that for Palestine, the past is not a museum—it is an unfolding catastrophe, one that will only end when liberation does.

Jasmine and the Fragile Freedom of Night: Abeer Aref’s Poetic Resistance

There are freedoms that only exist in shadows. In ‘In My Nights, Jasmine Blooms,’ Abeer Aref captures the fleeting sense of liberation found in nighttime walks through Amman. Jasmine, which blooms only at night, becomes a symbol of this ephemeral freedom—a contrast to the constraints of her homeland.

Her black-and-white photographs dissolve into blurred impressions, evoking the uncertainty of memory. The scent of jasmine lingers in the air like a ghost of belonging—just as personal histories, too delicate to hold, slip through the fingers like fog.

Through poetic fragments, Aref constructs an elegy for displacement. Her images and words recall a mother’s warmth, a home left behind, a longing that refuses to settle. If freedom is temporary, then so is the jasmine’s bloom. But even in its brief existence, it marks the air, leaving an imprint of something once real, once beautiful.

Faceless in the Collective: When Women Become Symbols

Aceh, Indonesia: a place where a woman’s body is not her own, where identity is erased behind mandated veils, where control is woven into the very fabric of daily life. In ‘This Is Us,’ Riska Munawarah turns the facelessness imposed upon her into a haunting visual protest.

Through archival images and faceless portraits, she documents how clothing became law, how individuality was sacrificed for the collective, and how even within families, silence can be enforced as rigorously as the state’s dictates. But in resisting this erasure, Munawarah’s work does something powerful: it refuses victimhood. These images do not plead for sympathy; they reclaim agency.

The faceless women in ‘This Is Us’ are not passive. They are symbols of endurance, of quiet defiance, of a generation caught between cultural heritage and the fight for autonomy. In capturing their restricted world, Munawarah does something remarkable: she makes the invisible visible again.

The Laws of Ruins: Memory as Resistance

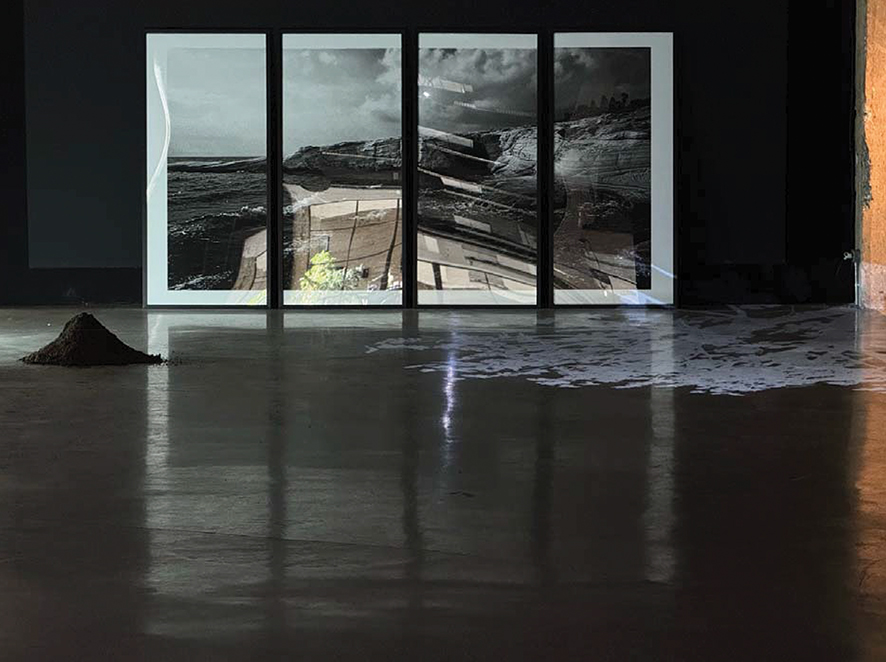

What happens when a ruin is forgotten? What does it mean when history is buried beneath the ground, unseen and unclaimed? In ‘Laws of Ruins,’ Marianne Fahmy brings Alexandria’s ancient water cisterns back into view, intertwining them with the revolutionary writings of Arwa Saleh.

Saleh, a leader of Egypt’s 1970s student movement, wrote of the movement’s failure in the 1990s—her words, like the cisterns, are fragments of an abandoned past. By pairing them together, Fahmy constructs a layered meditation on history, activism, and erasure.

Her work forces us to ask: Is a ruin still a ruin if no one remembers it? Is a revolution truly dead, or does it simply await resurrection? In an era of manufactured forgetting, ‘Laws of Ruins’ insists that memory itself is an act of defiance.

A Question of Survival, A Question of Future

The exhibition text opens with a provocation: “I wonder: What is so dear to these artists that it drives them to speak up? I wonder the same about myself. I wonder the same about you.” It is an invitation. But it is also a challenge.

What is dear enough to you that you would risk everything to defend it? Your home? Your language? The right to exist as yourself, without fear? ‘Something Very Dear’ is not just about the artists—it is about all of us. It is about what we are willing to fight for, what we are willing to remember, what we refuse to let be taken from us.

In Tbilisi, a city shaped by layers of history and resistance, this exhibition lands with the force of a reckoning. For two months, from March 13 to May 13, the Tbilisi Photography & Multimedia Museum becomes a site of confrontation—a space where stories refuse to die, where memory is sharpened into a weapon, where art is no longer just art, but survival itself.

And so the question lingers: What is dear to you? And how far would you go to hold on to it?

By Ivan Nechaev