By mid-autumn the Georgian capital once again became a meeting ground for the world’s stages. The Tbilisi International Festival of Theater 2025, long a point of exchange between East and West, presented an international program that made the city feel briefly like a laboratory of contemporary performance.

The festival opened earlier with Richard III by Gesher theater from Tel Aviv—an event we discussed in last week’s issue—but what followed, over the next 10 days, was a tightly composed sequence of works that treated theater not as escapism but as an instrument of inquiry.

The Georgian audience encountered, in succession, a British work that recasts the heroic quest as an inner psychological struggle; a Greek meditation on routine as quiet surrender; a Latvian film-performance in which Mikhail Baryshnikov lends a human face to the exhaustion of power; and an Israeli dance piece that imagines the body as a vessel of light.

In a year when theater everywhere faces the pressures of digital distraction and political fatigue, this program stood out for the way it trusted the stage — and the body on it — to carry philosophical weight.

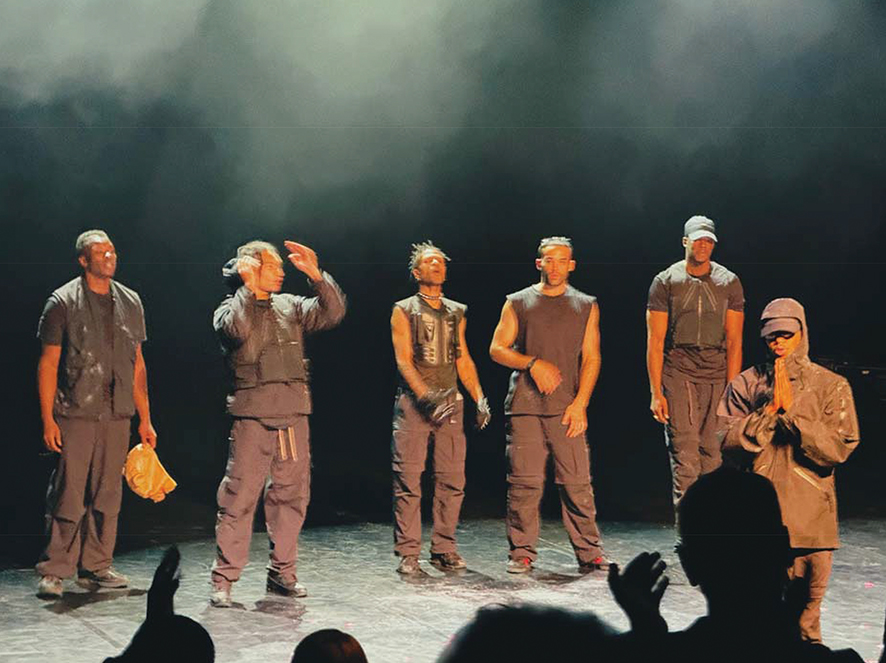

The Pulse of a Heroic Quest: TRAPLORD by Ivan Michael Blackstock (UK)

At first glance “TRAPLORD”, presented at theater Factory 42, has the energy of a club night: bass-driven sound, street-inflected movement, a sharp visual edge. Yet its hour-long arc unfolds as a contemporary version of the katabasis— a descent into the underworld in search of self-knowledge.

Choreographer and cultural innovator Ivan Michael Blackstock, who received the 2023 Olivier Award for this work, uses dance, spoken word, and theater as interwoven languages. The piece addresses what it means to grow up as a Black man in a society that projects menace onto you before you have even lived your own story.

Blackstock’s choreography fractures and recombines: explosive jumps break into weighted stillness; hands reach outward as if testing the air for permission. The text is sparse, less declarative than confessional.

The Siege of Ordinary Life: The House by Dimitris Karantzas (Greece)

Two days later the stage of theater Factory 42 was transformed into a nondescript urban apartment for Dimitris Karantzas’s “The House,” commissioned by Athens’s Onassis Stegi.

A man and a woman — never defined as couple, siblings, or flatmates — go through the rituals of a typical day: folding clothes, doing accounts, arranging the shopping. The gestures, at first merely domestic, acquire a ritualistic rhythm. The outside world exists only as a faint electronic hum.

Gradually one realises that the routines have become fortifications: a strategy to keep at bay the unarticulated threats beyond the apartment door. The piece suggests that the most pervasive violence of contemporary urban life is not spectacular but incremental — the slow erosion of agency by the sedatives of routine and image.

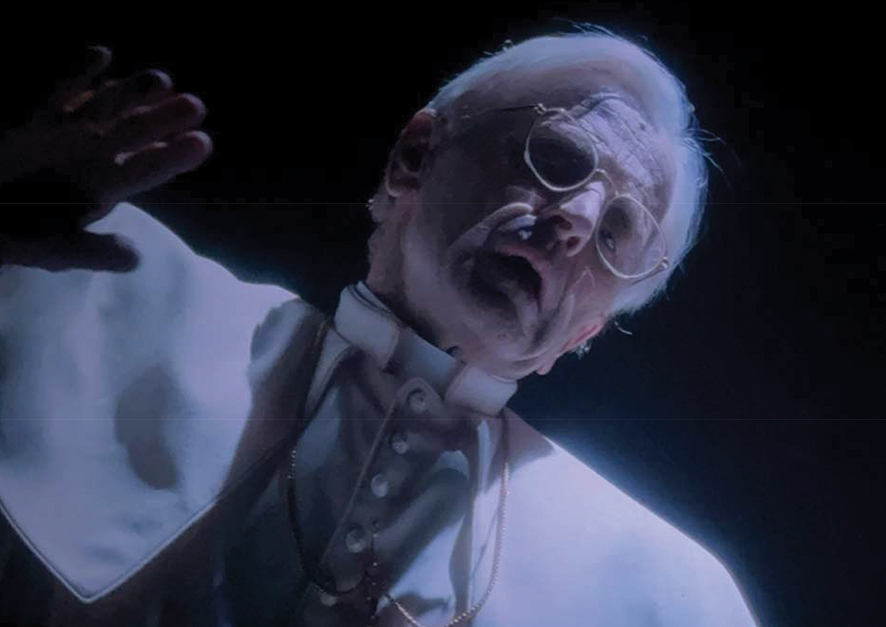

Authority in Decline, Seen in a Face: The White Helicopter by Alvis Hermanis (Latvia)

The festival’s marquee event came on October 2: Alvis Hermanis’s “The White Helicopter”, a hybrid of film and staged presentation, centered on the last day of Pope Benedict XVI before his 2013 resignation — the first papal abdication in six centuries.

Rather than exploring Vatican intrigue, Hermanis trains his camera — with cinematographer Andrejs Rudzats — on the face of Mikhail Baryshnikov, who portrays Joseph Ratzinger. The close-ups, often unflinching, turn the actor’s features into a topography of thought: furrowed lines as ridges of memory, eyes reddening as conscience tightens its grip.

The dialogue between the Pope and his secretary, played with measured dryness by Kaspars Znotinš, becomes a debate on Europe’s moral exhaustion. The production’s intellectual restraint is its drama: in Baryshnikov’s stillness one senses the solitude of a figure confronting the limits of inherited authority.

A Spiral of Light and Gravity: Mana by Noa Wertheim (Israel)

The international program closed on October 5 with “Mana”, created by choreographer Noa Wertheim for Israel’s Vertigo Dance Company, at the grand Marjanishvili theater.

Drawing on a line from the Zohar — “What is repaired first, the vessel or the light?” — Wertheim sets out to choreograph the breath itself: the interval between inner and outer worlds.

Her long-developed spiral movement language lends the work the sensation not of staged spectacle but of a living current, at once rooted and ascending.

The dancers — ten in all — move as if following the logic of wind-driven waves: surges, retreats, recombinations. The hour-long performance felt closer to ritual than to display.

A Festival as a Cartography of Questions

The four works, viewed in succession, chart a kind of map of contemporary concerns. Blackstock’s inner heroic quest in a society of stereotypes. Karantzas’s portrait of routine as quiet capitulation. Hermanis’s meditation on the solitude of authority. Wertheim’s search for reconciliation between body and spirit.

Each arrives from a different cultural context and artistic idiom — spoken word and street-derived dance, parabolic domestic theater, filmic psychological portrait, meditative choreographic ritual — yet together they trace the outlines of the twenty-first-century predicament: identity constrained, attention fragmented, institutions in doubt, the body still the primary site of meaning.

Tbilisi, historically a crossroads of empires, languages, and faiths, proved again that a theater festival can be more than a seasonal celebration. It can serve as a civic space where the fractures of contemporary existence are staged with enough clarity to be recognized, if not yet resolved.

By Ivan Nechaev