First printed in Investor.ge

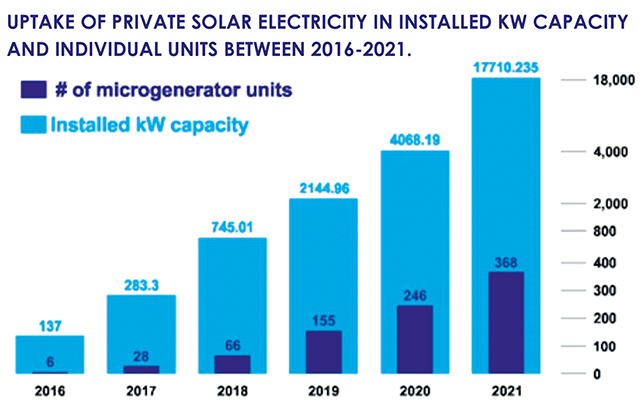

The sun shone unexpectedly bright on Georgia’s nascent private solar power sector in 2021. Data compiled by the country’s power regulator show growth of 335% in installed capacity of rooftop solar over the past year. But there are concerns that upcoming competitive power market reforms and questions of grid stability could bring this solar flare to an abrupt halt.

Self-proclaimed ‘renewable energy enthusiast’ Tornike Darjania certainly hopes this won’t be the case. When he opened his solar panel installation business Helios Energy in 2017, he did so ‘for fun, because we loved this technology.’ The company’s motto ‘Here comes the sun’ was anything but a forecast of explosive growth some five years down the line. “But now that the industry is on the cusp of developing something really special, to lose our momentum would be a real shame,” Darjania says.

It would be a shame. Georgia has been struggling to maintain a high share of renewables in its domestic power consumption mix. Data from Georgia’s Electricity Market Operator (ESCO) show that in 2016, approximately 81% of the country’s consumed electricity came from hydro. By 2020, that number had sunk to 65%, mostly due to growing imports and thermal (gas) power plant production. And while private solar isn’t the panacea to the country’s energy woes, it can have a sizable role to play in the country’s sustainable future.

Ongoing debates about what that energy future should look like are at the heart of what fueled last year’s growth in solar. Many companies placed their bets on the future of energy being a cheaper one after electricity price hikes in Georgia at the beginning of 2021 practically doubled the energy tariff for commercial consumers to more than 30 tetri / kWh. Interest in private solar power as a cheaper, more sustainable alternative has since soared amongst firms.

Households meanwhile have been less tempted. For them, solar PV units still entail substantial investments and the financial incentives are not strong enough; residential power consumers remain shielded from 2021’s price hikes (which raised the tariff from around 20 to 26.5 tetri) by a government subsidy.

Yet another group of solar buffs hopes the energy future is a participatory one. To encourage the use of privately owned renewable energy sources, Georgia employs a net metering mechanism, a system in which microgenerator owners can sell their surplus energy onto the grid, and are credited in kind or cash at the end of a 12-month cycle. Owners of solar power units with a generation capacity of up to 500 kW are allowed to participate in the net metering scheme, and this too has encouraged uptake, particularly among large businesses.

However, these benefits were paused last summer without much warning, and there is talk of a further scale-back on the benefits of the net metering system. While the system of credit in kind has since been restored and a new price schedule for prosumers will be announced in the coming months, solar power unit owners have expressed disappointment at the lack of clarity governing the fate of the mechanism, even leaving some questioning the benefit of their investment. Meanwhile, businesses in PV unit installation are warning that over-regulation could crush the industry before it has the chance to get off the ground.

It’s not all sunshine and reimbursement

Changes to the net metering system are a part of a series of changes surrounding ongoing power market reforms, Georgia’s obligations to the EU’s Energy Community Secretariat, and concerns of grid safety.

As Georgia moves towards the introduction of competitive power markets, a consensus on how to incorporate the net metering system has yet to be reached. The most immediate problem faced by net metering has been ‘unbundling’, a process which seeks to create a more competitive, less vertically-integrated power market.

Unbundling has obliged the country’s two distribution system operators (DSOs, Telasi and Energo-Pro Georgia) to separate the management of their supply (purchase and sale) and distribution activities. Unbundling took place in the summer of 2021, and the new market rules have it that only supply companies have the right to purchase and sell electricity, leaving distribution companies wondering how they will be paid for shuttling energy back and forth between microgenerators and energy supply companies.

Moreover, energy market prices for the commercial sector will soon be deregulated, and there is as yet no agreement what the rate of compensation should be for prosumers (i.e., owners of microgenerators who sell their excess energy back onto the grid), given the new costs that will be shouldered by DSOs. The former rate was the average price of electricity on the regulated wholesale market.

This impasse has left the system in limbo, causing much discontent amongst private microgeneration owners. One such owner, founder of the Bazaleti Green Engineering Center Zaal Kheladze, told Investor.ge that since these changes, his organization has lost out on compensation he claims is due to him given his PV unit’s excess yearly production.

“But it’s not just about the money. It’s about the lack of communication, and not knowing what I can expect. As a power project advisor, how can I tell a client to invest in this technology, not knowing how it will operate in the future?” Kheladze asks.

How these issues will be addressed remains to be seen. The Georgian Energy and Water Supply Regulatory Commission (GNERC) says it is now beginning work on a long-term vision of what ‘self-consumption’ might look like in Georgia, noting its readiness to engage with all stakeholders in the process.

But there are legal challenges which will also be faced by net metering, GNERC warns. Georgia is obliged to implement the Energy Community Secretariat’s Fourth Clean Energy Package, which holds that “net metering schemes…[negatively impact] the transparency and cost reflectivity of network charges […] and should be available only as an incentive to boost small-scale renewable self-consumption during the initial phase of its deployment and for a limited period of time.”

The deadline to harmonize with this legislation is January 2023, though GNERC says it is hoping to retain the net-metering system until 2026 as an exemption.

The list of issues to be addressed goes on: self-consumption as a trend may test the financial viability of DSOs, who are faced with the prospect of collecting fees from fewer customers over time for their distribution services. This could in turn translate into price hikes for other customers to cover DSO costs. Grid stability and balancing capacity also need to be addressed due to the element of unpredictability added to grids by renewables. This will entail still more investments in new, stronger transmission lines.

These concerns have already become very real for sun-rich locations such as Cyprus, Greece and California.

The sun always rises

These questions are technical, but the issue is of no small importance.

A USAID Securing Georgia’s Energy Future program spokesman told Investor.ge that self-consumption is a trend that cannot be ignored, and will have a role to play in the future of the country’s energy security and independence.

“The concept of ‘energy citizens’ has received increased attention in recent years, especially in the EU, where the potential for private and community generation has alerted states to the need to prepare for significant percentages of their population becoming ‘energy producing citizens’, which will entail serious legislative action and grid investment”, the spokesman said.

The challenges private generation will pose to the energy system are real, businesses in the sector conceded while speaking to Investor.ge, but noted it is too early to be imposing limitations, as the grid’s capacity to absorb private solar power generation is nowhere near its potential. In the meantime, they say, the benefits to be had from the renewable energy source should be encouraged.

In Georgia, the limit to microgeneration capacity on the grid currently stands at 4% of peak load. In Tbilisi, peak load is about 550-600 MW, while there is about 10 MW of installed solar capacity in Tbilisi (a tad less than 2%). Without the use of battery storage systems, which would increase the resiliency and capacity of the grid but remain financially non-viable for Georgia at this point in time, grids can accommodate up to 10-12% of peak load generation coming from microgeneration resources.

“We should tread with caution at this point in the development of the sector,” electricity solutions company Insta General Manager Sandro Bakhsoliani says, as “[the sector] is just getting off the ground, and private use solar can meaningfully contribute to the country’s goals of energy security and independence.”

An important step to ensuring the smooth integration of the burgeoning private microgeneration industry, Bakhsoliani adds, will be partnerships of public and private investment in making the renewable energy future a reality.

“It will, of course, have to make commercial sense. But the government should be involved in this endeavor on some level. This is what already happened in Germany nearly two decades ago when solar was just taking off there, and the government was really able to kick-start the process. Talk about foresight! Who will ultimately shoulder this responsibility is clearly an issue which needs more attention,” Bakhsoliani told Investor.ge, noting that interest in solar is only likely to grow as electricity prices do, which may occur at a rate of as fast as 10% every two years on average, he forecasts.

“Hopefully, we will find agreement on these issues in the coming months. We have great momentum right now and I hope Georgia can keep it up. Georgia can be one of the leading countries in the world in terms of sustainable and green electricity generation. We have the abundant natural resources to do so. It’s very important for us not to drop the ball now,” Bakhsoliani says.

Helios’ Darjania concurs, and adds that it is important not to lose sight of the ways in which renewable energy sources such as solar can also contribute to strengthening the grid. For example, they could increase electricity supply in local rural areas, relieving transmission lines of the tension which comes from having to transmit electricity long distances with too little power.

Darjania stresses that regulation should be gradual and slow, so as not to stifle the emergence of the sector, and should be fact and figured-based.

“‘Solar is good’, they say, ‘but can be a problem if there’s too much of it.’ Well, what does ‘too much’ mean? That is the question. We will be happy to sit down with all stakeholders and talk, but without imagination, without numbers that exist only on paper,” Darjania says.

Tidings on the market remind Darjania of a Georgian proverb: “‘A man was afraid of wolves, so he killed all his sheep.’ The situation is the same now: we are rightfully cautious, but because of that we are saying no to development. I understand we are now in the new reform process. But it’s important for micro generation, net metering, solar, wind and all of these technologies to find their place within it.”

Energy- Global Facts and Figures (Source: UNDP)

One in 7 people still lacks electricity, and most of them live in rural areas of the developing world.

Energy is the main contributor to climate change, it produces around 60% of greenhouse gases.

More efficient energy standards could reduce building and industry electricity consumption by 14%.

More than 40% of the world’s population, 3 billion, rely on polluting and unhealthy fuels for cooking.

As of 2015, more than 20% of power was generated through renewable sources.

The renewable energy sector employed a record 10.3 million people in 2017.

By Josef Gaßmann for Investor.ge