Radio Free Europe/RL’s Georgian Service sat down with Chatham House’s Samantha De Bendern to talk about two big elections, starting with the UK elections, the less controversial of the two. De Bendern, a British consultant based in southern France, has a diverse background in political risk and finance. Initially focused on Russia and Eastern Europe within security and international relations roles at the European Commission, NATO HQ, and Control Risks Group, she later transitioned to banking, until 2018, when she turned fully to political risk consulting and writing. She continues to be involved in EU affairs and actively combats disinformation in France.

With “Labour” winning a record number of seats in the UK’s parliament, just how deep was the hole that the Tories (Conservatives) had been digging themselves into over the years?

The first thing we really have to bear in mind is that, yes, this was a Labour victory, but we also have Nigel Farage’s Reform Party that got just over 13% of the votes. Because of the way the British electoral system works, it only really represents very few voters, and the proportional system is such that they have a disproportionate amount of seats. But yes, the Tories dug a terrible hole for themselves, largely because Brexit has been a disaster for the United Kingdom.

Brexit promised many things: First of all, the whole ethos behind the Brexit vote was to curb immigration from European countries. The Leave campaign was a very clever campaign, using manipulation, using very up-to-date technology to penetrate social media. There was also, again, ample evidence of Russian financing behind the Brexit campaign, and it was very brilliantly done. One of the architects of that campaign, Dominic Cummings, who ended up being advisor to Boris Johnson, said: “We used emotions like snake oil; they [Stay] used facts and figures.” The reality is that nobody cares about the facts and figures; they only want emotion. The people didn’t have a clue what they really wanted; they just wanted to get rid of immigration and get rid of the Brussels bureaucracy, not realizing that you can’t get rid of the Brussels bureaucracy, because even if you’re outside the European Union, if you want to trade with the European Union, you have to deal with it.

The Tory government was unable to curb immigration. Today, illegal immigration is at an all-time high in the UK, worse than ever before. And the British can no longer send illegal immigrants back to Europe because they’ve left the European Union and the Dublin Agreement, which allowed them to send migrants back, so that’s why they came up with this crazy scheme to send them to Rwanda.

The bureaucracy that they promised to slash got worse overnight, particularly for small companies. So none of the promises they made were able to be fulfilled. Then they were hit with the pandemic, which undoubtedly played its own role. Then there were disasters related to the way the pandemic was managed, corruption in protective physical equipment procurement, the scandals surrounding Boris Johnson and the Partygate, so it was just disaster after disaster, and they began to be hated in the country.

How big a job does Keir Starmer have when it comes to “Making Britain Serious Again”? Where does one begin with that?

He’s appointed a very sensible cabinet. He’s now going to focus on having good relations with the European Union and, of course, the United States. And I think he will be more driven by pragmatism than ideology. But it’s a big job, because the whole world is a mess right now.

That pragmatism rather than idealism mantra, what does that translate into when it comes to the war in Ukraine? Will we see any significant shifts?

From the UK point of view, I don’t think we’ll see any dramatic shifts. One thing that is a striking feature of the United Kingdom is that the whole political establishment, with the exception of a few fringe actors like Nigel Farage, has exactly the same view on what needs to be done with Ukraine, and that is to support Ukraine in its fight against Russia. They understand that European security is UK security. This is a very different situation compared to France; in the UK, the war in Ukraine was not really an issue of debate or an issue of contention.

Keir Starmer was very clear about wanting to support Ukraine. Our new defense minister is already in Ukraine, and he has only been in office a few days! So, in terms of where Ukraine is concerned, the UK election is a non-event: The support will continue at the rate it is, maybe even potentially increasing if the budget allows.

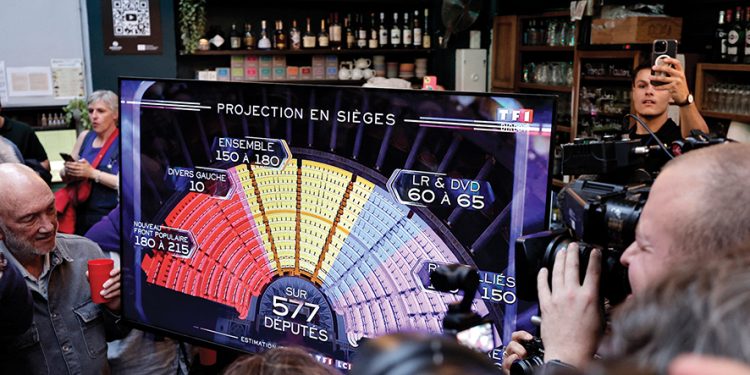

Now on to the French elections. How did Macron’s gamble in calling snap elections work when it came to not giving National Rally a victory?

First of all, I think it’s important to understand what Macron’s goals may have been, because it is a big mystery to many people. He could have had two potential goals. I don’t think he envisaged what actually happened. I think one option he had in mind was his party coming out reinforced and allowing him to govern without having to constantly fight the parliament, and the other was that National Rally would win, make a mess of things, be shown to be completely incompetent, and then we would be able to get rid of the shadow that has been hanging over French politics since 2002, the shadow of the far right government.

But what happened is something that nobody was expecting: As soon as he announced the elections, the Left came together. This was very unexpected, because the Left is a very divided coalition, particularly on foreign policy issues. You have Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who thinks Hamas are wonderful, who probably thinks Putin is wonderful as well. He’s a former Trotskyist. And on the same spectrum, you have Rafael Glucksmann, a former advisor to Saakashvili, who is absolutely crystal clear as to where the threat to Europe lies, and that is Putin. He’s also absolutely crystal clear that supporting Ukraine is a number one priority and, of course, he’s more of a left social democrat than the crazy left.

It seemed unbelievable that these alliances would come together. But they did, coming together as a left force united by two things: Their dislike of Macron and their absolute hatred of National Rally. So in the first round, where National Rally came in first, that’s when the big questions began to be asked in French society: What do we do if there’s a runoff in my constituency between National Rally and whoever else, particularly Unsubmissive France? And the new National Front, were very clear the day after the first round, they said, “we will withdraw our candidates where we believe that the Macron candidate has a better chance of winning.” They were absolutely unambiguous in this. And the French population saw this as a sign that they are genuine in their belief that National Rally was a threat to democracy.

The Macron party, in the aftermath of the first round, were a little bit more on the fence. They said, “we will withdraw our candidates if we feel that the remaining candidates are not a threat to democracy.” In the end, what happened is that the Macron party also withdrew, even if they felt that a far-left candidate had a better chance of winning the election.

This left coalition that was so unlikely to come together, how likely are they to remain together?

That’s the question on everyone’s lips. With the threat of National Rally being diminished, all the in-fighting between the left and the Macron party can start again. And one of the things that the left coalition often said amongst themselves was that, “okay, we hate each other, but we’ll fight after the election.” So now we’re going into completely unknown territory. France has a big hangover; a hangover in the sense that many people were celebrating the election results, but also it’s like, “okay, what are we going to do now?”

What will they do in regards to the foreign policy, especially with Mélenchon being the guy he is?

Mélenchon’s party does not even have a majority in the left coalition. They are the party with the most votes, but if you then look at the breakdown of the other parties in the left coalition, he does not have the majority. And while the president does have the lead on foreign and on defense policy, the prime minister and the government will hold the purse strings; they’re the ones who will control military spending. With that in mind, one can imagine that military spending for Ukraine could be one of the bargaining chips that will be used by the government to say, “okay, give me the money for Ukraine, and I will do something about retirement or do something about the minimum wage or the environment or something.”

Could it be used the other way round? Making concessions at the expense of Ukraine support?

It could go either way. But, as I said, one of the strongest pro-Ukraine voices in France today is in the Socialist Party. Inside the Left Party there are some extremely strong pre-Ukrainian voices, which will put pressure on the other people in the left. So, it’s not an ideal situation, and things were better before, but it’s not the disaster it could have been.

Back to Macron’s gamble – how battered is he emerging out of this scuffle? And what does it do, among other things, to his dreams of being the leader of “United Europe”?

I think it’s damaged him a lot, because he is much weaker now at home. He’s gone through this very humiliating process, both European elections and the two rounds of the parliamentary elections. He’s been very absent. The fact that the pro-Macron party had to campaign without using Macron because he’s so unpopular, shows how disliked he is. And he’s definitely lost his authority on the international stage.

One thing about Macron is that he’s very bad at building alliances. He’s bad at building alliances at home with his political peers, even within his own party. He’s bad at building international alliances. He says things without consulting his partners. So when he said, “I don’t exclude sending troops to Ukraine,” personally, I thought it was a great thing to say. A lot of France’s partners thought it was a great thing to say. But you don’t say things like that without consulting anyone, without warning at least your partners. And he does the same thing internally. He announced the snap elections without even properly informing his prime minister, and the prime minister had to do all the hard work. He’s not only a maverick, he’s a bit of a despot. You know, I like his policies and I’m a strong Macron supporter, but I think he’d like to just be able to be a mini dictator, a benign, friendly, well-intentioned dictator.

Not to delve into armchair psychology, but would that explain his attempts to strike some sort of relationship with Putin?

He wants to be the new head of Europe and the new architect of European security, and this was evident well before the war in Ukraine, but is even more so now. He saw himself as the one who was going to be the bridge between Russia and the Western world, and this is a very, very French thing, this sort of very romantic notion of Russia, things like because Tolstoy wrote parts of ‘War and Peace’ in France, that means Russia is France, and they seem to forget that we had Russian troops here after the Napoleonic Wars. And there’s this sort of obsession with Russia in France which also played a part in Macron’s refusal to see the truth of who Putin is.

What do you think the straw was that broke the camel’s back? When did he see the light?

I think it was a series of things. First of all, Putin saying one thing to him on the phone and then doing something else. And then their uncovering up all the evidence of the war crimes, Bucha, Mariupol and so on. And so, slowly, Macron began to realize that Putin was lying to him and that Russia was lying about what it was doing in Ukraine. And not to award too much importance to the role that my own TV station played, but I work for a French television channel called La Chaine Air 4, and we had 24-7 coverage of the war in Ukraine for two and a half years. We stopped in June this year when the election period started. I was on television four or five times a week doing two- to three-hour shows non-stop on the wall, and our show became one of the most popular TV shows in France. What we were told is that the president and the cabinet watched us, because we were showing footage from all the various telegram channels, a lot of footage from Radio Free Europe, going into a lot of detail as to what’s been happening. And they also realized that the French public was interested; it resonated with them.

Let’s talk about his chief rival domestically – Marine Le Pen who, at first glance, seems to be the big loser in this situation. Is that so?

I don’t think we can call this a defeat for National Rally: They have more than doubled their MPs, and have 143 members of parliament. That is enormous. This whole month of hysteria in France was because of them. They definitely didn’t get everything they wanted, but the fact that between 10 and 11 million French people voted for National Rally means something.

National Rally has its roots in Vichy’s France, and one of the founders is Jean-Marie Le Pen, and the second founder was a former French SS. These are real Nazis. And much more importantly, for those who read and listen to Radio Free Europe, are the links with Moscow. There’s the well-documented 9 million euro loan from the Russian-Czech Bank in 2014, after the annexation of Crimea. Then you have the fact that for the five-year anniversary of the annexation of Crimea, certain members of National Rally went to Crimea to celebrate with Putin. You have the fact that some of the people who were on the ballot sheet observed Putin’s re-election in 2018. People, staffers and members from National Rally, were in DNR and LNR during the referendum. This is a party that has very, very tight links with Moscow.

How much do you think Le Pen’s pro-Russian rhetoric was actually a factor in the elections?

I think it damaged her. But the very thing that people are saying- that her getting third place instead of first place is a defeat, is already a testament to her success, because that would have been unthinkable a couple of years ago.

Interview by Vazha Tavberidze