On August 10, in the thick heat of a Georgian summer, people filed into cinemas across the country to mark what would have been Gia Kancheli’s ninetieth birthday. At Amirani in Tbilisi, before the lights dimmed for Angels of Sorrow, a documentary about the composer, violinist Anastasia Aghladze walked onstage and, with an almost conspiratorial stillness, raised her bow. What followed was the sort of playing that makes an audience forget to shift in its seats: long, transparent tones, the pauses as important as the sound itself, a performance pitched somewhere between an invocation and an autopsy of memory.

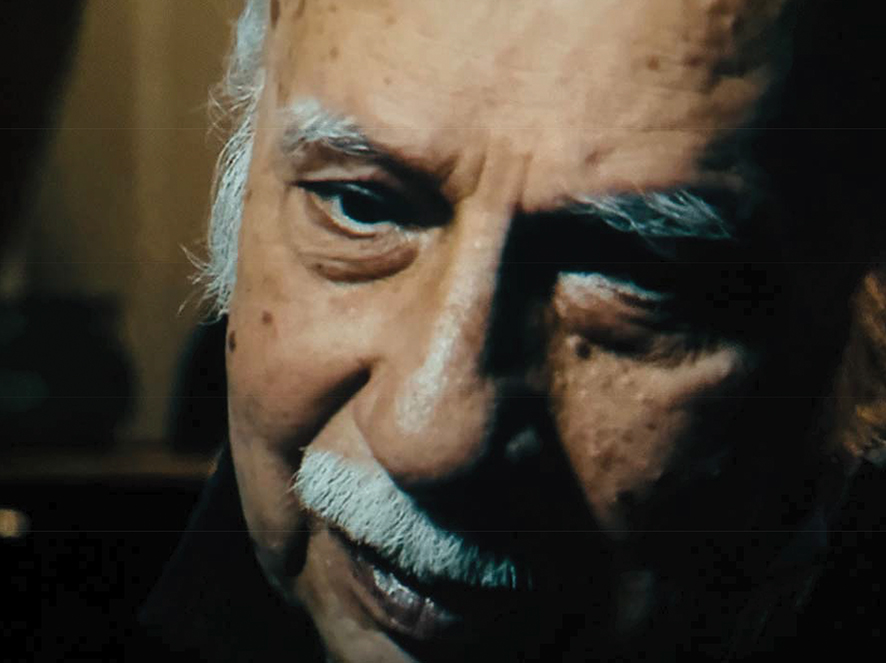

The film, directed by Teo Jorbenadze and originally made for Kancheli’s eightieth, refuses the usual cradle-to-grave hagiography. Instead, it drifts alongside the composer during a tour of Berlin, Brussels, Antwerp, Baku, and Tbilisi. There are no staged revelations or climactic reconciliations—only the slow accumulation of moments: the curve of a conductor’s hand, a snatch of backstage banter, John Malkovich reading aloud a particularly vicious review with the air of someone savoring an obscure wine. Kancheli appears not as a marble bust, but as a man aware that a life’s work can be both monumental and provisional, subject to revision even in its final bars.

The tour isn’t filmed as a victory lap. It’s more like a moving workshop in survival. We watch Kancheli slip between languages and climates, bowing to applause that is warm but never quite the same from one city to the next. Backstage, there’s the quiet rustle of sheet music, the clink of a cup set down, the silent communions with fellow musicians—some of them old friends, some new conspirators in this rolling act of defiance.

With Kancheli, the end of the piece is never the end. The silence that follows is part of the score

For Kancheli, freedom was never a slogan—it was the working condition without which music could not exist. In the Soviet Union, this insistence was enough to make him suspect. Party critics accused him of writing music like a drug: slow, intoxicating, “pleasing to enemies in capitalist countries.” It was meant as a condemnation, but the truth is, the charge was accurate. His compositions did offer something addictive: a pacing so deliberate it felt subversive, a refusal to hurry toward resolution, an orchestral palette that could slip from lullaby to detonation in a single movement.

The film makes clear that these accusations didn’t silence him—they sharpened him. He answered not with speeches, but from the stage. A crash of brass where they expected a march. A minute-long silence where they expected fanfare. A sudden swell of strings that felt less like patriotism than a warning. Watching the Berlin audience lean forward in their seats, or the Tbilisi crowd close their eyes mid-phrase, you sense that Kancheli’s true language was not Georgian or Russian or English, but the shared grammar of pause and release.

Before the screening, Aghladze’s playing acted as a preface. She approached Kancheli’s score as if it were an unstable document, a text to be read aloud in the knowledge that the ink was still drying. Her bow lingered at the edge of each phrase; her vibrato barely disturbed the line. At one point she held a note so delicately that you could hear the air-conditioning sigh above the audience. This was not the sort of virtuosity that courts applause—it was a kind of tact, the musical equivalent of leaving a sentence unfinished so the listener can supply the ending.

Sociologists of ritual might say that Kancheli’s concerts—like the one captured in Angels of Sorrow—function as communal acts of mourning disguised as cultural events. They are places where private grief becomes shareable, where silence is not awkward but binding. Anthropologists might go further and point out the resemblance to traditional Georgian laments, the kind sung at funerals in mountain villages: a single voice bending around the note, stretching it into a space big enough to hold loss without breaking.

The documentary makes you aware of how rare this is now. In the twenty-first century, speed is the reigning aesthetic; art is praised for its immediacy, its “impact.” Kancheli’s work resists that economy entirely. Byung-Chul Han calls it the “time of the tired self”—an era when our inability to dwell in slowness erodes our inner life. Kancheli composed against that erosion. His music insists on the value of duration, of staying in the wound long enough to learn its shape.

When the credits rolled at Amirani, the audience didn’t move. The lights were already up, the hum of the projector replaced by the mechanical breath of the ventilation system, and still they sat there. Perhaps they were reluctant to shatter the mood. Or perhaps they understood something essential about Kancheli: that the end of the piece is never the end. The silence that follows is part of the score.

By Ivan Nechaev