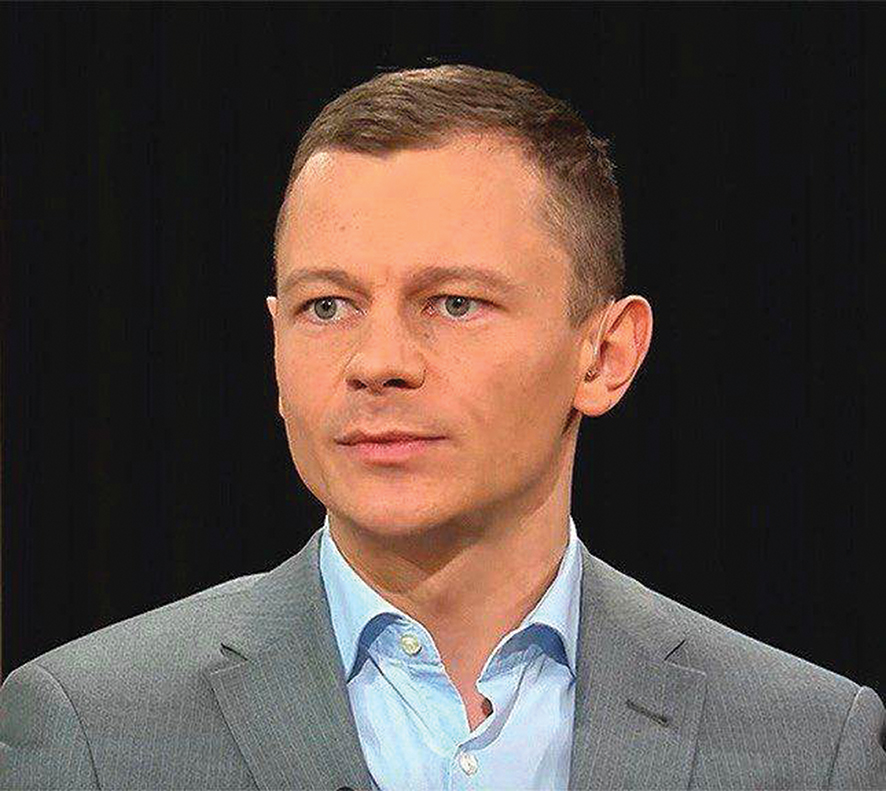

Pavel Slunkin, a Belarussian diplomat and political analyst, is currently a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Prior to joining the ECFR, he worked for the foreign ministry of Belarus. Pavel participated in the Minsk talks and worked as a political analyst at the embassy of Belarus in Lithuania. In 2020, he resigned in protest over the rigged elections and violence against the Belarusian people. Radio Free Europe / RL’s Georgian Service sat down with him to discuss the comparisons being made ever more often between Georgia’s future and Belarus’ past and present.

“There are similarities and parallels between the two countries, but I would rather begin by pointing out the biggest difference between the two: While Belarus has been under Lukashenko’s dictatorial rule since its independence, and has been turned into a totalitarian state, one where going against the regime has become significantly harder over the years, Georgia has seen an opposing trend; it has a history of democracy, and strong institutions.

“Belarus was never pro-Western, even if Lukashenko had periods where his relationship with the West improved, while in Georgia, people actively demand that the country moves toward becoming an EU/NATO member state.

The government does not have the same reach, the same amount of resources. You still have the opposition, you still have a say in parliament, you still have democracy

They see the threat; they see that the government might take the country in the opposite direction, and they are ready to fight it.

“I think the danger is that Georgia might become similar to Belarus in future, and that is what’s at stake here; that is what people are essentially protesting against, not merely a piece of legislation.

“With that said, there obviously are similarities. One would be the polarization of society, which both in Belarus and Georgia is being encouraged and manipulated by the governments, the “you are either with us, or against us” approach. So, obviously, they do not try to reduce the polarization; on the contrary, they play on it. Another similarity would be threatening people with war and posturing as the only guarantor for peace. Ever since Putin’s full invasion of Ukraine, Lukashenko has been telling us, “Look, Belarus is not part of this war, and if you want it to remain so, then I am the only one who can guarantee it. I am a peacekeeper; I will keep you out of the war.” And, obviously, he accuses all his democratic opponents of wanting to drag Belarus into the war. I think Georgian Dream is doing pretty much the same thing, with this nonsensical narrative about the “Global War Party” and accusing the opposition of wanting to open a second front in Georgia, which is just crazy.

“And, obviously, the repressions: All that you are now seeing in the streets in Tbilisi, we saw that in Minsk a few years ago. I would dare to say we saw far worse than what’s happened in Tbilisi, as they were far more brutal in Belarus. Intimidation, beatings, arrests, using the so-called Titushki and so on. We too had a phone intimidation campaign, when they would call and threaten and intimidate people. Ironically though, they were also intimidating their own people, to ensure their loyalty: Special services would send threats to high ranking government officials, as if they were sent from the protest leaders: “When we come [to power], you will be dead, we will kill your children, we will take everything from you, you will pay”. Lukashenko would use this to instill loyalty: “This is what will happen if you will try to defect, if you don’t stay on board. I am the only one who can save you.” And many people did believe that these messages were sent by the democratic activists.

Why did the protests and resistance fizzle out in Belarus, and can the same happen in Georgia? How did Lukashenko break the people?

My answer would be that, first of all, Lukashenko was more powerful. Far, far more powerful than Georgian Dream is. He had all the state resources, the apparatus, the siloviki, the army, very well equipped and loyal special forces and, obviously, Moscow’s support – Moscow sent troops to the border between Russia and Belarus, essentially saying that if something gets out of control, if the protesters are seen to be winning, we will invade. I know for a fact that Moscow was also intimidating our state officials – deputy prime ministers, ministers, other officials who had resources, political power, not to bail out, not to support the protests or oppose Lukashenko, telling them they would pay a bloody price if not, and so would the country. That worked. It ensured that very few top ranking officials resigned. And, in parallel, they were ramping up the repressions and crackdowns. In the first weeks, when they saw that there were hundreds of thousands of people, so they couldn’t effectively disperse or beat them all up, they arrested just a few. The next week, five arrests became 100 arrests. Then they started the hunt – they arrested the leaders first, then they raided the offices of political parties, then intimidated and hunted down whoever remained, or whoever might emerge as a new leader. I was there – I can see all of it even now, as if there was a picture in front of me. They bled the protests dry. You are there, it’s a peaceful protest, you are making sure that the world sees that you don’t want any violence, you are unarmed. Then they close in and you see a Kalashnikov pointed right at your face. What can you do? The only thing we could do is to show that there were many of us, that we were the majority, and we weren’t going away. And the protests lasted a long time, months, but, bit by bit, the arrests, the crackdowns, the intimidation took their toll; they chipped away at us, bit by bit. Even with the hindsight, I just don’t see any way we could have won. Really, this was a battle that couldn’t be won.

The sanctions will probably make Georgian Dream even more dependent on Moscow than they are now

With Georgia, it’s different, it’s not yet the totalitarian dictatorship that Belarus already had in 2020; the government here does not have the same all-encompassing reach, the same amount of resources. You still have the opposition, you still have a say in parliament. Simply put, there is democracy in Georgia. And as numerous as the protests are, I think even more people are staying at home, not going to protest in the streets, but still not government supporters. They share the values of those who take to the streets, but they are still at home. You should find creative ways to involve them in the protests.

Based on the Belarus experience, long term strategy and vision are important. We come out on the streets, we protest, we know what we want to achieve in general, but we don’t know how. I think that could become a problem in Georgia, as I see the numbers are decreasing. In Belarus, people would ask themselves: So we did what we could, we tried, and nothing changed. People stop seeing any reason to come, just because it’s a risk with no results. I hope that doesn’t happen in Georgia, but there’s a chance it might.

In Georgia, we worry we might see Russian guns and Russian troops heading here to ensure “stability.” What do you do with such an immediate threat?

This is exactly what happened to us. People knew that even if we won, there were tens of thousands of troops near the border with Russia and they would send the troops over. And this was a very destructive point for most of society, because the way people saw it, yes, we had a chance to win against Lukashenko, but when Russia got involved, then we realized there was nothing we could do; we would lose.

How realistic that scenario is in Georgia’s case, I don’t know. My guess would be that Moscow can help Georgian Dream without getting actively involved, just sending over some people, some resources, without resorting to invasion to guarantee that the government wins and stays. What should the Georgian people do in this situation? I’m afraid I don’t have any good advice. Russia spoils every single spark of democracy in its neighborhood, that’s the reality we live in.

Could the West perhaps play a more active role in preventing this?

The West could play a more important role. And they should have done this already, when Georgian Dream started politically motivated arrests in previous years. They weren’t active enough. The talk about limiting visa liberalization and personal sanctions should have started before. Now it might already be too late, it might be that Georgian Dream, much like Lukashenko when he was sanctioned, think: We will survive this, we’ll weather this storm. In a way, the sanctions will probably make Georgian Dream even more dependent on Moscow than they are now; will make them outright puppets of the Kremlin, much like Lukashenko. So I’d probably go for some sort of a balanced, compromise approach – something that the recent bill from US Congressman Wilson seems to be going for. The compromise might not be a victory for either side, but it will prevent even worse outcomes, including the one where Russia gets involved.

Interview by Vazha Tavberidze