Much of the legacy of naval warfare is filled with the imagery of large, tall, wooden ships dueling with incredible volleys of ship-mounted cannon and musket fire, concluding with boarding and a clash of sword and spirit. These close range engagements are what made the legends of some of the world’s greatest naval leaders. John Paul Jones, Horatio Nelson, Chester Nimitz, and Karl Dönitz, to name a few, were undoubtable masters of the sea. Now, with new anti-ship missile (ASM) technology, the ship-on-ship combat seen during the times of these aforementioned heroes is something relegated to the past.

Much of Georgian modern naval supremacy in the Black Sea has been consigned to that of a dream. After the elimination of the Georgian Navy in the 2008 August War, the remaining vessels were reformed into a coastal patrol force. The Russian invasion in Crimea and a build-up of their Black Sea Fleet has only been lightly checked by NATO naval patrols coming through to conduct exercises with Turkey and Georgia.

Despite this assistance, it is glaringly imperative that Georgia take its naval defense and security seriously.

The Georgian Coast Guard, a branch of the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Border Police department, is charged with the defense of the nation’s shores. Sadly, this organization has the inglorious business of fending off any potential incursion. With their inadequate firepower and vessel numbers, this will most certainly be an effort in vain.

After decades of NATO and Georgian involvement in the Global War on Terrorism, much has been invested in ground combat. Fighting the enemy and their proxy forces in small villages and towns, destroying hostile armor, and scrambling electronic systems during the assault. The strength and will of the Georgian ground defense forces and accompanying popular militia may even halt or at least stall an overland invasion of the country.

However, in the near-future event of further Russian aggression or any other act of naval aggression, it is doubtful that the Coast Guard would be able to resist the onslaught of their Black Sea Fleet. The primary port of Sevastopol contains the core of their attack vessels, and, as of early 2021, this extensive force is compiled, though not exclusively, of:

• 1 guided missile cruiser (Moskva)

• 5 guided missile frigates (Admiral Grigorovich, Admiral Essen, Admiral Makarov, Pytlivy, Ladny)

• 11 missile corvettes (Grayvoron, Ingushetia, Orekhovo-Zuyevo, Vyshny Volochyok, Bora, Samum, R-60 Burya, R-109 Briz, R-334 Ivanovets, R-239 Naberezhnye Chelny, and the R-71 Shuya)

• 3 anti-submarine corvettes (Muromets, Suzdalets, Aleksandrovets)

• 1 diesel submarine (Alrosa, though she is slated to be transferred to the Russian Baltic Fleet)

• 6 minesweepers (Ivan Antonov, Vladimir Yemelyanov, Ivan Golubets, Vice Admiral Zhukov, Turbinist, Kovrovet)

• 6 intelligence collection ships (Ivan Khurs, Priazovye, Donuzlav, Stvor, Ekvator, Kildin)

• 3 amphibious transport docks (Nikolay Filchenkov, Saratov, Orsk)

• 4 naval landing ships (Novocherkassk, Azov, Caesar Kunikov, Yamal)

• 4 military cargo ships (Dvinitsa-50, Vologda-50, Kyzyl-60, Kazan-60)

This represents only the forces assigned to Sevastopol, and does not include the additional naval forces assigned to the regional port bases of Feodosia and Temryuk. The Novorossiysk naval base also provides another litany of naval assault and support forces, making the threat all too real for Georgian coastal defense units. To further complicate matters, the garrison of Russian S-400 missile batteries outside of the Crimean regional capitol city makes the Black Sea all that more of a potential flashpoint.

All of these combined factors highlight the pressing need for a coastal defense solution that is effective for both the military tasked with national defense and for the Georgian taxpayer. While the dreams of a new Georgian Navy may lie on the distant horizon in restored and updated American and European warships, the near-future solution lies in land-based defense. Coastal artillery batteries and anti-ship ordinance make quite the case in this realm.

Traditional coastal artillery in the form of large-bore guns housed in immense concrete bunkers are mostly relegated to the past. Modern penetrating munitions delivered by both naval and air platforms have overcome this once stalwart defense by rendering the reinforced concrete positions obsolete as well as prohibitively expensive. Georgia, looking at some of the naval tensions in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, can gain some valuable insight as well as technologies.

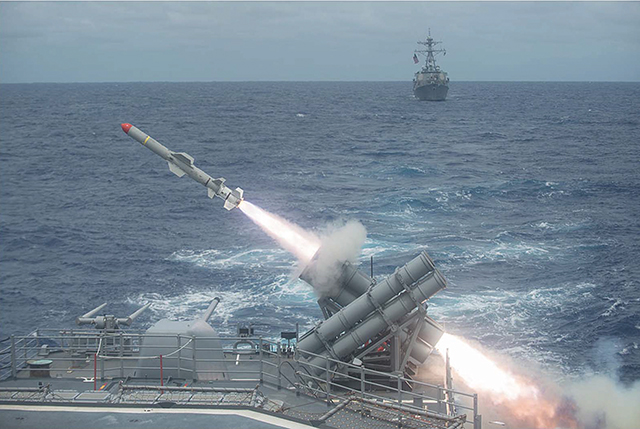

Several of the leading ASM systems used by NATO present themselves as ready and viable candidates for a new coastal artillery unit of the Georgian military. While there is a litany of solutions for land-based ASM systems, two of the most fitting for application in western Georgia are the RGM-84 Harpoon ASM and the EXOCET MM40 Block 3 Coastal Defense System. These systems, both in use with Georgia’s allied navies, offer a significant strategic littoral deterrent.

The Harpoon missile, named for its historical whale-hunting weapon system, is an older generation in the family tree of ASM platforms. Developed and later deployed during the 1970s, it became the fleet-wide ASM for both ship-mounted, aircraft-mounted, and land-based platforms. With more modern upgraded versions reaching out to almost 150 nautical miles (172.6 land miles), this platform has been in almost constant use around the world.

The EXOCET missile, manufactured by European defense firm MBDA missile systems, has made waves in the ASM field. With a significant operational history, particularly during the Falklands War against the British Royal Navy, these once had a home in the former Georgian Navy. The current version being used across the globe by over 30 navies and air forces has a maximum range of average 110 nautical miles (126.6 land miles).

These ASMs are “over the horizon” capable, meaning that these munitions are able to be delivered to long-range targets that would otherwise be unable to be engaged by traditional artillery or shoulder-fired weapons. This long engagement distance is coupled with their “sea skimming” flight technique. This technique involves the ASM flying between 2 to 50 meters above the surface of the water, evading the radar and defense systems of the target vessel. When approaching a target vessel at this low altitude, the target ship is often only given under one minute to respond to the threat once detected.

Both of these ASM systems are fully available for coastal batteries, and capable of being organized into the Georgian defense force framework. This implementation is a relatively simple undertaking given the typical complexity associated with the raising of new military units. In addition, the Georgian coast lends itself to a natural defense.

The curvature of the coastline and the strategic location of key cities makes the placement of coastal artillery ASM batteries easy. Each battery would be responsible for a particular sector of the Georgian littoral region. Batumi, Kobuleti, Poti, and Anaklia posts make the eastern Black Sea a “kill zone”, to use the tactical term, of overlapping fields of control.

At the battery level, each unit comprises four major components; The radar/sensor unit, the control unit, and 2 missile firing units. The radar/sensor unit is tasked with target acquisition and surveillance of the target area. The Control Unit is the overall command element for the combined unit, making firing commands, and managing and supervising the combined unit. The 2 missile firing units are the ASM components of the combined unit, responsible for upkeep and launching the ASMs. Each missile company has its own organic maintenance detachment for routine repairs and field troubleshooting.

Each combined unit is a vehicle-mounted and highly mobile coastal defense asset. Elements maintain 8 loaded and staged ASMs with resupply being handled at the battalion level to ensure ASMs are ready to be reinstalled. Together, these coastal ASM batteries ensure that any circumvention of the overland invasion route by way of the Black Sea would be a fatal decision.

Each battery at the aforementioned locations would be under the leadership of a captain or major, the NATO equivalent of an O-3 or O-4, while the ASM battalion would fall under the equivalent of an O-5, or Lieutenant Colonel. This headquarters would be stationed alongside the coast or as far inland as Kutaisi.

These command and control elements would be integrated into the force-wide Command, Control, Computers, Communication, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) digital framework. The data gathered from the radar/sensor units would allow command staff to anticipate any littoral threat and react with deliberate prevention and area denial tactics.

A project of this magnitude will surely find its detractors. The breadth, complexity, training and maintenance considerations, and the inevitable cost, will all require deep examination by the nation’s leaders and military experts. Contrarily, the opportunity to partner with European and American defense firms further links Georgia with NATO and Western spheres, a positive for all facets of Georgian statehood. All of these will need to be weighed with consideration of the security of the nation, the budget of the total defense framework, and the combined mission that stands against continued aggression and subversion by the Kremlin.

By Michael Godwin