In April 2025, the National Bank of Georgia published a quietly seismic statistic: foreign nationals now hold over 9.3 billion Georgian lari in local bank deposits—28.5% of all personal savings in the country. This number, up 18% from last year, is more than financial trivia. It is a mirror reflecting a deeper, often disquieting story of modern citizenship, displacement, and geopolitical flux.

Most strikingly, Russian citizens account for 3.44 billion lari, or 37% of all foreign-held deposits. They are followed by Israeli citizens (1.02 billion) and Ukrainians (558 million). Together, this trinity of geopolitical unease outlines a map of modern mobility—one drawn not by airline routes or real estate purchases, but by the quieter, more telling geography of savings accounts.

Why are so many non-Georgians storing their wealth in Georgia? And why these countries?

To answer this, we must look beyond economics—to history, sociology, and the long philosophical shadow of what it means to “trust” a state.

The Geography of Trust: Why Money Crosses Borders Before People Do

At its core, a deposit is a vote of confidence. It is a choice to entrust a legal system, a financial institution, and a national currency with the future. But deposits are also defensive acts—hedges against political instability, currency volatility, and even state surveillance.

Sociologist Niklas Luhmann wrote that trust is a mechanism for reducing social complexity. When a Russian tech entrepreneur or an Israeli businessman deposits funds in Tbilisi, they are simplifying a chaotic world into a manageable future. Georgia, for them, is not just a neighbor—it is an infrastructure of hope.

Russia: The Empire’s Shadow in Microfinance

The Russian capital surge is not an accident. It is a direct consequence of sanctions, capital controls, and a creeping authoritarianism, under which domestic financial freedom has become fragile. As with other autocratic regimes—from Francoist Spain to late Soviet stagnation—capital flight becomes both symptom and symbol of elite discontent.

According to historian Adam Tooze, in times of geopolitical isolation, the elite protect themselves by externalizing risk. In the Soviet era, this was done through offshore accounts in Switzerland or Cyprus. In post-2022 Russia, the geography has shifted. Georgia—with its visa-free access, euro-pegged currency regime, and relatively liberal banking laws—has become a new node in this ancient web of avoidance and preservation.

Israel: Diasporic Wealth, Historical Memory

Israel’s prominence as the second-largest depositor nation is particularly intriguing. While the country enjoys economic stability, it is also deeply shaped by a diasporic consciousness—a culture of contingency, historical trauma, and readiness for exile.

In 2023 and 2024, as Israel experienced mass protests against judicial reforms, many upper-middle-class professionals began seeking “Plan B” options—dual citizenships, foreign properties, and yes, foreign bank accounts. Georgia, with its historic Jewish communities and proximity to Europe, offered a stable and familiar ground. As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai would note, finance becomes a form of imagined migration—a symbolic act that prefigures physical departure.

Ukraine: Deposits as Displacement

Unlike the other top depositors, Ukrainian savers are often forced rather than voluntary participants in this trend. The ongoing war with Russia has displaced millions, and Georgia has become a relative haven—culturally familiar, economically open, and geographically close.

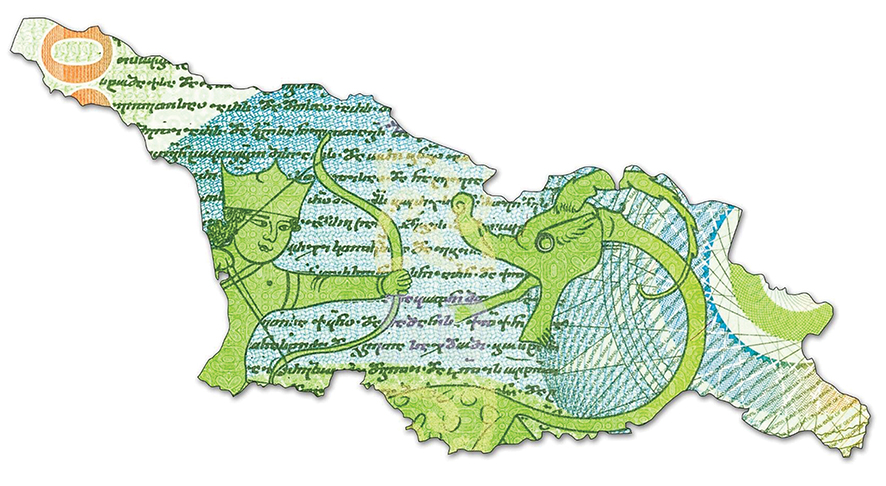

Foreign nationals hold over 9.3 bln Georgian lari in local bank deposits—28.5% of all personal savings in the country

Yet these deposits are not only signs of trauma. They are acts of reconstruction. For many, savings in Georgian banks are the beginning of a second life—a way to anchor oneself in a region that feels both near and safe. They echo the practices of other refugee diasporas throughout history: from Armenians in Aleppo to Iranians in Los Angeles, financial adaptation has always preceded political belonging.

Post-Soviet Continuums and Offshoring Echoes

Further down the list, the presence of Belarus, Azerbaijan, and British Virgin Islands reveals two other patterns.

First is the post-Soviet continuum: nations whose elites often share the same risk calculus, shaped by volatile regimes and opaque legal systems. Banking in Georgia allows these elites to “relocalize” their assets in a relatively Western-aligned legal environment, without fully entering the EU regulatory sphere.

Second is the offshore logic: countries like the British Virgin Islands or Malaysia appear in Georgian banking statistics not because their citizens are flooding Tbilisi’s streets, but because their corporate proxies are. In many cases, these are shell companies used by regional oligarchs to repackage domestic wealth into foreign-looking structures. Georgia, for now, offers the ideal midpoint between transparency and discretion.

Georgia: A Nation Becoming a Vault

The more Georgia attracts foreign deposits, the more it transforms—from a post-Soviet state with soft power dreams to a de facto safe haven in a region riddled with uncertainty.

At a time when traditional citizenship fails to protect, financial positioning becomes an existential strategy

This isn’t unprecedented. In the interwar period, Switzerland became a financial sanctuary not simply because of neutrality, but because of its perceived reliability—legally, bureaucratically, and culturally. Georgia is now poised for a similar role in the post-global, fragmenting world. But there are risks.

As political theorist Wendy Brown has argued, when nations begin to serve primarily as platforms for capital, their democratic institutions often suffer. A country whose infrastructure is shaped more by deposits than debates, by interest rates than public interest, may find its sovereignty subtly hollowed.

Saving for the End of the World

These 9.3 billion lari are more than a statistic. They are a collective whisper: a region’s unspoken fears, ambitions, and exits encoded in balance sheets and bank portals.

At a time when traditional citizenship fails to protect, financial positioning becomes an existential strategy. To save in Georgia is, in many ways, to gamble on the idea that smallness can be safety, that proximity can be power, and that neutrality, in an age of polarization, is worth a premium.

And so the vaults in Tbilisi fill—quietly, steadily—echoing not with the sound of money, but with the unending murmur of those who no longer trust their homelands to hold their futures.

By Ivan Nechaev