Berlin art season this year took place amidst massive protests by local artists and art institutions against substantial reductions in state funding for the arts. In spite of all odds, the extraordinary profusion of exhibitions, performances, and art events during Berlin Art Week earlier in September was overwhelming and diverse. Within the current climate, characterized by multiple crises, the author of this article selected to review exhibitions that attempted to be subversive in their character and choice of artists, critically engaged with the challenges of today, and managed to bring to public attention voices of those who are mostly overheard.

Take, for example, Savvy Contemporary, which exhibited a carefully selected group of artists who analyzed the hardships of migrants living abroad, separated from their homes. Close to Home: Remittance Spaces Between Arrival and Return questioned, through the artistic positions, not only the notions of native land related to family bonds changing through various generations but also the complexities of global socio-economic relationships that underlie patterns of migration based on transfers of money, goods, and more. Isn’t “home” the place where one feels at home and welcome? And if one is an outcast in foreign lands, why does one still choose to leave home and live abroad? For many, it’s not even a question of choice, but a way of survival: e.g. working abroad in the “West” doing jobs that no one would like to do in order to send money home, thus saving relatives from starvation; escaping from dictatorial political regimes; saving money to build private houses back home; or just moving abroad to secure better futures for children. Here are a couple of artistic positions one can’t help mentioning:

The taste of homeland is probably something that no one can resist, irrespective of the time one spends abroad. By setting a mirrored table with double-ended spoons filled with delicious foods from her home country, Akshita Garud from India, in collaboration with fellow artist Avantika Khanna, created the atmosphere of joy commonly related to a festively decorated table, as opposed by the bitterness of the context of the whole setting. With every spoonful the visitors took, they were supposed to think of the complicated psychology of give and take associated with it all. Because for every piece of food you offer, you expect to receive something in return and vice versa. Probably and most likely not a food offering but money that one is expected to send home to support family and friends—remittance. Low-paid jobs that migrants have to take up abroad are mostly exhausting and degrading, working hours extremely long and living conditions inadequate. Yet the bitterness of it all could hardly poison the joy of a tasty, lavish meal provided for by remittance money.

It’s not only about the money one sends as remittance but the intricate ways migrants are induced to search for to get this money to the respective destinations. Yairan Montejo, also known as Cinco, in his mural presented as a comic strip, showed all the absurd obstacles that stand in the way, making the act itself of sending money home an almost heroic endeavor. In a witty way, with his characteristic humorous protagonists, the artist managed to convey a critical tableau of entangled human dependencies caused by the absurdities of bureaucratic blockades characterizing contemporary money transfer systems, as well as the unfair distribution of wealth in general.

Tra My Nguyen, on the other hand, chose to focus in her installation Hung the Moon Behind the Curtain on fabrics with patterns characteristic of mass-produced Vietnamese garments. The remarkable patterns on pieces of fabric let the eye wander, enjoying their beauty, yet creating a symbolic counterpoint to the exploitative character of global fashion industries as well as raising awareness about the social injustices in globalized societies. The fabrics, mounted on tall narrow aluminum structures, echoed the proportions of Vietnam’s “tube houses”—multi-story dwellings often built with remittance incomes. Appearing like romantic curtains on windows or thresholds dividing the inside from the outside, the fabrics emerged as architectural elements and expressions of emotional labor.

Speaking of architecture—perhaps the most spectacular contribution to the exhibition was by Van Bo Le-Mentzel, an architect born in Thailand and living in Berlin. His Artist Wallidency, a true masterpiece of austerity, efficient space management, and Buddhist self-discipline, was a two-story wooden dwelling in a movable wall occupying all in all 355 cm x 80 cm plus 300 cm in height. Originally a container for furniture, this movable wall was redesigned by the architect into a place of work and seclusion with basic amenities like a mini electric stove, toilet, table to work on, and a bed upstairs. A subversive critique on the decadence of the luxurious, vast apartments and homes filled with a profusion of extravagant furniture trending among the rich upper classes of Western societies. Van Bo Le-Mentzel’s inspiration came from the life of Co Hanh Ngo, a Buddhist nun who used to live in a tiny room in a pagoda in Hanover. As an architect, he was fascinated by how she created a life for herself within just 5 square meters. Throughout her life, she remained active in a Buddhist community, sold souvenirs at fairs and in the pagoda gift shop. With the money she saved and sent to her daughter in Laos, she provided prosperity for her family back home: a two-story villa where her daughter set up a prayer room to remember her mother—ironically, very much like a conventional “home sweet home.”

A genuine highlight among the current Berlin exhibitions is undoubtedly Andrea Fraser’s work show at Nagel Draxler Gallery. Andrea Fraser has spent her artistic career interrogating the intricate power structures and emotional economies of the art world, and few works exemplify this as incisively as her iconic performance series May I Help You? (1991), the six recordings of which are now on view at the Nagel Draxler Kabinett, and her controversial project Untitled (2003).

In May I Help You? Fraser (and subsequently in further versions, invited performers) assumes multiple roles, each exposing a different perspective within the gallery ecosystem. The artist moves fluently between the voice of a highly skilled gallerist seducing collectors with persuasive rhetoric, an outsider excluded from elite cultural circles, and a passionate art lover whose devotion transcends market logic. Through these shifts, Fraser uncovers the language games and coded behaviors that sustain art’s economic and symbolic value. The work does not simply satirize the system; it reveals how deeply identity, desire, and power are woven into the seemingly neutral act of “selling” or “appreciating” art.

In Untitled (2003), Fraser extends this critical inquiry to its most intimate and unsettling terrain. The project documents a real transaction: a collector purchased the first edition of a video documenting his sexual encounter with the artist, staged in a gallery. The work does not sensationalize the act itself but contextualizes it through press releases, installation views, and historical references, exposing the centuries-old analogy between the sale of art and prostitution. Fraser insists that the collector paid for the artwork, not for the sex—an important distinction that lays bare the complex entanglement of desire, money, and power.

Across these works, Fraser poses a fundamental question: who defines what counts as art—and for whom? By exposing how cultural value is constructed and controlled, she reveals art’s double role as both a powerful instrument of exclusion and a potential shared space of common culture. Her practice compels institutions, collectors, and audiences alike to confront their own complicity in sustaining these structures, turning the mirror of critique directly toward the cultural sphere itself.

Last but not least, for the first time in decades, a Georgian artist, David Apakidze, has been featured by the Berlin Art Week 2025 as this year’s Kunstverein Ost grant holder and recipient of the 2025 Claus Michaletz Prize. In his exhibition The Knight at the Crossroads, a young queer artist from Georgia weaves a subtle yet powerful political narrative, confronting the persecution and repression that queer communities continue to face in his homeland—often with exile as the only escape. At the heart of his work lies the crossroads: a metaphorical state of uncertainty, of standing before multiple paths when facing systemic injustice.

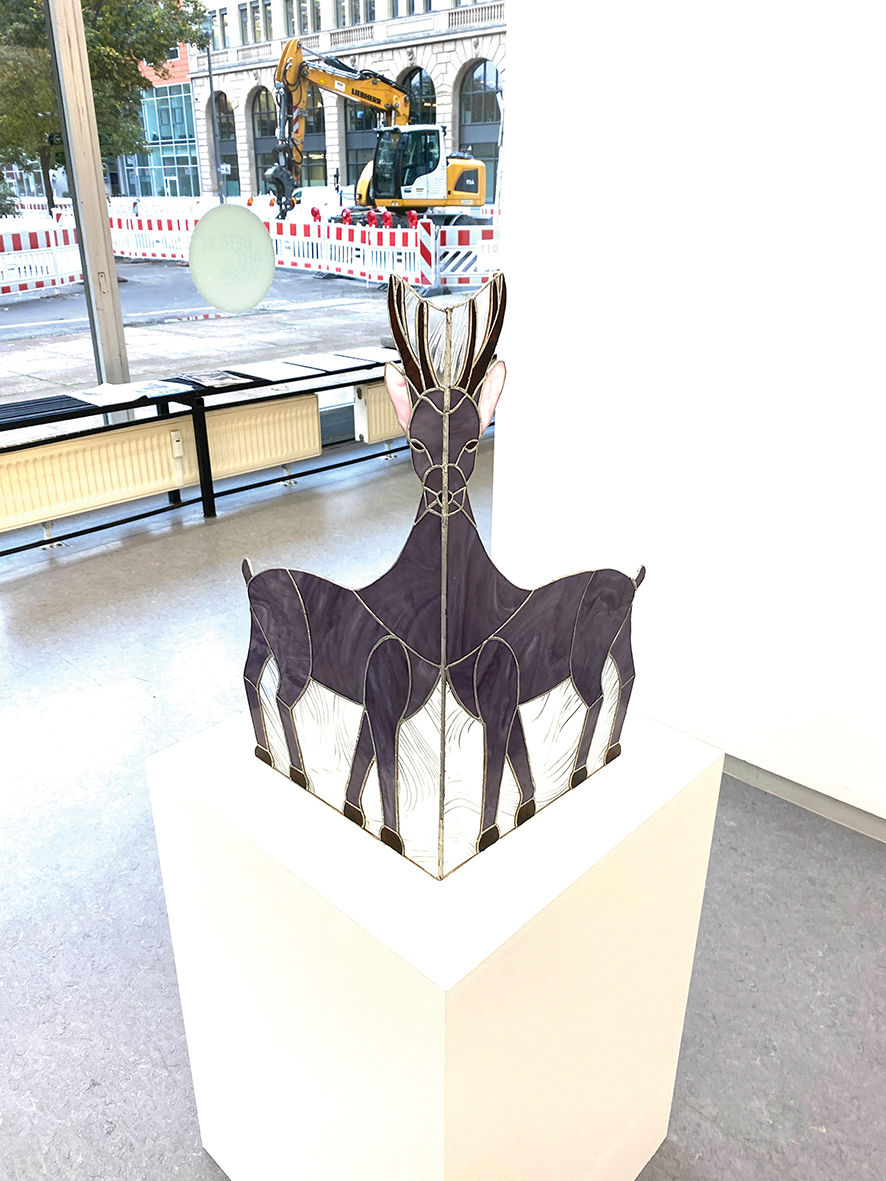

Through poetic stained-glass pieces, rendered in delicate colors and infused with visual references to instantly recognizable Georgian cultural imagery—knighthood, phallic daggers, and blood stains—the artist delivers a tongue-in-cheek yet sharply critical message. He exposes the violent and exclusionary undercurrents embedded in conventional interpretations of national symbols, revealing how these once-celebrated icons are blood-stained relics of power.

By recontextualizing these cultural motifs through a queer lens, the artist opens a space for their reinterpretation, questioning what national identity can mean today. His work does not seek to erase tradition but to transform it, showing how shifting perspectives can make cultural heritage relevant to contemporary societies—more open, inclusive, and capable of embracing difference.

By Dr. Lily Fürstenow-Khositashvili