Read Part I

Read Part II

Read Part III

Literature is the only branch of art that is enclosed within its own linguistic limits and is accessible to the bearers of a definite language only. But any estimable piece of literature, and especially poetry, contains a powerful charge that encourages an appreciative translator to bring the masterpiece to the notice of other nations, thus making it dear and important to them. Therefore, the translator’s work and the act of translation itself appear to be caused by an inner compulsion that what is felt and reasoned in one language should pass the linguistic boundaries of one tongue and become the property of as many nations as possible.

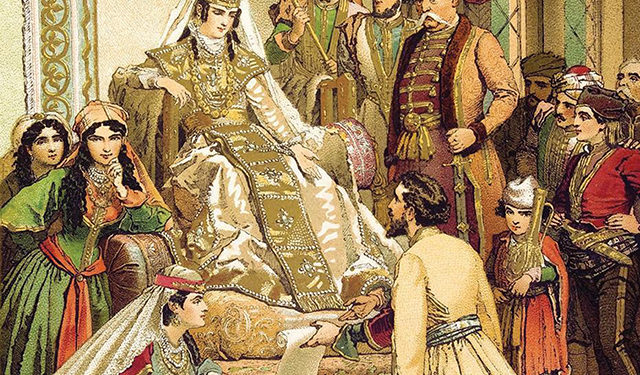

Rustaveli composed the poem “The Man in the Panther’s Skin” somewhere between the end of 12th century and the very beginning of the 13th, but it was first published in 1712 by King Vakhtang VI in his newly founded first Printing House in Tbilisi. The publication comprised 1587 quatrains with enclosed comments and study by the King himself. Very like to Shakespeare, not a single page of Rustaveli’s original manuscript has survived. The manuscript according to which Vakhtang VI would have prepared his publication has yet to be found. The earliest dated manuscript of the poem shows the year 1646. Scholars assume that when rewriting and composing manuscripts of the immortal poem anew, some compilers took liberties in altering or extending the existing texts- there are manuscripts of the poem, created in the 18th century, where the number of quatrains is over 2300, much prevailing the number of quatrains in the 1712 publication. In Marjory’s lifetime, more than ten publications of the poem appeared. Marjory Wardrop was a big collector of Rustveli’s publications, manuscripts and studies of the poet. Of course, the 1712 publication is at the top of her bibliography.

Marjory Wardrop was a big collector of Rustaveli’s publications, manuscripts and studies of the poet

As a translator and translatologist, I have been investigating the original text of Rustaveli’s poem against its five English translated versions. Studies show that in spite of the fact that Marjory Wardrop created only a prose version of the poem, she is the “winner” not only through her precise, laconic and trustworthy rendering, but through the scholarly attitude of the research she conducted during her work.

Today, experts of translation agree that text interpretation, especially when supported by philological research, is a leading point in translated matters. Text interpretation, plus its artistic realization, that’s what creates a duly successful translation, though the level of interpretation much depends on the quality of translator’s readiness to grasp the values of a masterpiece. Besides, the current attitude of translatology has one more demand towards translators: any translator should be at least bilingual and must achieve a profound knowledge of the source language, i.e. the language of the original. Marjory Wardrop anticipated the progressive attitude and developed meticulous research in the 19th century, when translatology as a branch of philology had not yet been established. But first of all her research and translating activities were preceded by the process of learning the Georgian language, its culture and history. Only through such dedication was Marjory capable of feeling not only the music of the words, but the music of thoughts implied in Rustveli’s text.

There is much to be said and showed concerning Marjory Wardrop’s version. The author of these lines finds it necessary to illustrate the skills and sensitiveness of the translator at least through one example.

The final stanza of the poem that precedes the prologue, offers the main credo of successful rule in the country. Here, we offer the Georgian original text of this quatrain according to the 1712 publication, alongside its linear translation:

ყოვლთა სწორად წყალობასა, ვითა თოვლსა მოათოვდეს,

ობოლ ქურივნი დაამდიდრეს და გლახაკნი არ ითხოვდეს,

ავთა მქნელნი დააშინეს, კრავნი ცხვართა ვერა სწოვდეს,

შიგან მათთა საბრძანისთა თხა და მგელი ერთად სძოვდეს. (1664)

Equal mercy fell on everyone like snow,

They enriched orphans and widows and the poor did not beg,

They terrified evil-doers, the lambs could not suckle the ewes,

Within their domain, goat and wolf graze together.

It is obvious that the phrase “კრავნი ცხვართა ვერა სწოვდეს” – “the lambs could not suckle the ewes” by the end of the third line comprises very strange content, absolutely contradicting the high ideals presented by the quatrain in connection with the regulations in the state. Did Marjory share the above shown content according to the King’s publication? Did she subdue her interpretation to the published version that resonates until now and frequently appears in print? Here is Marjory’s translation of the quatrain, which reads as follows:

They poured down mercy like snow on all alike,

they enriched orphans and widows and the poor did not beg,

they terrified evil-doers; the ewes could not suckle the lambs,

within their territories, the goat and the wolf fed together. (1571)

Through the phrase “the ewes could not suckle the lambs” Marjory created the following content: the ewes must not feed on the lambs, but on the contrary, the lambs must get their nutrition from the ewes, that also has symbolic implication. To our great surprise, through that small but important detail, Marjory is again the winner, when compared to other existing English versions. We may assume that the translator who did not follow the King, followed the poet and his main conceptual attitude, thus creating a content that fully fits the poet’s credo of successful ruling of the country.

Through such dedication she could feel not only the music of the words, but the music of thoughts implied in Rustveli’s text

Much later, in the 1950s, Rustveli’s poem was published under the editorial work of eminent Georgian scholars: A. Shanidze, K. Kekelidze and A. Baramidze, where the third line reads as follows: “ავის მქმნელნი დააშინნეს, კრავნი კრავთა ვერ უწოვდეს”, that can be rendered in English as: “lambs could not suckle from lambs”, again confirming Marjory’s attitude, talent and intuition in the matter of translation.

To finalize, I would say the following:

Some lives are lives; some are but fairy-tales. Even in a fairy-tale, immortality is an outcome of a life, lived by a mortal, but full of love, faith, courage and devotion.

By Innes Merabishvili

*Innes Merabishvili is the Head of the Chair of Translatology with MA and PhD programmes at Tbilisi State University