Binyamin Netanyahu, who won the parliamentary elections at the end of last year, was able to form the new, 37th, government of Israel together with the far-right.

One of the main questions that quickly arose regarding the new government of Israel is whether the country’s policy towards the Russia-Ukraine war is going to change.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the newly formed Israeli government, Eli Cohen, in his inaugural speech on January 2, hinted that Israel will no longer publicly condemn Russia’s actions against Ukraine. He also added that they will formulate a new policy towards the ongoing war in Ukraine, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will present a detailed presentation on the mentioned issue to the Security Cabinet. Even more thought-provoking was Cohen’s choice of name for this policy: In his words, this would be a “responsible” policy in relation to the war.

Shortly after this statement was made (January 3), a telephone conversation was held between Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Eli Cohen. In a statement released by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, it was said the parties discussed the possibility of strengthening trade and economic relations, as well as the situation in the Middle East, North Africa and Ukraine.

All this is happening against the background of the previous Israeli government’s being one of the first to condemn Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. The Israeli and Russian foreign ministers held no talks following Russia’s February 24 invasion. However, it should be noted here that the previous government of Israel did not donate weapons to Ukraine, the reason for which was claimed as national security in regards to Iran. In Israel, there is a fear that their manufactured weapons will end up first in the hands of Russians, and then in the hands of Israel’s existential adversary – Iran, who would then be able to decipher its schemes and be able to would deal a significant blow to the country’s security.

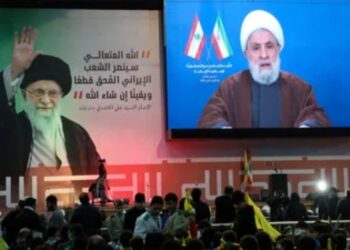

Of no less importance is the fact that, for years, Russia has turned a blind eye to the incursion of Syrian airspace (which is controlled by Russia) by Israeli warplanes, and the intensive bombing of military bases of Iranian and pro-Iranian forces (the Lebanese “Hezbollah”) stationed there.

Naturally, the above led to sharp criticism of the new Israeli government both within this country, as well as in Ukraine and the United States.

Among the critics was Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, one of Israel’s most prominent supporters in Congress, who did not hesitate to say publicly: “I hope Mr. Cohen understands that when he talks to Foreign Minister Lavrov of Russia, he is dealing with a military criminal regime that commits war crimes daily on an industrial scale.”

A special statement on this issue (which, of course, was agreed with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine) was also made by the Ambassador of Ukraine to Israel, Yevgeny Kornichuk, who noted that, according to Kiev, the telephone conversation between Cohen and Lavrov is evidence that Israel’s position regarding the ongoing war in Ukraine has changed.

After such harsh criticism, senior Israeli officials tried to down-play the situation, and told the media that Cohen’s comments were largely related to the previous Israeli government’s public statements and attempts to mediate between Russia and Ukraine, which had failed. They added that the telephone conversation with Lavrov was held based on the latter’s request, and that Cohen informed US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken about it in advance.

In addition, in early January, Israeli media reported that Cohen had tried to have a telephone conversation with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, but the latter was in no hurry to hold talks with his Israeli counterpart. The official reason for the failure to hold the conversation was the New Year holidays.

Another high-ranking Israeli official, who did not wish to disclose his identity, made an additional statement on the issue. In his words, in relation to Ukraine, “there have been no changes in Israeli policy.”

Interestingly, the head of the new Israeli government, Benjamin Netanyahu, has yet to comment on the issue. For months after the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, he avoided criticizing Putin, with whom he has had a very close relationship over the years. But after his party won the parliamentary elections in November, Netanyahu condemned Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, adding that when he took office, he would also discuss the possibility of supplying weapons to Ukraine.

On December 30, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the President of Ukraine, and Netanyahu spoke on the phone. Israel’s main request was for Ukraine not to support the UN General Assembly’s vote on a draft resolution calling on the International Court of Justice to issue a legal opinion on the consequences of Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories. The representative of Ukraine did not attend the vote on this issue (Kiev had voted against Israel in previous votes), thus, according to the Ukrainian side, relations with Netanyahu were given a chance.

During this telephone conversation, the Ukrainian side also raised its own issues. In particular, Kiev requested a transfer of air defense systems from Israel. According to the Ukrainian side, they did not receive a concrete answer on the issue, but did receive a promise that the parties would return to the question in the future. According to the same Ukrainian senior official, neither of the leaders were satisfied with the results of the talks.

In fact, Israel is in a difficult position strategically (as is everyone who tries to maintain any kind of “neutrality” in the Russia-Ukraine war) and the new Israeli government realizes the seriousness of the situation.

If Israel turns to Russia, there is a risk that relations with its main strategic ally, the United States, will cool (and indications of this have already been made in the US). This is unacceptable for its long-term security.

Yet, if Netanyahu’s government moves in support of Ukraine, the Israelis suspect that Russia could transfer technology (including nuclear weapons) to Iran that will directly threaten Israel’s existence. At the same time, there is a danger that Moscow will no longer turn a blind eye to Israel’s actions in Syria. This creates the danger of a military confrontation between Russia and Israel, which is far from convenient for Israel.

That is why the Israeli government is trying to pursue a moderate policy towards both Russia and Ukraine. However, recent events have clearly shown us that the longer and bloodier the Russia-Ukraine war becomes, the more difficult it will be to pursue a balanced policy, and this applies not to the Israeli authorities alone – it, in turn, creates a number of threats and challenges in the field of security.

By Zurab Batiashvili for GFSIS