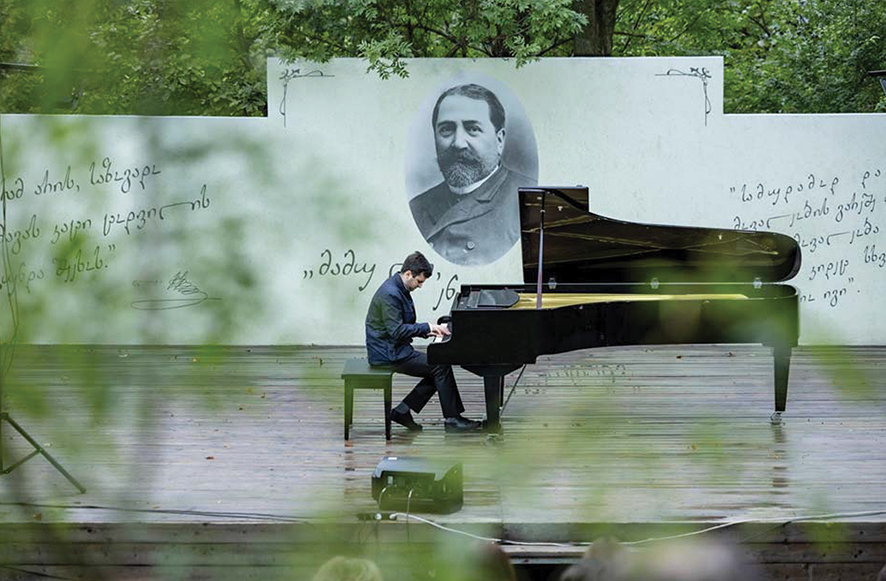

In Georgia, festivals often bear the weight of cultural survival. They are never only about the notes performed or the names in the program; they are, instead, moments of civic ritual, reminders that art can still create a shared horizon of meaning. The X International Chamber Music Festival in Saguramo, held in the gardens of the Ilia Chavchavadze State Museum, unfolded precisely in this key. Nestled among the memory-laden walls of the house-museum of Georgia’s 19th-century intellectual giant, the event celebrated not simply chamber music but the persistence of cultural intimacy in an increasingly fractured public sphere.

Saguramo is not Salzburg. There are no postcard Alpine backdrops or aristocratic patronages polished over centuries. Instead, there is the shadow of Ilia Chavchavadze—the writer, political thinker, and martyr of the Georgian nation—whose home, now a museum, frames the festival as both an aesthetic and ethical gesture. To stage music here is to stage memory, to turn a domestic garden into a civic agora. That transformation is itself an argument: chamber music as an antidote to political cynicism, a practice of collective attention.

The anniversary—ten years of the Camerata—was marked with the modest grandeur of three evenings, each drawing together performers from Germany, Italy, Belgium, and Georgia. The very multinational weave of the program suggested that chamber music retains a diplomatic force, one that resists the language of treaties and instead relies on counterpoint, timbre, and silence.

The second evening, September 20, belonged, at least in its first half, to the FM Quartett from Germany. Their program was both expected and gently provocative: Wagner and Mozart alongside the operatic fervor of Nessun Dorma and even a sequence of familiar songs. In the compressed architecture of a quartet, Wagner’s motifs shed their usual Teutonic density and became something else: translucent, chamber-scaled contemplations rather than monuments. Mozart, conversely, gained a darker intensity, as if refracted through the historical consciousness Wagner always brings into the room.

The inclusion of Nessun Dorma—a tenor aria transposed into the texture of four instruments—was less a populist bow than a small philosophical experiment. Puccini’s anthem of masculine triumph became, in the absence of words, a fragile meditation on the very idea of voice. Without the swelling operatic body, one heard the skeleton of the aria, its contour, its pleading arc. It was, paradoxically, both more universal and more ghostly.

If the Germans brought density, the Italians brought light. The Vivacidade Duo, blending Brazilian rhythmic verve with the architecture of Piazzolla, carved an entirely different affective space. Where Wagner had brooded, they danced; where Mozart had sculpted form, they improvised with color. Brazilian choro rhythms, slipping into Piazzolla’s tango-inflected melancholy, generated an atmosphere of fluid cosmopolitanism.

This was not the superficial exoticism of “world music” but rather a deliberate staging of dialogue: Latin America’s urban soundscapes meeting Europe’s classical canon on Georgian soil. The result was a kind of triangular conversation—Saguramo as mediator between Leipzig, Buenos Aires, and Rio de Janeiro.

The festival’s true innovation lay in its use of space. The main stage framed the larger concerts, yet the veranda of the house was transformed into an intimate hall, a threshold between domestic interior and public performance. This interplay between garden and architecture allowed the festival to become almost site-specific, a choreography of listening across multiple dimensions of the estate.

Yet certain weaknesses undercut this brilliance. The overabundance of spoken introductions and commentary often competed with the music itself, threatening to turn performance into mere background to narration. The festival also missed a rare chance to tie its audience more deeply to the history of the museum itself: the intermissions passed without guided walks or access to the exhibits that could have woven Georgian intellectual history into the listening experience. Music in Ilia’s house should have opened the door to Ilia’s legacy.

On the logistical level, ticketing and seating management felt underdeveloped. Audiences wandered into spaces without clear guidance, yet this very disarray inadvertently created a curious intimacy: listeners began to feel like insiders, almost family, a self-organized community rather than a regimented crowd. In a paradoxical way, the lack of control generated a new form of hospitality.

The significance of such programming in this place cannot be overstated. Ilia Chavchavadze, the host in absentia, believed in literature and art as engines of civic renewal. His museum garden, once a private domestic space, becomes under the weight of the festival a site of public pedagogy. The Ministry of Culture, Mtskheta Municipality, and local cultural centers appear as supporters, but the deeper patron here is Ilia himself, whose ghostly authority lends the festival both gravitas and a sense of continuity.

The Saguramo Camerata, once known as “Salkhino’s Camera,” has, in its ten-year trajectory, carved out precisely this dual function: to be at once an artistic platform and a civic ritual. It offers chamber music as a model of society itself: multiple voices negotiating, listening, sometimes clashing, always oriented toward fragile harmony.

What does it mean to celebrate ten years? For a festival in Georgia, survival itself is an achievement.

Political instability, economic precarity, and cultural marginalization often make such projects ephemeral. Saguramo’s persistence suggests something more than stubbornness; it signals a quiet demand for continuity.

The festival’s first year in this new location carried the inevitable imperfections of transition—overbearing hosts, underdeveloped logistics, a missed chance to bind music to history. But these are correctable flaws. What remains essential is the vision: to turn a garden into an agora, a veranda into a concert hall, and a museum into a civic forum where art, memory, and community entwine.

If Wagner in the garden could sound intimate, if Piazzolla could shimmer under Georgian twilight, then the festival has proved its point: chamber music can be both local and transnational, rooted and borderless, civic and sensual. In an age when music festivals too easily collapse into spectacle or tourism, Saguramo insists on a slower, more attentive form of listening.

Perhaps that is the truest anniversary gift: not only to celebrate music, but to remind us that listening itself is a civic virtue.

Review by Ivan Nechaev