Russia attempted to intimidate Georgia through war and give itself the ability to continue to intimidate Georgia by manipulating the situation of the borders. But Georgia, because it fought so well during those five days, maintained its independence. Saakashvili didn’t fall, he lost an election later and left power peacefully, – Ambassador Dan Fried, then-Assistant State secretary for Europe, tells Radio Free Europe’s Georgian Service. “Right after the war, the US helped organize an international donors conference which gave over $4 billion to the Georgian economy, which was enough to keep them afloat. Georgia maintained its independence, but it lost territory.

“The situation was similar to that of Finland after the Winter War, which maintained its independence; the Finns to this day are proud of what they did. They saved their country. The Georgians also saved their country, but Georgia’s geography is not great and Russia has the ability to continue to intimidate Georgia,” Fried notes. “The problem, of course, is that the current Georgian Government does seem frightened, or pretends to be frightened, of what the Russians can do. But I don’t want to be harsh, because Russia is an aggressive power and Georgia is in a vulnerable position.

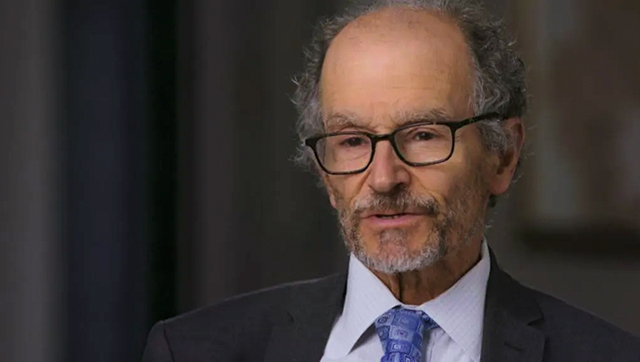

“Internationally, Putin got away with the August War, and I say that without pride or pleasure. The Bush administration, after the war, understood that its policy of reaching out to Putin had failed. But then Obama people came in and pressed the reset button. I don’t mean to be critical. Mike McFaul is a serious, honorable, knowledgeable person. He’s a good guy. And I understand why he did it. But it didn’t work, as he will acknowledge, because he’s honest. Just like our policy in the Bush administration didn’t work. And it meant that Putin got away with it. And then six years later, in 2014, he attacks Ukraine, thinking he can get away with it again.”

What did the August War mean to you?

Those of us who were involved in US policy toward Georgia and Russia remember every hour of every day of that war. I remember speaking on the phone to Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Karasin. I remember speaking to Condi Rice. I remember the trip she took in July 2008 to Tbilisi, and what she said to Saakashvili, I remember the discussions I had with Eka Tkeshelashvili, Georgian Foreign Minister, on the Thursday afternoon. I remember the images of the Russian tanks rolling through. I remember the trip to Tbilisi, but first to southern France to work with the French on improving their not terribly good six-point peace plan. I remember being on the phone with the French National Security Adviser while I was in the room with Condi Rice and Saakashvili niggling about the same thing. I remember it very well. It meant in a larger sense that Putin was willing to go to war to defend his version of the Russian Empire. It’s a lesson we have all learned with respect to Ukraine, but we learned it first with Georgia.

Any regrets, missed chances, when you look back at it? Anything that could have been handled better?

Sure. We were worried in the run up to the war, but we weren’t worried enough. I’ll give you a specific example. I was the assistant secretary for Europe. The next person up the chain was Undersecretary Bill Burns. He’s now head of the CIA. Condi Rice told me that she wanted Burns to go to Berlin and confer with the Germans and talk to the Russians to head off the war. In retrospect, she was late. We should have escalated sooner than we did. We knew what was coming, but we were slow to believe it. We didn’t think the war would actually happen. People were going on summer vacation. Rice was at a resort in Virginia, I was away in Arizona. You asked what we could have done differently. The fact that we were on vacation indicates that we thought we had more time than we did.

Would it be too heavy handed a judgment to say that you guys didn’t take it seriously enough?

Look, you’re a Georgian, what am I gonna do? Georgia has suffered. I’m not going to criticize the way you criticize us. You have every right to be critical. And the United States was right, but we were too slow. We were at a five or a six, we should have been at a nine on the urgency scale. Part of the problem was that the US analytic community didn’t think Russia would attack. They couldn’t quite understand that Putin was an aggressor. I remember on the Monday [the War started on Thursday], at the senior staff meeting, I said to Condi Rice, “I have a very bad feeling about this week, things are not going well. Putin could attack.” She didn’t believe me. Nobody in the wider analytic community shared the view. It was my gut feeling, but even I didn’t take it seriously enough to stay home. We thought there’d been crises before, a lot of them, and we thought this was just another one, where the Russians were trying to intimidate Georgia, but they wouldn’t attack.

Now, I don’t want to be too hard on us. After all, President Bush, in the end, convinced Putin to pull back. We sent US planes to fly the Georgian first brigade back from Iraq, and ships. We informed the Russians we were flying them because we didn’t want them surprised. They said they couldn’t guarantee the safety of our aircraft, which was a veiled threat. And we said we’re going in anyway. And they backed off.

On the Monday, the Russian tanks were rolling. And the Georgian lines were broken, and the Georgian army was in retreat, and it looked like they would move on to Tbilisi. Ambassador [John] Tefft and I were having multiple calls a day, and Tefft said, “Dan, you realize where our embassy is? On the main road north of Tbilisi. The Russian army could be here tonight.” He was absolutely calm, absolutely focused, and he understood what was happening. Matt Bryza, my deputy who had flown out to Tbilisi, was in the presidential palace, with [then Swedish FM] Carl Bildt. They thought it could be attacked, but they weren’t going to leave. They had to show personal solidarity, which actually took some courage because that would have been an early target, and they didn’t care. So, we did the right things, but you didn’t ask what we did that was right. You asked what we did that was wrong. And I feel honor-bound honestly, to say so.

It has almost become a catchphrase that Saakashvili was “provoked.” The Ukrainians didn’t fall for provocations in 2014 or in 2022, but it didn’t stop Putin from seizing Crimea, without firing a gun, or this war now.

Putin wanted his war against Ukraine. And even though the US successfully exposed all of Putin’s provocations, he went in anyway. So, to blame Saakashvili [for the August War] and say, “well, he fell for the provocations, therefore the war’s his fault,” is nonsense. Putin would have gone in anyway, but, because Saakashvili fell for the provocations, the Germans and others had an excuse not to be as supportive as they should have been.

We didn’t think the war would actually happen. People were going on summer vacation

The Russian proxy forces were shelling Georgian villages, and we warned Saakashvili in advance not to move. Condi Rice did it when we were in Tbilisi in July. I did it that very day. But I understand that they were provoked, and let’s just repeat: Putin would have attacked anyway. The problem is that you had the Germans and the French able to blame Saakashvili and half-excuse Putin. And their reaction to the Russo-Georgian war was much weaker than to the Russo-Ukrainian war.

But if Saakashvili hadn’t fallen for the provocation, and the Russians had attacked anyway, would the German and French position have been very different? I’ve been thinking about this for years. I’ve been critical of Saakashvili for his decision, but, let’s be clear where responsibility really lies for this war: it is Vladimir Putin.

How wise was it to leave the negotiations to the French in 2008? How satisfactory where the results?

[Laughs] I remember when we were in the south of France, taking a look at the six-point ceasefire Sarkozy had negotiated as the presidency of the EU. The line of Russian controlled bisect in Georgia was a mess. Condi turns to me, and says, “the French invented cartography. Didn’t anybody read a map?” Which is her version of being really angry. Sarkozy’s six-point plan needed to be fixed. But we can’t blame him or the French, because even if the plan had been better, it might not have made a difference. The Minsk accords had their faults, though they were much better than the six-point plan, but Putin did not respect them. He twisted them, he projected onto them a meaning that they didn’t have and waited for people to accept his nonsense interpretation. The flaws were not critical, because Putin would have ignored a better document anyway. The document stopped the fighting, which is what Putin wanted. We managed to claw back some of the worst provisions and save Georgia’s integrity. The flaws of the six-point ceasefire were not critical to the outcome nor the future.

Would it not have been better to have an effective plan, with some mechanisms ensuring its implementation, something that you could then stick to Putin?

Yes, but the difference would have been tactical, not strategic. I wish it had been better. But look what happened with the Minsk accords. It was better, but it didn’t make any difference. In the end, the critics, Georgians, Ukrainians, Poles, Estonians Lithuanians, who tell us the only way to deal successfully with Russia is from a position of strength, do have a point.

On the subject of documents of debatable merit, how well did the Tagliavini Report handle its mission?

I wish the document had been clearer about where responsibility for the war lay. Ron Asmus and his book about the war did a very good job. I wish it had been a better report. I didn’t trash it- I don’t believe in intramural fights within the West unless I absolutely have to have them. We have to remember who the real enemy is. It’s Vladimir Putin and his system. I wish the report had been better. But as I said about the six-point plan, even a better plan, or even a better report, would have made a tactical difference, but not a strategic one. Therefore, I don’t want to spend time criticizing it except to say that I think it should have been clearer about where responsibility lies.

My view of the Obama policy is that it failed, but it was an honorable failure

Last year, you said the West was not united in 2008, so it opted for economic assistance as opposed to imposing sanctions on Russia. Was that the right move?

It would have been better to impose sanctions. But two problems: One, we weren’t as smart about sanctions yet. We learned how to do sanctions against Iran after 2008. And then we applied them against Russia. So, one, we weren’t as smart. And two, we would never have had consensus. The Germans and French would not have supported it, and had we tried, we would have lost – it would have been like the Bucharest Summit. Losing the fight on the map, we would have lost again twice in one year. That would have been bad. So do I regret we didn’t do sanctions? Sure. But there were hurdles we couldn’t get over.

And that eye-popping RESET button a mere seven months after the Georgia war – was that naivety? Wishful thinking?

I was there. Mike McFaul was the architect of the reset. I know him and I respect him. He was working for Obama, the election hadn’t happened. A lot of the Obama people were very critical of Bush’s handling of Georgia, half of them believed the war was Dick Cheney’s fault and he had egged on Saakashvili and some nonsense. McFaul was the foreign policy person. In his testimony to the Senate about the Georgian war, he blamed Putin. It didn’t help them politically within the Obama campaign, so he came up with the reset. And I said, “Look, Mike, I know why you’re doing it, and I’m not going to trash you for it. I’m not going to attack you because you’re doing it for the same reasons we did it, but we can do it better. You’ll fail for the same reasons we did. You won’t be able to accept Putin’s terms for a better relationship for more than a week.” Later, he admitted I was right.

What did Russia do to deserve this diplomatic debit?

The Russians were suggesting that we could get along decently. They weren’t aggressive toward Ukraine. Medvedev was the President, and though we were completely wrong, the Obama people thought he was more modern, more of a 21st century person, not a KGB person. My view of the Obama policy is that it failed, but it was an honorable failure. And by that, I mean that when Putin attacked Ukraine, they responded by resisting. They should have sent weapons to Ukraine. That was a mistake. I was on the other side of that policy. I’ll tell you who else was – Strobe Talbott, who had basically reached out to Yeltsin and was skeptical early on, and correctly so, about Putin. Talbott in 2000 thought Putin was bad news. He was right. Talbott wanted to send weapons to Ukraine. The Obama people said no, the argument they used was “an escalatory danger.” They were wrong. I’m not going to defend it. They were just flat wrong. We should have sent weapons. But at least they organized the sanctions. Those sanctions don’t look big now, but at the time, they were huge. It was an honorable failure.

Interview by Vazha Tavberidze for RFE