Georgia is filled with ancient historical places, so much that it is difficult for many visitors to truly see everything. It encompasses such a wide variety of terrain and climate zones. One can go from swimming on a beach surrounded by palm trees to skiing in immense snow-covered mountain ranges, only to be followed by dining at a caravanserai in an arid valley. With this broad buffet of options, many find themselves spending much of their time in transportation across the country.

For a more local delight just outside the capital, there lies a curiosity steeped in the socio-cultural and religious history of the region. The monastic complex built into the side of a mountain is an awe-inspiring experience, even for the casual visitor. As it still maintains relative popularity in the litany of places to see, travel and touring the complex is easier than some other more hidden gems.

Travel to the complex, as with many of the sights across the country, is easy. Via the infamous marshrutka minivans, arrangements are inexpensive, though require a certain level of sacrifice of comfort. The journey typically ranges between one to two hours depending on the confidence of the driver.

The view along the way is incredibly impressive. Rolling brown and green hills that have clearly been windswept for a millennia cover the vast expanse of virtually uninhabited land. Much of the exposed rock on the windward side of these hills has beautiful variations in the rock colors. The jagged streaks of this rock gives it the impression of having being painted by a colossal brush.

Only the occasional herder, with his accompanying livestock of choice, traverses the area. A large salt-lake, and the occasional small pool of isolated water provide a rare alternative to the wild and almost treeless grassland.

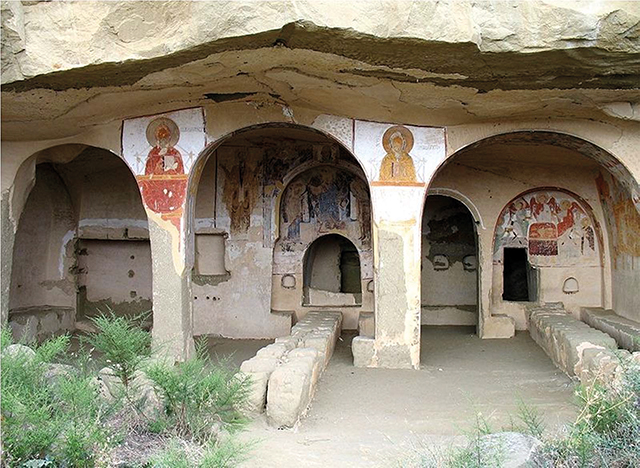

Arriving at the complex, there are usually tour guides willing to translate and help with the experience. Despite this, there are opportunities to explore most of the complex unaccompanied. There are however some areas restricted to visitors, as the monks who care for the complex do indeed live on the site. The small chapels and hovels hewn into the rock of Mount Gareji are adorned with ancient Christian symbols.

The history behind the complex goes back farther than even some of the oldest locations on tourist’s visit list. Constructed in the 6th century AD, Assyrian monks traveled to reinforce the expansion of a growing Christian movement in the region. St. David Garejeli, the leader of the thirteen monks that founded the complex, oversaw its expansion. More, smaller chapels were built on the mountainside.

At the height of medieval Georgia, the complex was the site of an accompanying village and agricultural lands. Many of the Georgian royalty made pilgrimages to the site, with one king even choosing it as his residence following his abdication from the throne. Davit Gareji survived many of the wars and violence that racked the region, including the Mongolian and Persian invasions. Despite damage to the complex and the killings of many of the clergy, it was continually rebuilt and preserved.

With the Bolshevik invasion of the country in 1921, the monastery was forced to close. The negative Soviet opinions toward religion left the complex unattended and virtually abandoned.

Given the area’s arid climate and vaguely perceived similarity to the terrain experienced by Soviet forces in Afghanistan, it was used as a training area. The monastery was further damaged during these exercises, though, after much protest at the site and in the capital, the area was vacated by military forces. Upon the collapse of the Soviet Union and restoration of Georgian sovereignty, the monastery complex was restored and re-inhabited by the monks.

The complex today is still a minor point of contention between Georgia and Azerbaijan. As a number of the buildings fall along the shared border, there have been several terse statements made between Azerbaijani and Georgian government officials. Despite this, the monks see this as post-Soviet undermining of the relationship between Christian Georgians and Muslim Azerbaijanis.

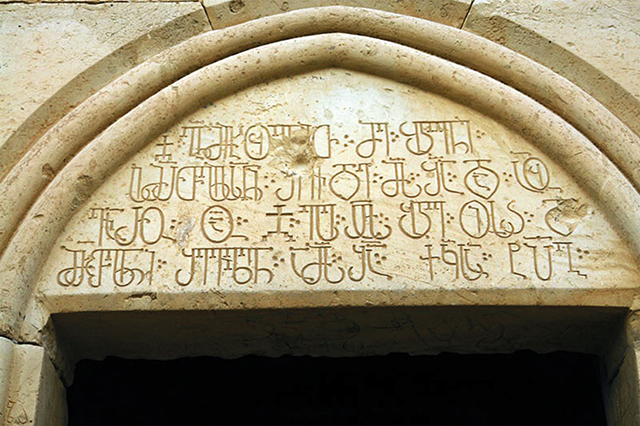

While the Georgian side has long claimed this has always been their territory, the Azerbaijani authorities propose another viewpoint. To them, the area is historically home to supposed “Caucasian Albanians,” who are only some of the ancient inhabitants of what is now Azerbaijan. However, much of this history is disputed by many scholars. This is due to the numerous Georgian artworks and markings that cover the complex’s structures and walls.

Despite this disagreement, the majority of the conversations regarding the complex today are agreeable. Both sides have border security positions near the complex, but little heed is paid to them as the beauty of the preserved interior frescos and ancient caveworks pull visitors’ attention away. The complex is complete with its own dining area, irrigation system, and additional housing areas in the surrounding hillsides.

Upon preparation for leaving the complex, the church operates a small shop of ecclesiastical goods, religious icons, and even some wine made by the monks. Returning from the area is a reverse of the incredible landscapes seen on the initial journey. For the traveler feeling fortuitously famished, the aforementioned town of Udabno has a selection of small family restaurants and guest houses.

The total experience can be only a day, or even a few with a short stay in the quaint and comfortable Udabno. It is one that should not be missed, and can easily fit into any travel itinerary. As an unassuming but important piece of Georgian history and culture, it can satiate and impress even the most experienced globetrotter.

By Michael Godwin