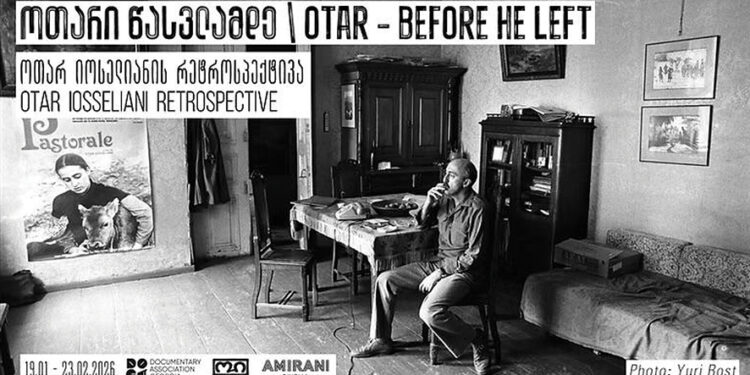

When DOCA Film Club launches a retrospective, the gesture rarely functions as a commemorative ritual. Over the years, DOCA has shaped its audience into readers of programs rather than consumers of schedules. A retrospective, in this context, becomes a curatorial essay written in screenings, pauses, and carefully chosen intervals. Otar – Before He Left, unfolding across January and February at Amirani Cinema, belongs precisely to this tradition: a long-form meditation on cinema as a practice of attention.

The figure at the center, Otar Iosseliani, has always resisted neat positioning. His films circulate freely between documentary and fiction, music and labor, comedy and melancholy, urban noise and rural stillness. Watching them in chronological proximity reveals something essential: this is cinema built on duration rather than plot, ethics rather than thesis, gesture rather than statement.

January: The Grammar Is Already There

The retrospective opened on 19 January with a cluster of early works that function as a quiet manifesto. Aquarelle and Sapovnela (1959), followed by April (1962) and Cast Iron (1964), establish a vocabulary that will persist for decades. Dialogue is absent. Meaning arises from rhythm, from the placement of bodies in space, from the insistence that everyday objects deserve as much cinematic respect as human faces.

In Aquarelle, Iosseliani’s graduation film, irony appears without punchlines. Actions unfold with a musical sense of timing, suggesting that cinema, for him, is already closer to composition than narration. Sapovnela deepens this intuition, treating sound, color, and movement as elements of a single score. The world hums, clinks, rustles.

April sharpens observation into social critique without relying on explicit commentary. Love drifts out of focus amid accumulating objects, furniture, routines. The film’s history with Soviet censorship is well known, yet its enduring power lies elsewhere: in the calm with which it allows material life to reorganize emotional priorities. Cast Iron, the documentary portrait of the Rustavi Metallurgical Plant, extends this logic into industrial space. Labor becomes tempo. Fatigue becomes visible. The factory breathes alongside the workers.

Late January: Ethics Without Elevation

On 26 January, Falling Leaves (1966) occupies the evening, accompanied by Film Journal 2–3 (1967), a commissioned chronicle for the anniversary of the Tbilisi Conservatoire. The pairing is instructive. Falling Leaves follows a young man whose quiet insistence on professional integrity isolates him within a collective system built on compromise. The film’s moral tension unfolds without dramatic escalation. Decisions register through posture, silence, repetition.

Film Journal 2–3, by contrast, presents an official celebration, polished and ceremonial. Seen alongside Falling Leaves, it reads as an accidental essay on public ritual and private conscience. Iosseliani’s cinema never shouts its conclusions; it allows adjacency to do the work.

February: Cities, Songs, Countryside, Return

The February screenings widen the lens. On 2 February, Georgian Ancient Songs (1968) precedes There Once Was a Singing Blackbird (1971). Folk polyphony emerges within everyday contexts—feasts, labor, coexistence—untreated as heritage display. Song circulates as social glue. The feature that follows shifts to urban Tbilisi, where the city itself becomes an acoustic environment. Street sounds, rehearsals, missed cues, chance encounters assemble a portrait of a man whose internal rhythm never aligns with institutional time. Comedy drifts gently into melancholy. Life continues.

Pastorale (1976), screened on 9 February, stands as one of Iosseliani’s most intricate constructions. Musicians retreat to the countryside, where rehearsals, meals, work, and nature form a deceptively calm surface. Underneath, incompatibilities accumulate. Art, labor, and social organization share space without resolving their frictions. The countryside functions neither as refuge nor as idyll; it becomes another field of observation, governed by the same quiet ironies as the city.

The retrospective concludes on 16 and 23 February with Alone, Georgia (1994), shown across its parts. Made during Iosseliani’s temporary return for Arte, the film avoids the familiar grammar of national portraiture. There is no explanatory arc, no touristic impulse. The country appears fragmentary, discontinuous, observed with a gaze sharpened by distance. Nostalgia surfaces briefly, then recedes. Skepticism lingers longer. Affection survives without sentimentality.

A Cinema That Trains the Eye

All screenings in the program are presented with English subtitles, an important curatorial choice that extends the conversation beyond linguistic borders. Yet accessibility here does not translate into simplification. Iosseliani’s cinema demands a particular mode of viewing—patient, alert, receptive to minor variations. Meaning emerges cumulatively, often sideways.

What DOCA Film Club constructs through this retrospective resembles a long sentence rather than a series of statements. Films respond to one another across decades. Early shorts converse with late documentaries. Industrial noise echoes in polyphonic song. Ethical solitude reappears in different guises. Georgia remains present throughout, less as a symbol than as a lived texture.

This is cinema that trusts the intelligence of duration. It understands that watching, sustained over time, reshapes perception. Otar – Before He Left offers precisely this experience: a space where film becomes a method of thinking, and thinking unfolds through looking.

By Ivan Nechaev