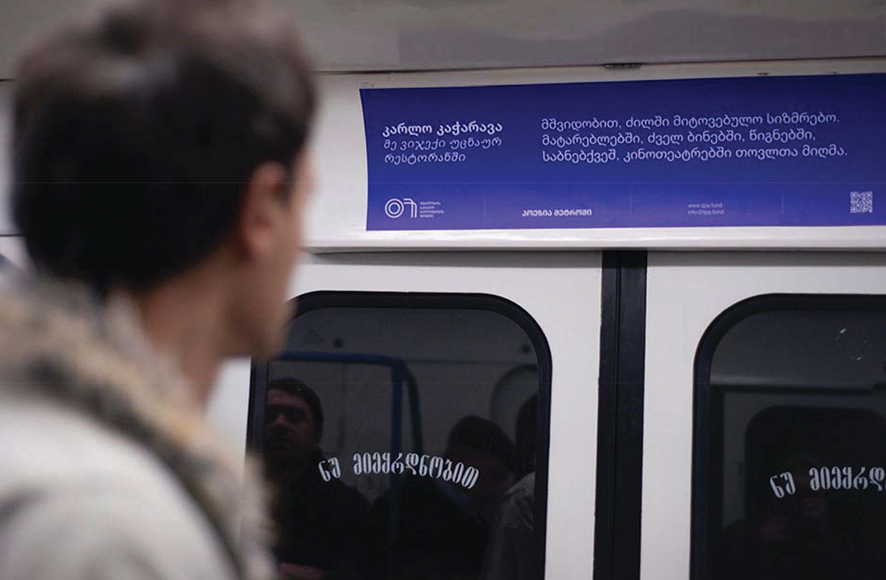

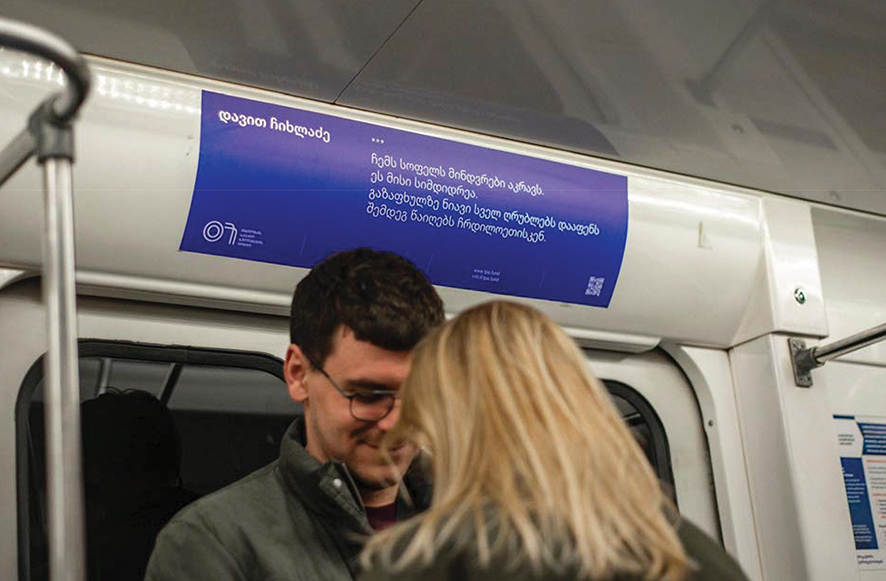

Where a detergent ad or a telecom slogan would normally glow above the window, a stanza appears instead. A fragment. A line broken in mid-thought. A voice from the 1990s, resurrected between Didube and Rustaveli. The project is called “Poetry in Motion: Traveler’s Angel,” and it marks a new direction initiated by the Tbilisi Public Art Foundation in collaboration with the poet and musician Erekle Deisadze.

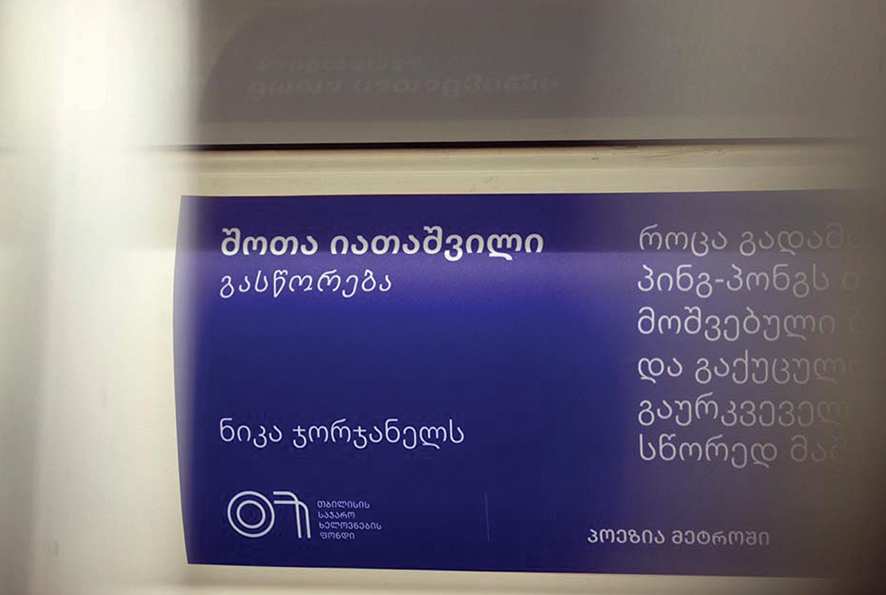

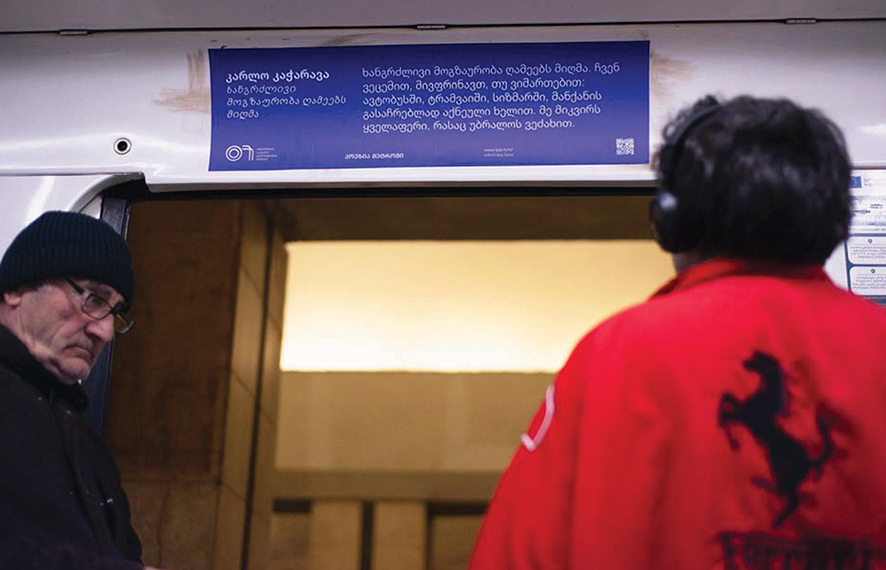

From January 30 to April 30, excerpts from three major figures of late-twentieth-century Georgian literature—Karlo Kacharava, David Chikhladze, and Shota Iatashvili—occupy the advertising spaces inside metro wagons. The daily commute becomes a temporary literary field.

The 1990s as an Unfinished Conversation

To revisit Georgian poetry of the 1990s is to reopen a decade still vibrating beneath the surface of the present. The collapse of the Soviet Union produced rupture and improvisation in equal measure. Infrastructure failed; aesthetics mutated. The literary language of the period absorbed instability as texture.

Deisadze’s curatorial gesture is precise. He frames these three authors as “children of the same epoch” who shaped the poetic landscape through distinct formal strategies and voices. With distance, he suggests, their work acquires cultural legitimacy that was once contested or precarious.

Karlo Kacharava, painter and theorist as much as poet, belonged to the generation that radically reconfigured Georgian visual and textual thought in the 1980s and early 1990s. A founding member of the self-organized groups Archivarius and later The Tenth Floor, he operated at the intersection of art history, painting, and literature. His intellectual rigor was sharpened by study at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts and by exposure to Western curatorial practices in Cologne in 1991. His early death in 1994, at thirty, fixed him in cultural memory as both avant-garde catalyst and unfinished project. Today his works reside in major collections including TATE Modern and S.M.A.K. in Ghent—a trajectory that mirrors the belated international recognition of his circle.

David Chikhladze emerged slightly earlier, publishing poetry and criticism from 1981 onward. A poet and theater director, founder of Tbilisi’s first independent “Alternative Art Gallery” in 1989, and later active in New York’s experimental theatre scene, including collaborations around Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater, Chikhladze extended Georgian poetic sensibility into transnational performance contexts. His anthologized presence in the United States, Austria, Norway, and beyond marked one of the earliest sustained outward movements of Georgian avant-garde literature after Soviet isolation.

Shota Iatashvili, poet, prose writer, critic, and translator, represents another vector of continuity. With more than ten poetry collections, multiple novels, and international awards including the SABA Prize and recognitions in Ukraine, Poland, Slovenia, and Bulgaria, he embodies the institutional stabilization of post-Soviet Georgian literature. His texts circulate in over twenty-five languages. The once-fractured literary field now speaks globally.

Replacing Advertising with Memory

The conceptual strength of the project lies in its spatial intervention. Commercial advertising structures perception in transit spaces. It commands attention through urgency and repetition. Poetry, installed in that same format, adopts the infrastructure while altering its rhythm.

A metro carriage is an intimate public sphere. Bodies are close; eyes wander; attention drifts. In that drifting, a line of verse may enter more quietly than in a bookstore or gallery. It shares space with fatigue, headphones, private anxieties, phone screens. The poem becomes incidental and therefore strangely personal.

The Tbilisi Public Art Foundation frames the initiative as a dialogue between past and present, between personal and collective memory. The claim risks sounding rhetorical until one stands inside the wagon. There, the metaphor clarifies: the 1990s were years when public infrastructure nearly collapsed. Today, that infrastructure carries stabilized fragments of the era’s inner speech.

The project also grows from the Foundation’s educational program. Deisadze’s earlier lecture series, “Rereading,” introduced twentieth-century Georgian poets to high-school students across Tbilisi, proposing alternative readings of the standard curriculum. The metro installation extends that pedagogical impulse outward. The classroom dissolves into the city.

The Curator as Contested Figure

Erekle Deisadze himself remains a complex cultural actor. His 2010 debut book generated sharp public debate for its explicit engagement with political and religious themes. As a musician, first with “Parallel Generation,” later with the punk band “40 Kilometers Away,” and through experimental collaborations such as Eko & Vinda Folio, he cultivated an aesthetic of confrontation and directness.

In “Traveler’s Angel,” the tone shifts. The gesture is archival, reflective, almost tender. Rather than foregrounding his own polemical voice, Deisadze curates a lineage. The move suggests maturation without erasure. It also demonstrates how figures once defined by provocation can assume the role of mediator between generations.

Poetry in Transit

There is something quietly radical about encountering Karlo Kacharava above a plastic seat, or Shota Iatashvili where a bank advertisement once demanded credit. The metro does not transform into a temple of high culture. It remains loud, functional, impatient. That friction is the point.

Public art often oscillates between spectacle and invisibility. This project chooses the second mode. It relies on accident: a commuter looking up, a sentence lingering after arrival. The poem travels the line repeatedly, accumulating readers without ceremony.

In a city negotiating its past and its velocity, “Poetry in Motion” proposes a modest recalibration of attention. It offers literature without ticket price, without gatekeeping, without framing glass. It trusts that a fragment from the 1990s can still converse with the present tense of Tbilisi. Somewhere between stations, a passenger reads a line written three decades ago. The train moves. The text remains.

By Ivan Nechaev