Nicolas Tenzer is a French academic, writer, editor, the current editor of the journal Le Banquet, and is the founding president of the Centre d’étude et de réflexion pour l’action politique (CERAP). He was a director of the Aspen Institute from 2010 to 2015. Radio Free Europe’s Georgian Service sat down with him to discuss the recent US intelligence leak, the West’s commitment to Ukraine, and Georgia’s stance on EU alignment.

Let’s start with the recent US intelligence leak – what impact is it going to have on the war?

It won’t make any kind of difference, because the strategy has already been decided by the US and allies. The real question here is up to what point the US and allies will continue to help Ukraine. For the moment, in my view, the allies remain halfway in support; they are contemplating, watching it from the outside. Basically, we are, in a way, spectators: of course, we continue to provide Ukraine with a lot of weapons, munitions, but we will only do so up to a certain point. And for me, this is a problem. From this perspective, the leaks don’t change anything, especially when they say that it will be very difficult for Ukraine to launch a new massive offensive to retake Crimea and so on – the question here isn’t whether Ukraine will be able to do so or not, the question is whether we’ll help Ukraine to do so.

It would be wise for the US and the allies not to buy into the Russian narratives about the so-called red lines, especially on Crimea. For 22 years now, Putin has been allowed to win all these wars. And since 2022, he’s not been allowed to do that. But having said that, there are also divergences in the West, not only in the wording, but also the implications: first, we said we had to defend Ukraine. Okay, good. Now, we are saying: we have to make Ukraine win. Okay. But you have two differences amongst the allies on what Ukraine’s victory actually means. For me, Ukraine’s victory entails the following: First, Ukraine must retake all its territories, including Crimea, no special status for Crimea; Second: full punishment for war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and crime of aggression, all four categories; Third: repatriation of all deported Ukrainians, the refugees, especially the children. The fourth thing is, of course, the reparations, Russia paying for damages, a seizure of all the assets, including the central bank assets. And the fifth would be security guarantees for Ukraine. By that I mean, a kind of Article Five + of NATO Treaty.

The second point of divergence is about the fate of Russia. For me, it’s important not only for Ukraine to win the war, but also for Russia to radically lose the war. And I think not only to lose in Ukraine, but also to lose in Georgia, to lose in Belarus, to lose in Syria, in Moldova, etc. And I think that’s absolute key point.

This total Ukrainian victory and total defeat for Russia you describe – Do you think it’s realistic and achievable?

Yes, definitely. Yes. I think it’s achievable. I am from the so-called realist school in international relations. Not the pseudo-realists, like Mearscheimer and co, that’s fake realism. The realist has to consider what is achievable. And if we consider the immensity of the US military powers, plus, of course, the military prowess of the UK, of the important EU countries, it’s achievable. I am not saying that we have to send troops, to capture Moscow. The victory in 2023 will not resemble the victory in 1945. We are not in this kind of scenario. But I do believe that we have certainly the means, if we so want – that is the question.

The real question here is up to what point the US and allies will continue to help Ukraine

In realistic terms, it’s militarily and politically achievable. What I don’t know is whether Mr. Biden or Mr. Macron and Mr. Scholtz really do have the will to do so. I’m not sure they have the full awareness of two things. First of all, the long lasting threat that Putin’s Russia or Russia with another guy, even if isn’t Putin himself, poses to the old world. The second is the immensity of crimes committed by Putin’s Russia for 23 years. When it comes to Russia, the crime is the message.

The crime is the purpose. The crime is the DNA of the Russian regime, not saying of Russia itself.

On the security guarantees you mentioned, Ukraine has been literally begging for them ahead of the upcoming NATO Summit. Do you think it will get them?

What would those look like? It could be NATO membership, a MAP offer. But we have to know that Article Five is not automatically triggered. That’s why I said “Article Five plus.” We must have a full guarantee that if Ukraine is attacked, again, troops will be sent there to defend it. Then there is the second thing, which isn’t necessarily an alternative to NATO, but which is probably the best way right now to offer security guarantees to Ukraine – we could station troops in Ukraine, NATO troops, from both the US and Europe, could be the UK, Baltic States, Poland etc., permanently stationed in Ukraine.

And speaking as a self-professed realist, how likely do you think that is?

Before the end of the war? I’m not confident, but after the war is finished, there will be no other way to seriously tackle the question of a security guarantee for Ukraine. If we don’t have troops on Ukrainian soil, NATO troops, how else could we achieve a guarantee of security for Ukraine? I see no other way.

President Macron’s recent visit to China was dubbed by many as a strategic blunder. Was that the case?

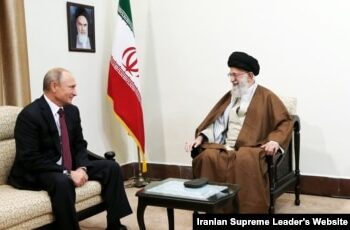

I think it was indeed a strategic blunder, because he seemed by doing so to be saying the security of Taiwan was not an EU concern. And basically to be wagering between the US and Europe on security. I’m not saying that we cannot disagree with the US: we have a lot of disagreements, trade disagreements, for instance, that’s perfectly normal. But when it comes to security against Russia and China – there must be a full unity. China will continue as long as it takes, as we say, to support, probably militarily also, Russia. The fall of Putin’s regime will be a disaster for China, because those kinds of dictators always fear democratic contagions, you know. And you see in the making a process of coalition between all the dictatorships, not only with China and Russia, but also with Iran, with maybe up to a certain point North Korea, some Arab states, Gulf states, etc. And there were suspicions that Macron was trying to find a kind of Third Way. It’s very dangerous.

When Macron says: “Being allies doesn’t mean being vassals” what does the Macron-led strategic autonomy entail and how realistic is it?

EU strategic autonomy isn’t a new concept, Macron certainly didn’t invent it- it was already used back in 2010s, well before he came to power. And it’s basically a polysemous concept. You have different kinds of meanings. Let’s take an example: Back in 2013, President Obama finally abandoned the very idea of having US red lines in Syria, because the Assad regime crossed that line – used chemical weapons, but Obama decided not to take action. The UK followed suit. France wanted to act – then President Francois Hollande said, “ we are ready to go and we are ready to strike,” but, unfortunately, France was alone. And France alone cannot take action in Syria.

The European fate of Georgia more precisely, will be decided in Ukraine

So, basically, strategic autonomy could be a very useful concept from this point of view, if the US doesn’t take action, whether it’s in Syria or in Ukraine, we must have the means. And on that Macron has a good point. That’s good. But if strategic autonomy means that visa-vie the great revisionist powers, namely Russia and China, we try to take a different standpoint, that will be a very dangerous division of the allies.

There cannot be strategic autonomy when it comes to the relationship with those kinds of powers. We must be very clear on that. And for instance, when it comes to Russia and China, the question is not to be aligned, but to have very candid, direct, and daily discussions with the US, but also with Canada, with Japan, with all our allies, to try to find a common ground.

All this talk about vassalage, autonomy, and so on represents an age-old dilemma for Georgia: throughout its history, the country had to navigate between and around the superpowers to survive. Where does Georgia stand now, as the government shows signs of growing resentment towards the US and the West in general?

Growing resentment could be an understatement, I would say. The real issue, in my view, is does the government have a true willingness to do everything necessary to join the EU? Or has it discreetly, without saying anything, abandoned all ideas to join the EU? You know, I’ve visited Georgia many, many times. I know that the Georgian people, at least the people in Tbilisi and in big cities, are in favor of the EU, NATO; they are in favor of democracy. And the problem is, does the government today support this claim? And I would say that basically, the fate of Georgia, or rather, the European fate of Georgia more precisely, will be decided in Ukraine. If Ukraine wins this war, and if Russia is fully defeated in Ukraine, etc., then certainly, I think the paths towards the EU and towards NATO will be greatly facilitated. But if we consider, for instance, let’s say unlikely and disastrous scenarios, in which you have a kind of victory for Russia, which is the full defeat of Ukraine, if Moscow still is able to retain some parts of the territories in Ukraine, then the anti-EU stances in Georgia, but also in other countries, will grow, they won’t be dissuaded. Because Russia will still be there.

It’s important not only for Ukraine to win the war, but also for Russia to radically lose the war, and not just in Ukraine, Georgia too

The narrative peddled by the government is that they don’t want to be dictated to by Washington or Brussels. What would you say to that?

EU membership is basically about compliance with common norms, it’s not a question of alignment. It’s not a question of vassalage. It’s a question of compliance: does the Georgian government want to join the EU? Are they willing to comply with those principles – human rights, rule of law, freedom of press, freedom of speech, which are the very DNA of the EU? The question here is: Do you want to join the club, and the club has some rules, or not? If you don’t like those rules, okay, goodbye.

Interview by Vazha Tavberidze for RFE/RL