The term “dollarization,” commonly used among academic economists and finance specialists, has already entered Georgians’ everyday vocabulary. Few people, however, understand what dollarization is, how it comes about, and why they should care. Below, we try to fill this gap, explaining some basic concepts and discussing why and how dollarization affects ordinary people’s lives.

What is dollarization, exactly?

The term dollarization officially refers to the legal substitution of domestic currency by a foreign currency (De Nicolo et al., 2003). Examples include Zimbabwe, a country that struggled with rampant inflation before legalizing the use of the US dollar alongside the domestic currency in 2009, and then, six years later, completely suspending the use of domestic currency. Unofficially, however, the term dollarization is used to denote the usage of foreign currency that is not legal tender alongside the domestic currency (Yeyati, 2006). This typically means that while the use of foreign currency is prohibited in official transactions, foreign currency is still used very commonly, for example, to index certain types of transactions (like selling or renting real estate in Georgia), or to store value (e.g., saving money in USD or Euros instead of Georgian Lari).

How can we measure the extent of dollarization, and how dollarized is the Georgian economy?

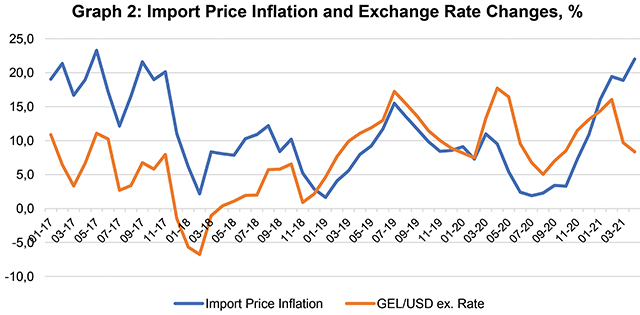

There is not one single way to measure the extent of dollarization. For example, we can never know exactly the share of renters in Tbilisi that pay their rent in USD or USD equivalent (although one can guess that the percentage is quite high). But there are some proxy measures, i.e., easily observable indicators, which can tell us about the general trend in dollarization. One such measure is the share of bank deposits denominated in foreign currency. This indicator directly shows which currency people prefer for their savings, and, indirectly, to what extent people are tied to the use of foreign currency in various financial transactions. In Georgia, the process of bank deposits being dollarized has been slowing down recently.

However, dollarization levels have been well above 50% for the last 20 years (Graph 1).

This is not just a problem for Georgia. Dollarization of bank deposits (also known as asset dollarization) tends to be a particularly stubborn problem affecting many emerging economies. In this group, Georgia stands among the highly-dollarized cohort.

Why is dollarization so persistent in emerging economies?

As one can see from the graph, in 2002-2004, deposit dollarization hovered around 85%; at the end of 2020, the deposit dollarization ratio was 62.75%—much lower but still quite high. Financial dollarization is so stubbornly persistent precisely because it is not a black and white phenomenon. Like many things in life, it has both positive and negative sides. First, let’s discuss the possible benefits offered by dollarization.

1. Some argue that the biggest advantage of financial dollarization is the hedging of exchange rate risk for commercial transactions. Imagine a Georgian firm that has foreign partners who have to be paid in dollars. Would it not be more natural to keep dollar deposits to make the transaction process easier? That would also eliminate exchange rate risk (imagine having to pay more in terms of GEL because of an unexpected jump in the exchange rate. That would not be an issue if the transactions were made using dollar deposits). It should be emphasized, however, that if the payments need to be made in Euros or other non-USD currency, dollarization won’t provide the benefits mentioned above. This counterargument is valid for Georgia too, which has trade relations mostly with Turkey and the Eurozone.

2. Financing transactions that are de-facto dollarized (e.g., real estate purchases). Because in emerging economies, including Georgia, many construction companies rely on foreign investors for financing, and payments of dividends may be tied to the dollar, it is more convenient to express prices in dollar terms. Moreover, since some materials have to be imported, just as in the previous case, it is easier to keep dollar deposits to make dollar payments.

3. Another reason is obvious to anyone who remembers life in the region in the 1990s: clearly, asset dollarization guarded against high inflation and protected savings from the erosion of value. The roots of the dollarization problem in Georgia in particular can be traced to the unstable political and economic environment after the fall of the Soviet Union. The accelerating inflation and volatile political setting during the transition to a market economy eroded confidence in the national currency. Underdeveloped financial markets and dependency on money transfers from abroad nourished dollarization in the Georgian economy.

4. People/businesses may also keep their liquid assets in foreign currencies due to other considerations:

a) The procyclical nature of exchange rate risk in emerging market economies: during periods of recession or low growth, emerging economies typically observe devaluation of their currency against the US dollar (Cordella & Gupta, 2014). If a Georgian business has a loan denominated in USD, then during a recession they will face a double burden: devaluation increases the GEL value of their debt, even as their GEL revenues decline. Hence, a business may choose to keep part of their deposits in USD to protect themselves during a recession. During times of strong economic growth, the opposite may happen: dollar deposits may lose their value due to appreciation of the GEL. This effect, however, is dampened as the negative impact is less noticeable because of the growing economy.

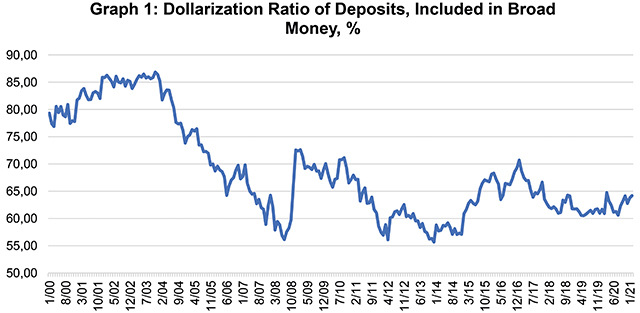

b) Devaluation could translate into price increases for imported goods. We do see evidence of the correlation between import price inflation rates and GEL/USD exchange rate changes in Georgia (graph 2). Hence, for people and businesses who rely heavily on imported goods for consumption/production, keeping savings/assets in USD provides a hedge against import price increases.

5. Finally, the high volatility of the exchange rate may in itself contribute to a high level of dollarization in the economy, as people become increasingly uncertain about the value of the domestic currency.

What are the drawbacks of dollarization?

The high level of dollarization is a serious challenge for the country. There are a number of reasons why dollarization may hurt the economy, but those immediately obvious to a non-expert are the following: if the economy is highly dollarized, the risks in the banking system rise; the real economy becomes more unstable and exchange rates become more volatile. Imagine having liabilities in USD and income in GEL.

Hence, if you expect the GEL to depreciate, you are likely to start buying dollars. When a lot of people behave this way, the demand for GEL decreases and it loses value, depreciates against the dollar, as anticipated. The most interesting part of this mechanism is that the expectations might have arisen without any logical explanation, bringing real changes to the economy and increasing its volatility. The increased volatility of the exchange rate then feeds into the process of dollarization, creating a vicious cycle that prevents dollarization levels from falling and giving rise to a so-called “dollarization hysteresis” (a phenomenon that is responsible for persistence of dollarization even as the exchange rates stabilize).

That could affect the debt burden and the profitability of such firms.

If the Larization policy works well, the exchange rate should become less volatile in the long run and will in turn reduce the need for dollarization

The expectations mechanism is further augmented by the common nature of currency mismatch in Georgia, meaning that many citizens’ assets and liabilities are expressed in different currencies. It has already been mentioned that a significant part of Georgian citizens’ debt is denominated in USD, because of the lower interest rate offerings by domestic banks on loans in USD. Consequently, the balance sheet of such debtors is prone to exchange rate risk, because their source of income is in a currency different from USD. These debtors might be particularly responsive to expected changes in the exchange rate, buying dollars when they expect the GEL to depreciate or buying GEL when they expect the GEL to appreciate. These transactions will bring forward changes in the exchange rate, which might be based solely on these expectations and the actions from debtors in response to expected changes in the exchange rate.

What can be done to reduce dollarization?

As we saw, while asset dollarization can make sense to individual market actors, it poses significant risks for a country and financial system as a whole. Reducing dollarization has been high on the Georgian government’s agenda. In 2016, the National Bank of Georgia (NBG), together with the Georgian government, adopted a 10-point Larization plan. As part of the Larization policy, loans of less than 100,000 GEL could only be issued in local currency. Since 2019, the threshold has moved to 200,000 GEL.

It has also become compulsory to denote real estate prices in GEL. Moreover, the government offers subsidies to induce citizens to de-dollarize their loans. However, despite the Larization policies currently in place, the dollarization level of deposits still remains high in Georgia (the 2020 average rate was 66.36% (NBG)). Clearly, people who keep their deposits in USD are not irrational. For the reasons already discussed above, if the overall dollarization level in the economy is high, it can make more sense for individuals to keep their assets in dollars as well. Given that bringing down the average dollarization level in the economy is not an easy task (it takes time), we can expect that the asset dollarization problem in Georgia will persist for some time.

Is it possible that dollarization will decrease in Georgia in the long run?

In the long run, we can look forward to lower dollarization levels if certain conditions are met. To name a few:

a) When businesses have access to and are able to use various financial instruments to hedge against foreign exchange risk (rather than just storing their deposits in USD which, as we saw, is an imperfect hedging instrument in the Georgian context)

b) When all sectors of the economy become gradually and fully de-dollarized (e.g., the real estate sector).

c) To the extent that the Larization policy works well, the exchange rate should become less volatile in the long run and will in turn reduce the need for dollarization.

By Archil Chapichadze, Yaroslava Babych