There are productions that happen on stage and there are productions that happen in a city. Mud, the new play by Davit Khorbaladze directed by Mikheil Charkviani, belongs decisively to the second category.

Its action unfolds in a metal container, parked in the courtyard of a crumbling Soviet-era housing block on the outskirts of Tbilisi, where Open Space—Georgia’s most restless experimental theater initiative—has made its home. The location is no neutral choice. By leaving the center, by staging itself in a ruin, Open Space declares that contemporary Georgian theater is not only about repertoires and premieres; it is about reclaiming the right to make art in spaces that the city, and perhaps the state, would prefer to abandon.

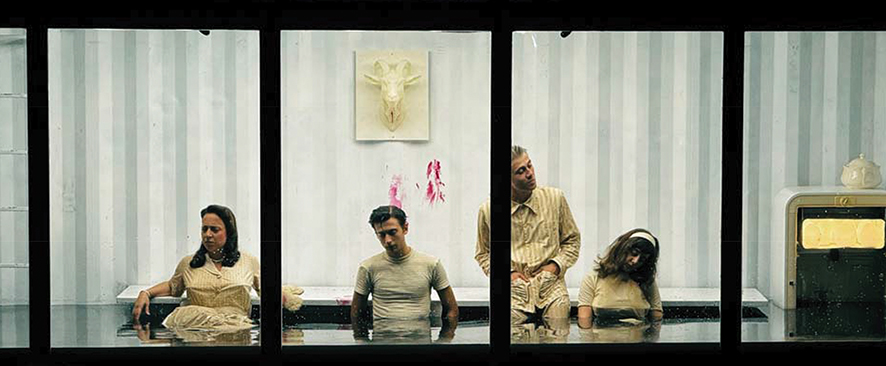

The first image sears itself into memory: a pristine white domestic interior assembled inside the shipping container. The family—mother, father, son, daughter—look like they have stepped out of a detergent commercial. The floor, the furniture, even the cutlets on the breakfast table gleam with a sterile brightness. It is a visual joke as sharp as it is chilling: a family cocooned in impossible cleanliness, boxed off from the decay that surrounds them. Behind them, the façade of the ruined panel building looms like a mausoleum of history. This juxtaposition—clinical container versus rotting architecture—anchors the production in the contradictory aesthetics of Tbilisi today: glossy renovation projects pressed up against zones of abandonment, whitewashed rhetoric pasted over systemic collapse.

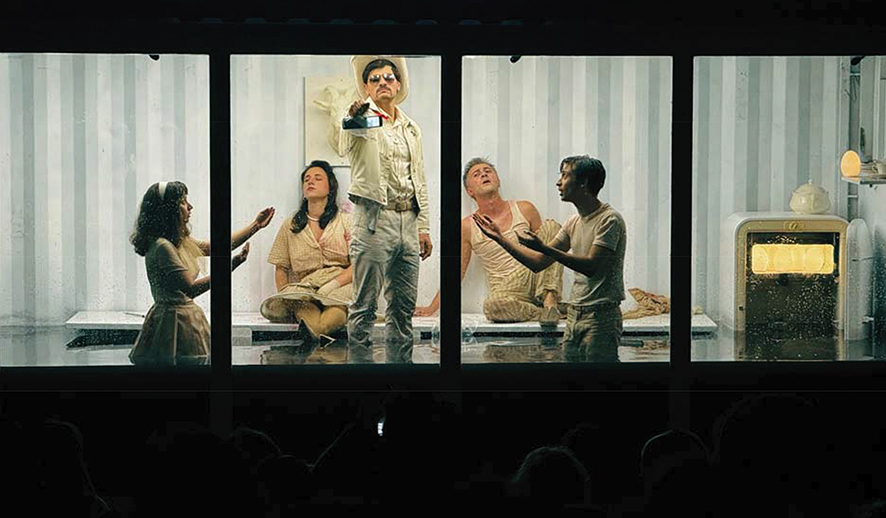

The play’s mechanics intensify this contradiction. The actors are sealed inside their immaculate box, as if inside an aquarium. They cannot project to the audience in the courtyard. There is no live voice. Instead, each spectator receives a pair of headphones. Through these, the dialogue is transmitted with studio clarity, while sub-bass vibrations ripple through the ground, puncturing the body from below. This sound design (a collaboration between composer Erekle Getsadze and the technical team) produces an uncanny duality: the intimacy of whispered speech in your ear, the violence of vibration in your chest. Theatrical presence is displaced into a mediated acoustic experience. You watch bodies behind glass, but you hear them inside your skull.

This mediation is not a gimmick—it is the play’s central metaphor. The family is trapped in denial, endlessly insisting that “nothing has happened” despite evidence to the contrary. The audience, meanwhile, is forced into a parallel condition: to witness but never touch, to hear but never speak back. It is theater as surveillance, as voyeurism, as forced distance. The actors, for their part, play inside the box like animals in a terrarium. Their gestures become heightened, stylized by the container’s claustrophobic frame. They are both protected and endangered, immaculate and drowning.

Drowning becomes literal. As the play advances, muddy water begins to seep into the pristine space. First a trickle, then a flood. The family continues to deny, continues to cook, to set the table, to arrange their breakfast as if nothing were happening. But the water rises until their movements are slowed, distorted, their white clothes stained and heavy. The sterile idyll collapses into slosh and struggle. The metaphor needs no explanation: denial is not sustainable, cleanliness cannot last, the swamp rises everywhere. And yet the insistence on routine persists. The father still polishes an egg, the mother still tends to the cutlets. Survival, in this context, means performance of normality.

The socio-political resonances of this staging are inescapable. By situating the play in the shell of a decayed panel building, Charkviani connects private denial to collective amnesia. Post-Soviet Tbilisi is full of such ruins—monuments of deferred collapse, inhabited by ghosts of history. To install inside such a ruin a hermetically white family home is to stage the very contradiction of Georgia’s public life: official narratives of cleanliness and progress sealed off from the muddy realities of corruption, repression, and decay. The dedication of the performance to persecuted and exiled artists makes this resonance sharper. Denial, here, is not an abstract condition; it is a daily political practice. The ostrich farm, with its giant eggs and buried heads, is less rural comedy than allegory of a society encouraged to look away.

What is remarkable is how the performance reconfigures the spectator’s role. Theater usually traffics in presence, in the unmediated vibration of voice in air. Here, presence is engineered technologically: headphones, sub-bass, container walls. The effect is paradoxical. On the one hand, the audience is hyper-connected—every breath of the actors courses directly into the ear canal. On the other hand, the audience is radically alienated—separated by steel, glass, and mud. This double condition mirrors life under regimes of control, where citizens are overwhelmed with mediated information while simultaneously cut off from real political agency.

In aesthetic terms, the production participates in a lineage of container-theater and architectural interventions familiar in European performance art—from Christoph Schlingensief’s Container Aktion projects to the boxed installations of Rimini Protokoll. But in Tbilisi, the gesture takes on a different charge. It is less about international formal experimentation than about local survival. To place a play in a shipping container in the courtyard of a ruin is to acknowledge that Georgian theater’s future may be nomadic, provisional, improvisational—always one step ahead of erasure.

The actors—Keti Javakhishvili, Kato Kalatozishvili, Kakha Kintsurashvili, Tornike Lazashvili, and Temo Vacharadze—deserve mention for navigating this extraordinary apparatus. Performing inside a soundproofed, water-filled container demands a new physical language. Gestures must be both precise and exaggerated to be legible through glass; voices must sustain emotional truth for microphones without the feedback of live audience energy. Their acting oscillates between the stylized pantomime of silent cinema and the forensic intimacy of radio drama. This doubleness is exhausting to sustain, yet it is exactly the doubleness the play requires.

By the final scene, when the container is a swamp and the family still clings to their rituals, the production achieves a devastating clarity. The mud is no longer metaphor; it is matter. Denial, however radical, cannot keep shoes dry. And yet the denial continues. This is where the political bite of the piece lands: repression thrives precisely because people manage to perform normality while waist-deep in catastrophe.

Mud leaves the audience with more than images. It leaves a sensation: the weight of bass in the chest, the claustrophobic sound of headphones, the visual dissonance of sterile white against rotting concrete. It stages denial as a physiological condition. And it reaffirms what Open Space has been insisting for years—that theater in Georgia is inseparable from the city’s fractures, its ruins, its displacements.

To watch Mud is to realize that the family’s container is not sealed. The water that floods it is the same water that seeps through Georgian society, through its institutions, through its cultural life. To watch Mud is to admit that the mud is already here.

Review by Ivan Nechaev