The Tbilisi International Festival of Theater chose to open its international program with Shakespeare’s Richard III, and this decision already reads as an editorial gesture. In a city where theater has historically operated as a barometer of social upheaval—whether during the Soviet period or the ongoing struggles of a fragile democracy—the arrival of Tel Aviv’s Gesher theater with Itay Tiran’s furious, unsparing production feels both timely and incendiary. It signals that the festival is not content to offer cultural diplomacy or polite classics. Instead, it begins with a provocation: a work that dares to connect Shakespeare’s late-medieval nightmare with the present tense of political life.

Richard as a Symptom of Family, Nation, and State

“Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” Tolstoy remarked, and Richard III embodies that observation with terrifying precision. Shakespeare’s play begins as a family feud, proceeds as a dynastic tragedy, and culminates in a national collapse. Gesher’s staging pushes this genealogy of destruction further, suggesting that in the twenty-first century the personal rot of one household metastasizes into the corruption of entire states. Richard is not just a figure of ruthless ambition; he is the malignant growth produced by alienation, humiliation, and a society too willing to accommodate cruelty.

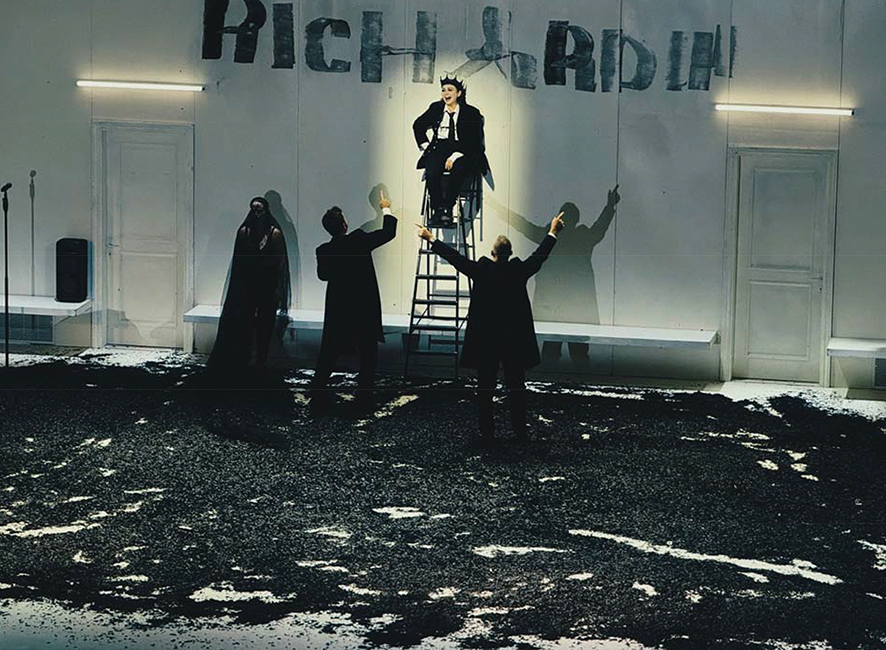

Evgenia Dodina, cast against type as Richard, embodies this idea to staggering effect. Her performance is at once grotesque and magnetic, a study in theatrical paradox: fragility laced with menace, charm curdled into sadism. By embodying the role as a woman, Dodina fractures centuries of expectation, pulling the character into a new register. This Richard is no longer simply the archetype of masculine tyranny but an unstable amalgam of gender, power, and deformity. The audience sees not only a villain but a theatrical chimera—part Joker, part Hamlet, part authoritarian demagogue.

The Black-and-White World of Itay Tiran

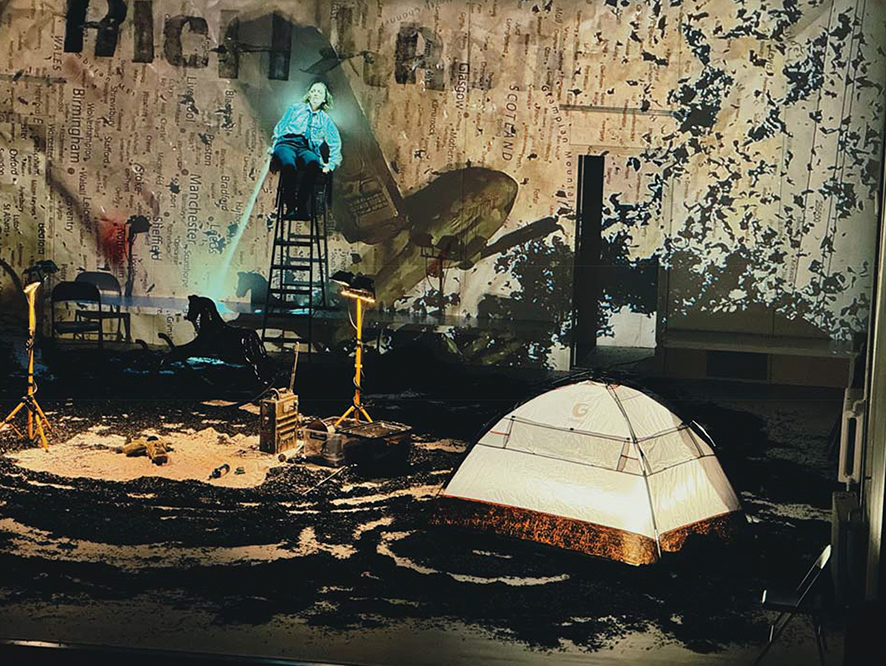

If Dodina carries the psychological weight, Tiran’s direction establishes the visual and symbolic grammar. The stage becomes an arena where moral binaries suffocate nuance: black and white dominate every costume and backdrop, evoking film noir and erasing individuality. This design choice—Eran Atzmon’s set, Gleb Filshtinsky’s lighting—presses the audience into an environment of perpetual moral starkness. A rain of ash accumulates across the stage, an environmental metaphor for decay that is at once subtle and relentless.

The coronation scene crystallizes Tiran’s dramaturgical logic. The throne is not a seat but a black chair suspended absurdly high, accessible only by ladder. The visual allegory is ruthless: power is an abstraction, always beyond reach, yet pursued with blood-soaked zeal. What is worshipped here is not kingship, but the fetish of power itself—empty, elevated, and absurd.

Israeli Echoes, Georgian Resonance

One of the production’s most daring gestures lies in its incorporation of classic Israeli songs. Their sudden eruption interrupts Shakespeare’s language with fragments of contemporary cultural memory, forcing the audience to read Richard not as a medieval tyrant, but as a perennial type haunting modern politics. An insistence that tyranny is never far away, that each society—Israel’s, Georgia’s, or anyone’s—is a few steps away from its own Richard.

This dramaturgical choice takes on layered meaning in Tbilisi. Georgia has repeatedly experienced how familial fractures in ruling elites translate into state fragility, how private vendettas erupt into public ruin. Gesher’s Richard III thus refracts through the Georgian audience like a dark mirror, inviting spectators to read Shakespeare’s text as both foreign and uncomfortably intimate.

Richard as Archetype for Our Times

The brilliance of Gesher’s production lies in its refusal to domesticate Shakespeare. Richard remains excessive, grotesque, and almost unbelievable. But in that excess, he becomes recognizable as the distorted reflection of our own world: the serial killer who governs like a CEO, the demagogue whose charisma is inseparable from cruelty, the manipulator who thrives in the absence of shared values.

By opening its international program with this production, the Tbilisi International Festival of Theater declares itself a space where theater can perform its most ancient role: as a civic mirror, exposing the contradictions of its society. Gesher’s Richard III insists that tyranny is never an artifact of history but an ongoing possibility, lurking whenever communities confuse stability with submission, or allow violence to masquerade as order.

As the ash settles on stage and the suspended chair hovers above an empty kingdom, one understands why this production inaugurates the festival’s international offerings. It is theater as dark prophecy, theater that does not console but unsettles, theater that dares to place Georgia’s current anxieties within Shakespeare’s brutal dramaturgy. To begin with Richard III is to begin with a warning. And warnings, in Tbilisi, are rarely ignored.

Review by Ivan Nechaev