The Center of Contemporary Art (CCA) is determined to engage citizens with environmental issues in Georgia through workshops, exhibitions, presentations, and ‘an informal master’s degree.’

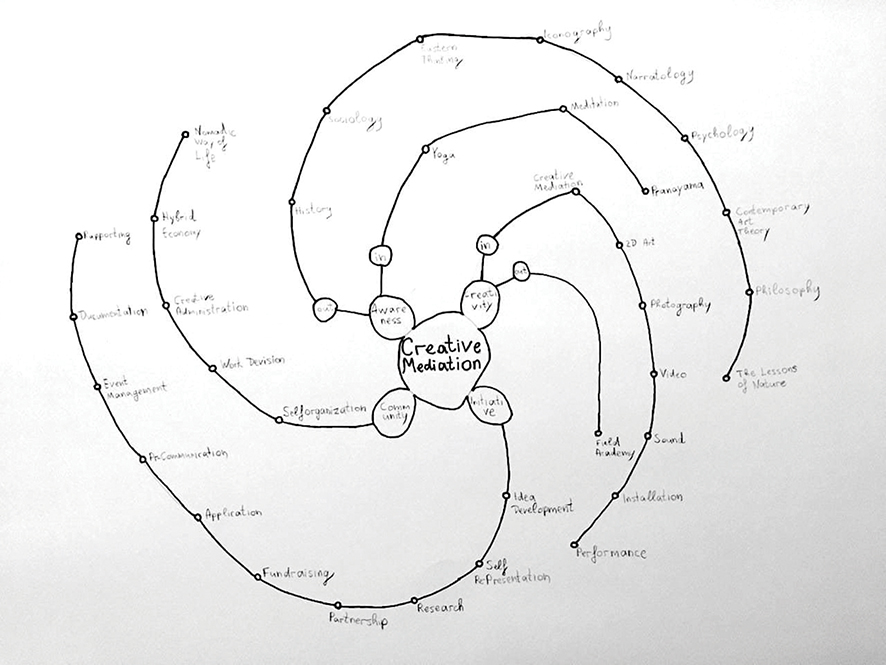

Established in 2010, CCA was founded by Wato Tsereteli, an artist who studied film in Georgia and photography in Belgium. He returned to Georgia in 1999 to create educational platforms supplemented by other creative outlets, such as workshops, residencies, exhibitions, and more. To bring this idea to life, he launched ‘Creative Mediation,’ an informal master’s program for those interested in actively working on social and ecological projects.

The master’s program, which has been ongoing for at least ten years, recently started its new cycle. As part of the introduction week, a three-day event was held for the public at the Goethe Institute in Tbilisi. Tsereteli says the event’s focus, ‘From Me to We,’ was to engage listeners about the current climate issues and to address the low understanding regarding this topic in Georgia.

“We are proud of our nature, but we are not aware [of the climate]. Generally, Georgia is like a book that has yet to be read,” says Tsereteli. “Its totalitarian past had a totalitarian interpretation of landscape and everything. But when it collapsed, there was no new interpretation. We have all kinds of values, but we don’t see them, and we don’t take care of them.”

The event took place from September 17-19 and involved more than ten Georgian and international speakers who gave talks. Topics ranged from raising awareness about professions, disciplines, and issues within ecology.

Tsereteli tells GEORGIA TODAY they invited international guests from Denmark after CCA representatives visited the country this past summer and were amazed by the high-quality involvement and participation of volunteers in Georgian society.

According to Tsereteli, “something so lost and damaged in [Georgia] is on the highest level there.”

Simon Dalsgaard is the head program coordinator of the Danish Cultural Institute in the South Caucasus. He gave a lecture at the event on a Danish case study about self-organization and the volunteer culture throughout the country. He said more than 90% of the country are members of one or more volunteer-based organizations.

During his talk, he presented the history of this information, and explained how Danish society benefits from it. Afterward, there was an interactive discussion on how the local community in Georgia can become more active in volunteering, and how to build trust so that future projects also involve those whom they affect. He said that, for him, the focus is meeting people face to face and including those in the decision-making process who will be influenced by the change.

“If you’re building a new hiking trail in the mountains, talk to people living in the villages there, ask for their advice and invite them to visit and take part in the trail work,” Dalsgaard tells GEORGIA TODAY. “It’s all about bringing together people who want the same kind of change, designing the best solutions together, and creating a community around the project.”

For the public, the event was a chance to learn about ecological issues, see solutions or starting points to solve them, and to show the complexity of life and nature. For the master students, it was an inspiration for the potential projects they could create.

The ‘Creative Mediation’ master’s program lasts three months and is project-based participation. Each person who enrolls is expected to research, develop, and implement a social and ecological project by the end of the program. Throughout the three months, all workshops and seminars are shown publicly through a presentation or exhibition for the general public to learn about the issues and findings.

Galaqtion Eristavi, CO of CCA, says the program is a way for people to find new roles and workplaces within society. He tells us that implementing something requires a large amount of effort from everyone involved, but through the master’s, students can see the work that needs to be done in an inspiring way. He adds that solving ecological issues creatively is not something that can be started and finished; it requires more behavior and reflection.

“Painting you can do, not moving from the chair, but creating new social structures needs movement. This is very visible here, of how complex and big they can be,” Eristavi says.

Tsereteli notes that artists always have to deal with the future, and they use this mindset to spread the word and raise awareness about climate change and ecological issues. He believes that artwork is the environment around people, and everything related to it. To Tsereteli, artists can use various modes of thinking, such as intellect, mistakes, accidents, imagination, etc., and combine or switch them to find alternative results to problems.

“Art is a scientific method of creative research,” Eristavi says.

Over 200 people have studied the master’s program since its launch in 2010. The New Democracy Fund supports the program, and the Goethe Institute supported the ‘From Me to We’ event. The program is designed differently each time, this year it started with a trip to Uplistsikhe and the three-day event. There will be more public events throughout the next three months to learn about ecological issues and awareness.

By Shelbi R. Ankiewicz