Irina Gachechiladze’s chamber opera Eva premiered at the Tbilisi State Conservatoire, offering a contemporary take on the story of Eve. The production focuses on the psychological and emotional journey of a woman alone in Paradise, exploring themes of desire, freedom, and self-awareness. With music by Josef Bardanashvili and a libretto by Jemal Adjiashvili and Alexander Parin, the opera combines a small ensemble of musicians with a cast of six performers, creating an intimate setting where every movement, sound, and pause contributes to the narrative.

GEORGIA TODAY had the opportunity to sit down with Irina Gachechiladze to discuss Eva, learning about the creative choices behind the production, her approach to contemporary opera, her interpretation of the characters, and the ways in which she sought to bring this timeless story to life for a modern audience.

How did the idea to stage the opera Eva come to you?

Eva is part of my long-term project dedicated to the development of contemporary opera in Georgia. I am particularly drawn to chamber formats, which allow intimacy, psychological depth, and a close dialogue between music, performer, and audience.

This project has several aims: to support new voices in contemporary composition and libretto writing, and to create real opportunities for talented singers and musicians to participate in new opera productions. In today’s fast-paced world, people often feel they lack the time or emotional readiness for long traditional performances. Chamber opera, for me, is like a refined culinary experience, a concentrated, meaningful “bite” that leaves a strong aftertaste and food for thought.

I believe opera subjects must speak to contemporary audiences, especially younger generations who may feel disconnected from 19th-century narratives. If they fall in love with the operatic experience through modern themes and forms, they may later discover the classical repertoire as well.

How would you explain the main theme and message of this opera?

Eva is the inner journey of a woman through different stages of consciousness. It begins with longing and idealization, moves through loneliness, desire, and self-discovery, and ultimately reaches maturity and freedom.

In this version of the myth, Eva is in Paradise without Adam, alone with her thoughts and emotions. The Snake is not an external enemy, but a projection of her inner voice: temptation, doubt, curiosity, and courage. The true “sin” is not tasting the forbidden fruit, but daring to think, to choose, and to take responsibility.

Here, freedom itself becomes a punishable act. Eva fears divine punishment, yet she dares to leave Paradise and step into the unknown. This conflict between the comfort of obedience and the risk of freedom is profoundly human and deeply feminine.

The opera ends on a positive note. Eva reunites with her love, transformed by experience. The color of blood-red fruit reappears in her final costume. Experience is not discarded; it is worn. It becomes her strength and her beauty.

What was most important for you when shaping the character of Eva?

I deeply relate to Eva. I do not believe a director can truly stage a character without a personal connection.

Opera directing is a precise discipline: music comes first, then the libretto, then the performer. The director’s task is to unite all three so that the music can fully breathe through the singer.

Eva is presented as a fully human figure rather than an archetype. Her physical and emotional language was shaped around the natural plasticity and emotional intelligence of mezzo-soprano Irina

Sherazadishvili. Her body awareness, acting skills, and sensitivity allowed us to create a character that feels alive, vulnerable, and emotionally exact.

Eva needed to be complex, contradictory, fragile, rebellious, and strong at the same time. I wanted her to feel not like a mythological symbol but like a living woman experiencing fear, desire, tenderness, and transformation. Authenticity was essential.

How did you approach the interpretation of the Snake’s character?

For me, the Snake represents an inner voice rather than an external figure. This led to the decision to assign the role to a musician, the pianist, whose dialogue with Eva unfolds through sound rather than physical action.

Chamber opera is like a refined culinary experience, a concentrated, meaningful “bite” that leaves a strong aftertaste and food for thought

The Snake is not evil; it is a catalyst for awakening. It is a psychological whisper that challenges certainty and invites curiosity. It embodies both danger and truth, temptation and liberation.

Working with highly intelligent and sensitive musicians allowed this philosophical idea to emerge organically through music and stage action.

Could you tell us about your collaboration with Josef Bardanashvili?

I have known Josef Bardanashvili for over twenty-five years. We first met in Israel, where he had seen my earlier works, including my musical films shown at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque.

When I began developing my contemporary opera project, collaborating with him felt inevitable. He generously supported the idea and offered his compositions, from which we shaped this chamber opera.

Eva is built as a single narrative from three musical parts. The first and last are based on Jemal Adjiashvili’s poetic translations of ancient Jewish texts, while the central section, Eva’s dialogue with the Snake, uses a libretto by Alexander Parin. This text is philosophically bold, psychologically rich, and unafraid to address freedom, passion, and self-awareness.

Working with Bardanashvili means listening deeply to the music and allowing it to define the spatial and dramatic logic. His work contains emotional truth, a sense of humor, and spiritual resonance while offering remarkable freedom to directors and performers. It was a rare and beautiful collaboration.

How did the small-ensemble format influence your directing process?

A small ensemble creates intimacy and demands absolute precision. Every gesture, breath, pause, and silence becomes meaningful. Nothing can hide.

This format allowed me to focus on psychological detail, fragility of relationships, and the purity of vocal expression. That level of honesty is both demanding and artistically powerful.

Which scenographic details were most important for you?

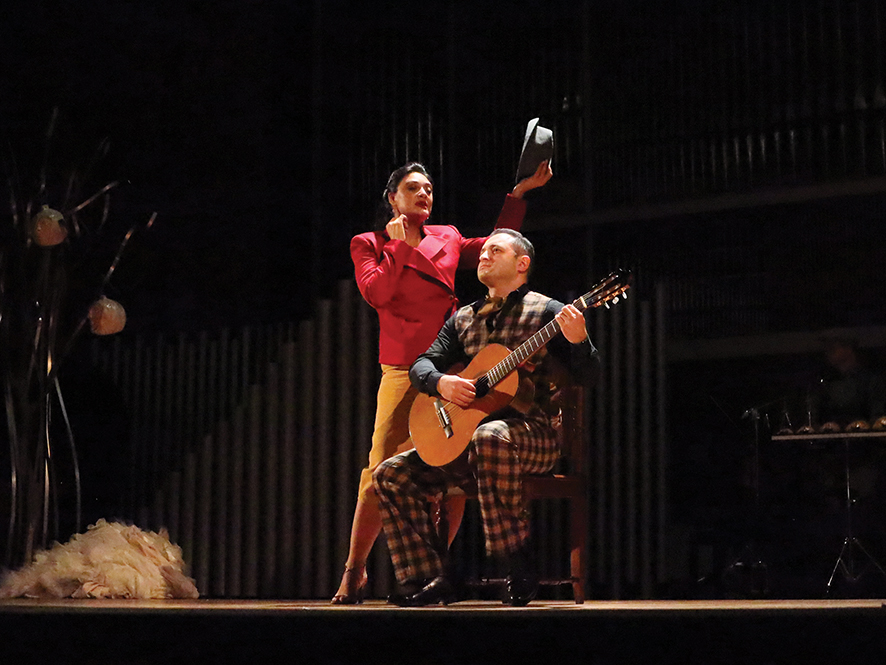

The venue, the Tbilisi State Conservatoire, played a decisive role in the scenography. Rather than neutralizing the space, I worked in dialogue with it. Wood, metal, and organ pipes became part of the visual language.

Since the opera depicts an inner transformation rather than external events, the space had to be symbolic and abstract, minimal yet emotionally charged. Deconstructed metallic structures echoed the organ pipes, expanding the architecture into a psychological landscape.

The forbidden fruits on the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil were given faces, so knowledge looks back at us. In the libretto, Eva speaks of tasting Adam’s flesh, and this unsettling imagery needed to exist visually as well.

I see scenography as a score for the eye. Texture, light, shadows, fabric, and spatial geometry carry as much meaning as words or music.

How do minimalism and symbolism balance in your staging?

Minimalism gives space for imagination, and symbolism gives depth. I seek the point where these two meet, a clean stage filled with metaphor and emotional resonance. Every element must have a clear purpose.

Costume transformations became emotional revelations, charting Eva’s journey from innocence to self-determination. Red, representing desire, memory, and experience, threaded through the production like a quiet heartbeat. Experience is never erased; it remains part of who we become.

What was the collaboration with the performers like, and what requirements did you set?

I asked the performers for openness, honesty, and precise emotional work. We explored the psychological motivation behind every gesture and musical phrase.

In this production, musicians were not accompanists; they became characters, forces, and symbols.

Opera brings together many languages: music, movement, space, psychology, and symbolism. The director is the only person who sees the entire landscape and unifies it into a living organism. Without strong directing, opera remains decorative; with it, opera becomes urgent, theatrical, and alive.

What challenges arose during the preparation process?

The main challenges were time and resources. Contemporary opera requires deep attention to detail, and in a small ensemble, every element must be exact. Balancing artistic ambition with practical limitations is always part of the process.

What does participating in the Contemporary Opera Development project mean to you?

It means taking responsibility for the cultural future of the country.

Contemporary opera is about relevance and risk. It gives society a mirror that reflects our current questions, tensions, and hopes. New works keep the entire artistic ecosystem alive, including composers, performers, designers, and writers, ensuring that opera remains a living art form rather than a museum piece.

What emotions are you experiencing as you look back at the premiere?

My work is complete. Now it belongs to the audience.

Interview by Kesaria Katcharava